1. Overview

Bahrain, officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, is an island nation in West Asia, situated on the Persian Gulf. Comprising an archipelago of 50 natural islands and 33 artificial islands centered around Bahrain Island, it is located between Qatar and the northeastern coast of Saudi Arabia, to which it is connected by the King Fahd Causeway. The country's geography is characterized by arid desert plains, with its highest point being the Mountain of Smoke (Jabal ad Dukhan). Manama is the capital and largest city.

Historically, Bahrain was the site of the ancient Dilmun civilization, a significant Bronze Age trade center. It was one of the earliest regions to adopt Islam in the 7th century. Over centuries, it experienced rule by various Arab dynasties, the Portuguese, and Persians. In the late 18th century, the Al Khalifa family established their rule, which continues to this day. Bahrain became a British protectorate in the late 19th century and gained independence in 1971. Initially an emirate, Bahrain transitioned to a constitutional monarchy in 2002. The nation's history has been marked by periods of economic prosperity, largely driven by pearl fisheries and later by oil, discovered in 1932, making it the first Gulf state to export petroleum. More recently, Bahrain has sought to diversify its economy, with significant investments in banking, finance, and tourism.

Bahrain's political system is a constitutional monarchy, though the King retains extensive executive powers. The bicameral National Assembly consists of an appointed Shura Council and an elected Council of Representatives. The political landscape has been significantly shaped by the relationship between the ruling Sunni Al Khalifa family and the country's Shia majority population. Tensions culminated in the 2011 Bahraini uprising, part of the broader Arab Spring, which saw widespread protests demanding political reforms and greater respect for human rights. The government's response, including a crackdown on dissent, drew international criticism and has had lasting impacts on Bahraini society and its political dynamics. Human rights issues, including freedom of expression, the rights of political opposition, and the treatment of the Shia population and migrant workers, remain a significant concern.

Economically, Bahrain has transitioned from oil dependence to a more diversified model, with a strong financial services sector. It is recognized as a high-income economy by the World Bank. However, challenges such as youth unemployment and the depletion of natural resources persist. Socially, Bahrain is a mix of traditional Arab culture and modern influences, with a relatively tolerant environment for various faiths compared to some regional neighbors. Education and healthcare are generally well-developed, with universal access for citizens. The country's culture is reflected in its art, literature, music, and sports, including the hosting of the Formula One Bahrain Grand Prix.

2. Etymology

The name Bahrain (البحرينal-BaḥraynArabic) is the dual form of the Arabic word bahr (بحرseaArabic), literally meaning "the two seas". While this is the literal translation, the exact "two seas" to which the name originally referred remains a subject of discussion. Common interpretations suggest it could refer to the bay east and west of the main island, the seas north and south of the island, or the distinct presence of fresh (spring) water sources found within or bubbling up beneath the salty seawater of the Persian Gulf surrounding the islands. This phenomenon of freshwater springs in the sea has been noted by visitors since antiquity.

Historically, the term "Bahrain" was not limited to the current archipelago. Until the late Middle Ages, it denoted a broader region of Eastern Arabia, which included Southern Iraq, Kuwait, Al-Hasa, Qatif, and the present-day islands of Bahrain. This larger region was known as Iqlīm al-Bahrayn (Bahrayn Province). The precise date when "Bahrain" began to refer exclusively to the Awal archipelago, with Awal being an ancient name for the main island, is not definitively known. The island was also commonly spelled "Bahrein" into the 1950s. The medieval grammarian al-Jawahari noted that while Bahrī (meaning "belonging to the sea") might have been a more formally correct term for an inhabitant or aspect of the island, it was likely avoided due to potential misunderstanding. The term al-Bahrayn appears five times in the Quran, but it does not refer to the modern island.

3. History

Bahrain's history spans millennia, from ancient civilizations like Dilmun to its emergence as a modern constitutional monarchy. It has been a strategic trade hub, a center for pearl diving, and has experienced various periods of foreign influence before establishing its sovereignty. The Al Khalifa family's rule began in the late 18th century, leading through British protection to full independence and subsequent political developments, including significant popular movements for reform.

3.1. Antiquity

Bahrain was the heartland of the Dilmun civilization, an important Bronze Age trade center that flourished from the late third millennium to the mid-first millennium BC, linking Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. Archaeological evidence, including extensive burial mounds, particularly the Dilmun Burial Mounds (a UNESCO World Heritage site), attests to its significance. After the decline of Dilmun, Bahrain was successively ruled by the Assyrians and Babylonians.

From the 6th to the 3rd century BC, Bahrain was part of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. Around 250 BC, the Parthian Empire extended its control over the Persian Gulf, establishing garrisons to control trade routes. During the classical era, the ancient Greeks referred to Bahrain as Tylos. It was known as a center for the pearl trade. Nearchus, an admiral serving under Alexander the Great, is believed to have been the first of Alexander's commanders to visit the island. He described it as a verdant land with large cotton plantations, whose manufactured clothes, called sindones, were widely traded. Alexander had plans to settle Greek colonists in Bahrain, and while the scale of this is unclear, Bahrain became significantly Hellenized. The language of the upper classes was Greek, and local coinage depicted a seated Zeus, possibly a syncretized form of the Arabian sun-god Shams. Tylos was also a site for Greek athletic contests. Some historians like Strabo and Herodotus believed that the Phoenicians originated from Bahrain, a theory supported by 19th-century classicist Arnold Heeren, though archaeological evidence for such a migration during the proposed period is limited. The name Tylos is thought to be a Hellenization of the Semitic Tilmun (from Dilmun).

In the 3rd century AD, Ardashir I, the first ruler of the Sasanian (Persian) Empire, conquered Oman and Bahrain. Bahrain, then possibly known as Mishmahig, was also a site for the worship of an ox deity called Awal, after whom the main island was later named for many centuries. By the 5th century, Bahrain became a center for Nestorian Christianity, with the village of Samahij on Muharraq Island serving as the seat of bishops. The pre-Islamic population of Bahrain was diverse, consisting of Christian Arabs (mainly from the Abd al-Qays tribe), Persians (largely Zoroastrians), Jews, and Aramaic-speaking agriculturalists. Syriac functioned as a liturgical language.

3.2. Arrival of Islam

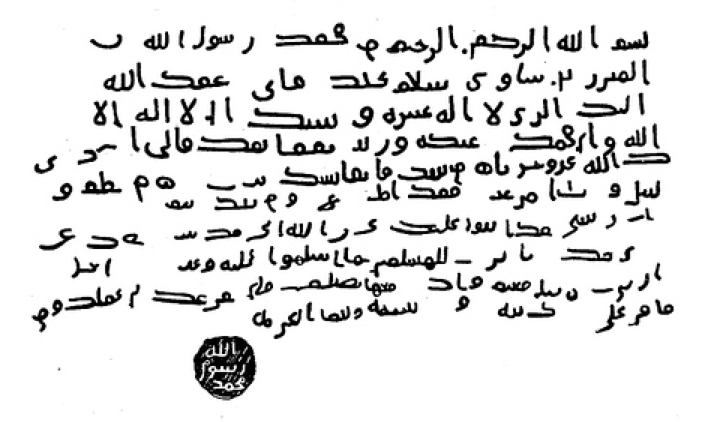

The introduction of Islam to Bahrain occurred during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad around 628 AD. Traditional Islamic accounts state that Muhammad sent an envoy, Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami, to Munzir ibn Sawa Al Tamimi, the Sasanian-appointed governor of the region then known as "Bahrain" (which historically encompassed a larger area of Eastern Arabia including the present-day islands). Munzir ibn Sawa is said to have accepted Islam, and subsequently, the entire area converted. An early interaction mentioned in Islamic tradition is the Al Kudr Invasion, where Muhammad ordered an attack on the Banu Salim tribe for allegedly plotting against Medina, though the tribe retreated upon learning of Muhammad's approach. A letter purported to be from Muhammad to al-Tamimi is preserved at the Beit al-Qur'an Museum in Hoora, Bahrain.

Following the initial conversion, Bahrain became an integral part of the expanding Islamic caliphates. Its strategic location in the Persian Gulf continued to make it an important center for trade and maritime activities under Islamic rule.

3.3. Middle Ages

In 899 AD, the Qarmatians, a millenarian Ismaili Muslim sect, seized Bahrain, seeking to create a utopian society. They established a powerful state in Eastern Arabia with Al-Ahsa as their capital, and Bahrain (the islands) was part of their domain. The Qarmatians famously demanded tribute from the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad and, in 930 AD, sacked Mecca and Medina, carrying the sacred Black Stone back to their base in Ahsa, where it remained for over two decades before being returned under mysterious circumstances in 951.

Following their defeat by the Abbasids in 976, the Qarmatians were overthrown by the Arab Uyunid dynasty of al-Hasa, who took control of the entire Bahrain region in 1076. The Uyunids ruled until 1235, when the archipelago was briefly occupied by the Persian ruler of Fars. In 1253, the Bedouin Usfurids brought down the Uyunid dynasty, gaining control over eastern Arabia, including the islands of Bahrain. By 1330, the archipelago became a tributary state to the rulers of Hormuz, though locally the islands were often controlled by the Shi'ite Jarwanid dynasty of Qatif. In the mid-15th century, the archipelago came under the rule of the Jabrids, a Bedouin dynasty also based in Al-Ahsa that ruled most of eastern Arabia.

3.4. Portuguese and early modern era

In 1521, the Portuguese Empire, allied with Hormuz, seized Bahrain from the Jabrid ruler Muqrin ibn Zamil, who was killed during the takeover. Portuguese rule in Bahrain lasted for approximately 80 years. During this period, they largely depended on Sunni Persian governors to administer the islands. The Portuguese presence aimed to control the lucrative pearl trade and strategic maritime routes in the Persian Gulf.

In 1602, Shah Abbas I of the Safavid dynasty of Persia expelled the Portuguese from Bahrain. This event marked a significant shift, as Safavid rule gave impetus to the spread and consolidation of Shia Islam in the islands, which remains the faith of a majority of Bahraini Muslims today. For the next two centuries, Persian rulers largely retained control of the archipelago, although their rule was interrupted by invasions from the Ibadis of Oman in 1717 and 1738. During much of this period, Persian governance was often indirect, either administered through the city of Bushehr on the Persian coast or through immigrant Sunni Arab clans known as Huwala, who had returned to the Arabian side of the Gulf from Persian territories. In 1753, the Huwala clan of Nasr Al-Madhkur, acting on behalf of the Iranian Zand dynasty leader Karim Khan Zand, invaded Bahrain and restored direct Iranian rule.

3.5. 19th century and later

The late 18th century marked a pivotal moment in Bahrain's history with the arrival of the Al Khalifa family. In 1783, the Bani Utbah tribal confederation, to which the Al Khalifa belong, along with allied tribes, captured Bahrain from Nasr Al-Madhkur, the Persian-appointed governor, following the Battle of Zubarah (1782). Ahmed al Fateh became the first Al Khalifa hakim (ruler) of Bahrain. The Al Khalifa had been present in the region, particularly in Zubarah (in modern-day Qatar), before their conquest of Bahrain.

In the early 19th century, Bahrain faced invasions from both the Omanis and the Wahhabi forces of the First Saudi State. In 1802, an Omani ruler installed his 12-year-old son as governor in Arad Fort. The Al Khalifa sought to consolidate their rule amidst these regional power struggles.

The British Empire's influence in the Persian Gulf grew significantly during the 19th century. In 1820, the Al Khalifa were recognized by the United Kingdom as the rulers of Bahrain after signing the General Maritime Treaty of 1820. This treaty was primarily aimed at curbing piracy in the Gulf, but it also marked the beginning of a formal relationship between Bahrain and Britain. Despite this, Bahrain was forced to pay yearly tributes to Egypt (then under Ottoman suzerainty) a decade later, even while seeking Persian and British protection.

Successive treaties with the British throughout the 19th century progressively transformed Bahrain into a British protectorate. Key agreements in 1861 (Perpetual Truce of Peace and Friendship), 1880, and 1892 solidified this status. These treaties stipulated that the ruler of Bahrain could not dispose of any territory except to the United Kingdom and could not enter into relationships with any foreign government without British consent. In return, Britain promised to protect Bahrain from maritime aggression and lend support in case of land attacks, crucially underpinning the Al Khalifa's rule against internal and external threats, including renewed Persian claims of sovereignty.

British dominance, however, also led to unrest. The first widespread uprising against Sheikh Issa bin Ali, then ruler of Bahrain, occurred in March 1895, partly due to discontent with British influence. British forces were involved in suppressing this revolt. Before the discovery of oil, Bahrain's economy was heavily reliant on its pearl fisheries, considered among the world's finest.

In 1923, the British introduced significant administrative reforms, deposing Sheikh Issa bin Ali and replacing him with his son, Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa (grandfather of the current king). Charles Belgrave was appointed as an advisor to the ruler in 1926 and effectively administered the country until 1957. Belgrave oversaw the establishment of Bahrain's first modern school in 1919 and the official abolition of slavery in 1937. These reforms aimed to modernize the state's apparatus but were also sometimes met with resistance, and some clerical opponents and families were exiled. In 1927, Reza Shah of Iran reasserted claims of sovereignty over Bahrain, prompting Belgrave to take measures to counter Iranian influence, allegedly including encouraging sectarian divisions.

The discovery of oil in 1931 by the Bahrain Petroleum Company (Bapco), a subsidiary of Standard Oil of California (Socal), marked a turning point, bringing new wealth and accelerating modernization.

3.6. Independence

After World War II, anti-British sentiment grew across the Arab world, leading to riots in Bahrain. The British government eventually announced its decision to withdraw its forces from "East of Suez" by the end of 1971. Iran, under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, continued to claim historical sovereignty over Bahrain. However, facing international pressure and a desire for regional stability, Iran agreed to a United Nations-sponsored "ascertainment of wishes" of the Bahraini people regarding their political future. A UN mission found that the overwhelming majority of Bahrainis wished for full independence rather than integration with Iran.

On 15 August 1971, Bahrain declared its independence from British protection, becoming the State of Bahrain. Sheikh Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa became the first Emir. Bahrain quickly joined the United Nations and the Arab League. The oil boom of the 1970s brought considerable prosperity, though the economy remained vulnerable to oil price fluctuations. During the Lebanese Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s, Bahrain benefited as it began to replace Beirut as a key financial hub in the Middle East.

In 1981, following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, a coup attempt allegedly backed by Iran and orchestrated by the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain, a Bahraini Shia group, was thwarted. This event heightened sectarian tensions and government suspicion towards its Shia population. The 1990s saw a period of sustained pro-democracy protests and unrest, known as the "Intifada," involving leftists, liberals, and Islamists demanding political reforms. This period of unrest, which resulted in approximately forty deaths, largely subsided after Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa became the Emir in 1999 upon the death of his father.

Sheikh Hamad initiated a period of political reforms. In 2001, a National Action Charter, proposing significant political changes including the establishment of a constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament and an independent judiciary, was overwhelmingly approved in a referendum. As a result, on 14 February 2002, Bahrain was declared a Kingdom, and Emir Hamad became King. Women were granted the right to vote and stand for office, and political prisoners were released.

3.7. 2011 Bahraini protests and aftermath

Inspired by the wider Arab Spring movements across the Middle East and North Africa, large-scale protests erupted in Bahrain in February 2011. The protesters, largely from the country's Shia majority, initially gathered at the Pearl Roundabout in Manama, demanding political reforms, greater civil liberties, an end to sectarian discrimination, and a constitutional monarchy with an elected government. The human rights situation was a central grievance, with calls for an end to torture, arbitrary arrests, and for accountability for past abuses.

The government's initial response included attempts at dialogue but quickly escalated to a forceful crackdown. On 17 February 2011, a pre-dawn raid by security forces on the protesters' camp at the Pearl Roundabout, an event known as Bloody Thursday, resulted in several deaths and many injuries, further inflaming tensions. While protests were briefly allowed to resume at the roundabout, the situation deteriorated.

In March 2011, the Bahraini government requested assistance from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The Peninsula Shield Force, predominantly composed of Saudi Arabian and Emirati troops, entered Bahrain to support the government in quelling the unrest. A state of emergency was declared, and a severe crackdown ensued. Security forces conducted widespread arrests, targeting protesters, activists, medics, and opposition figures. There were extensive reports of human rights violations, including excessive use of force, systematic torture in detention, denial of due process, and restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly. The Pearl Roundabout monument, a symbol of the uprising, was demolished by the government.

The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI), established by King Hamad, released a report in November 2011. The BICI report confirmed many of the human rights abuses, including systematic torture and excessive force, and made recommendations for reform and accountability. While the government accepted the findings and pledged reforms, human rights organizations have since reported that many of these reforms have not been adequately implemented and that human rights violations have continued.

The aftermath of the 2011 uprising has been characterized by an ongoing low-level conflict, with sporadic protests and clashes between demonstrators and security forces. The government has dissolved major opposition political societies like Al-Wefaq and Al-Wa'ad, imprisoned prominent human rights defenders and opposition leaders (such as Nabeel Rajab, Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, and Sheikh Ali Salman), and revoked the citizenship of hundreds of individuals. Freedom of expression and the media remain severely restricted. International human rights organizations and some foreign governments have continued to express concern over the human rights situation in Bahrain and the lack of meaningful political reconciliation and democratic progress. The social fabric has been deeply affected, with increased sectarian polarization. The government has often accused Iran of interfering in its internal affairs and fueling the unrest, a charge Iran denies. The events of 2011 and their aftermath continue to shape Bahrain's political, social, and human rights landscape.

4. Geography

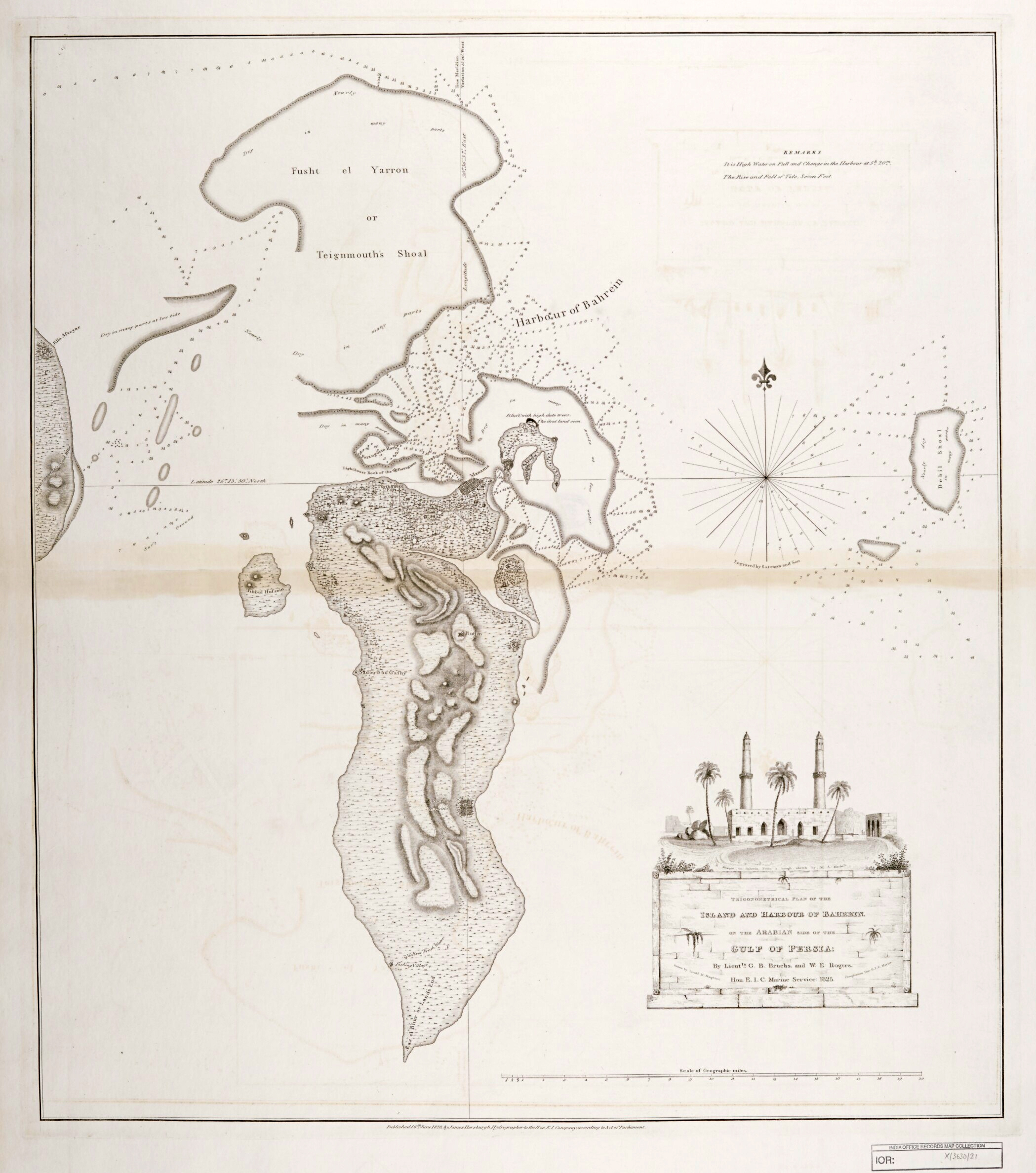

Bahrain is an archipelago located in the Persian Gulf, east of Saudi Arabia and west of Qatar. The country consists of 50 natural islands and an additional 33 artificial islands, with Bahrain Island being the largest, accounting for about 83% of the country's total landmass. Due to extensive land reclamation, Bahrain's total area has increased from approximately 257 mile2 (665 km2) to about 303 mile2 (785 km2). The highest point in Bahrain is Jabal ad Dukhan (Mountain of Smoke), a low escarpment reaching 440 ft (134 m) above sea level. Bahrain has a coastline of 100 mile (161 km) and does not share any land boundaries. Major islands include Bahrain Island, Hawar Islands (a disputed territory with Qatar, awarded to Bahrain by the ICJ in 2001), Muharraq Island, Umm an Nasan, and Sitra.

The geography is predominantly flat and arid, characterized by low desert plains. Natural resources include oil and natural gas, as well as fish in the offshore waters. Only about 2.82% of the land is arable. Environmental challenges include desertification, coastal degradation from oil spills and land reclamation (such as in Tubli Bay), and the salinization of the Dammam Aquifer, the country's primary source of fresh water, due to over-extraction.

4.1. Climate

Bahrain features an arid climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). Summers, from April to October, are very hot and humid, with temperatures potentially reaching up to 122 °F (50 °C). The shallow seas surrounding Bahrain heat up quickly in the summer, contributing to high humidity, especially at night. Winters, from December to March, are mild, with temperatures typically ranging between 66.2 °F (19 °C) and 84.2 °F (29 °C).

Rainfall is minimal and irregular, averaging about 2.8 in (71 mm) annually, occurring mostly during the winter months. The Zagros Mountains across the Persian Gulf in Iran influence local weather patterns, and northwesterly winds, known as the shamal wind, can bring dust storms from Iraq and Saudi Arabia, particularly in June and July, reducing visibility.

Bahrain is highly vulnerable to the impacts of global climate change, including more frequent extreme heat, droughts, dust storms, and the threat of sea-level rise, which endangers its coastal areas, food security, and water resources. Despite being a relatively low overall emitter of greenhouse gases, Bahrain had the second-highest per capita emissions in 2023. The majority of its emissions originate from burning fossil fuels in the energy sector. The nation has committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2060 and aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2035. In April 2024, Bahrain, along with other Gulf countries, experienced significant flooding due to unusually heavy rainfall.

4.2. Biodiversity

Bahrain's ecosystems support a variety of flora and fauna adapted to its arid and marine environments. Over 330 species of birds have been recorded in the archipelago, with 26 species breeding in the country. The islands serve as an important stopover for millions of migratory birds. The Socotra cormorant has globally significant breeding colonies on the Hawar Islands. The national bird of Bahrain is the bulbul, and the national animal is the Arabian oryx.

Mammal species are less numerous, with only about 18 recorded, including gazelles, desert rabbits, and hedgehogs; the Arabian oryx was hunted to extinction on the main island but has been reintroduced in captivity. The country is also home to 25 species of amphibians and reptiles, 21 species of butterflies, and 307 species of flora.

Marine biotopes are diverse, featuring extensive sea grass beds, mudflats, and patchy coral reefs. These habitats are crucial for species like dugongs and the green turtle. In 2003, Bahrain banned the capture of sea cows (dugongs), marine turtles, and dolphins within its territorial waters.

Bahrain has five designated protected areas, four of which are marine environments:

- Hawar Islands: A Ramsar site, internationally recognized for bird migration and the world's largest breeding colony of Socotra cormorants.

- Mashtan Island

- Arad Bay (in Muharraq)

- Tubli Bay

- Al Areen Wildlife Park: A zoo and breeding center for endangered animals, it is the only protected area on land and is actively managed.

Key environmental challenges include desertification, degradation of limited arable land, and coastal damage from oil spills, industrial discharges, and land reclamation.

5. Government and politics

Bahrain is a constitutional monarchy headed by the King, Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. The Al Khalifa family has ruled Bahrain since 1783. The current Prime Minister is Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, who succeeded the long-serving Sheikh Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa in 2020. The King holds wide executive powers, including appointing the prime minister and cabinet ministers, commanding the armed forces, chairing the Higher Judicial Council, appointing the upper house of parliament, and dissolving the elected lower house. The 2002 constitution established Islam as the state religion and Sharia as a principal source for legislation.

The political system includes a bicameral National Assembly (al-Majlis al-Watani). It consists of:

- The Shura Council (Majlis Al-Shura): The upper house with 40 members appointed by the King.

- The Council of Representatives (Majlis Al-Nuwab): The lower house with 40 members elected by absolute majority vote in single-member constituencies for four-year terms.

The Shura Council exercises a de facto veto over legislation passed by the Council of Representatives, as draft acts require its approval to become law. Parliamentary elections were first held in 1973 but the parliament was dissolved two years later. Following the 2002 constitution, parliamentary elections were reinstated. Major opposition groups, particularly Al-Wefaq, which represented a significant portion of the Shia population, participated in elections in 2006 and 2010, winning a plurality of seats. However, Al-Wefaq's MPs resigned in 2011 in protest against the government's crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators, and the society was later dissolved by the authorities. Subsequent elections have been boycotted by parts of the opposition. The political landscape is heavily influenced by sectarian divisions between the Sunni ruling elite and the Shia majority, who have often voiced concerns about political marginalization and discrimination. This has led to significant human rights challenges and calls for democratic reform.

5.1. Governorates

Bahrain is divided into four governorates. Until July 2002, it was divided into twelve municipalities. In September 2014, the Central Governorate was dissolved and its territory was divided among the Capital, Northern, and Southern Governorates. The current governorates are:

- Capital Governorate

- Muharraq Governorate

- Northern Governorate

- Southern Governorate

5.2. Military

The Bahrain Defence Force (BDF) is the military of Bahrain. It numbers around 18,000 active personnel (as of 2023) and consists of the Royal Bahraini Army, the Royal Bahraini Air Force, the Royal Bahraini Navy, and the Royal Guard. The Bahrain National Guard is a separate force of about 2,000 personnel tasked with assisting the BDF and maintaining internal security. The King is the Supreme Commander of the BDF, and the Crown Prince is the Deputy Supreme Commander. Field Marshal Khalifa bin Ahmed Al Khalifa has been the Commander-in-Chief of the BDF since 2008.

The BDF is primarily equipped with hardware from the United States and other Western countries. Key equipment includes F-16 Fighting Falcon and F-5 Freedom Fighter aircraft, UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters, M60A3 tanks, and naval vessels like the former USS Jack Williams (renamed RBNS Sabha) and the former USS Robert G. Bradley (renamed RBNS Khalid bin Ali). Bahrain was the first Gulf country to operate the F-16 and is upgrading its fleet with F-16 Block 70 aircraft.

Bahrain has a close defense relationship with the United States and hosts the U.S. Navy's Fifth Fleet and U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) at Naval Support Activity Bahrain in Juffair. This base is a critical U.S. military installation in the region, with around 6,000 U.S. military personnel stationed there. The United Kingdom also maintains a naval base, HMS Juffair, at Mina Salman, which was officially opened in 2018.

Bahrain has participated in regional military actions, including the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against Houthi forces.

5.3. Foreign relations

Bahrain maintains diplomatic relations with 190 countries worldwide and has a network of 25 embassies, 3 consulates, and 4 permanent missions to international organizations like the Arab League, the United Nations, and the European Union. The country hosts 36 foreign embassies. As a Major non-NATO ally of the United States, Bahrain plays a significant role in regional security cooperation.

Bahrain is a founding member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and generally aligns its foreign policy with other GCC states, particularly Saudi Arabia. It adheres to the Arab League's positions on Middle East peace and Palestinian rights, supporting a two-state solution.

Relations with Iran have historically been tense, particularly following the 1979 Iranian Revolution and a failed coup attempt in Bahrain in 1981, which Bahrain attributed to Iranian instigation. Iran has also periodically made historical sovereignty claims over Bahrain. In 2016, Bahrain, along with Saudi Arabia, severed diplomatic ties with Iran following an attack on the Saudi embassy in Tehran.

In a significant foreign policy shift, Bahrain normalized relations with Israel in 2020 as part of the Abraham Accords, brokered by the United States. This move was seen as part of a broader regional realignment, partly aimed at countering Iranian influence.

Bahrain's foreign policy is often influenced by its geographical location, its reliance on larger regional powers like Saudi Arabia for security and economic support, and its efforts to balance relationships with global powers. Human rights concerns raised by international bodies and other nations sometimes feature in its bilateral relations. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Bahrain was ranked the 81st most peaceful country in the world.

5.4. Human rights

The human rights situation in Bahrain has been a subject of significant international concern, particularly since the 2011 pro-democracy uprising. While the government, led by King Hamad Al Khalifa, initiated some reforms in the early 2000s, which were initially described by organizations like Amnesty International as a "historic period of human rights," conditions deteriorated, especially after 2007 with reports of torture resurfacing.

The period between 1975 and 1999, under the State Security Law, was marked by widespread violations, including arbitrary arrests, detention without trial, torture, and forced exile. Following the 2011 uprising, which was met with a severe government crackdown, numerous human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, documented grave abuses. These included excessive use of force by security forces, systematic torture and ill-treatment of detainees, deaths in custody, arbitrary arrests and detentions, unfair trials (including trials of civilians in military courts), and severe restrictions on freedoms of expression, association, and assembly.

The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI), established by the King, confirmed many of these abuses in its November 2011 report and made recommendations for reform. However, the implementation of these recommendations has been widely criticized as inadequate. Opposition political societies, such as Al-Wefaq and Wa'ad, were dissolved, and prominent human rights defenders, activists, and opposition leaders have been imprisoned, often on charges related to freedom of expression or assembly. Figures like Nabeel Rajab and Abdulhadi al-Khawaja faced lengthy prison sentences.

Key areas of concern highlighted by human rights groups include:

- Freedom of Expression and Media: Severe restrictions, censorship, prosecution of journalists and online activists.

- Freedom of Assembly and Association: Bans on protests, dissolution of opposition groups.

- Torture and Ill-treatment: Persistent allegations of torture and ill-treatment in detention centers.

- Due Process and Fair Trials: Concerns about the independence of the judiciary and the fairness of trials, especially in politically motivated cases.

- Sectarian Discrimination: Reports of discrimination against the Shia majority population in government employment, education, and the justice system. The US State Department has also noted these concerns.

- Migrant Workers' Rights: Conditions for migrant workers, who form a large part of the population, remain a concern, despite some reforms to the kafala (sponsorship) system.

- Revocation of Citizenship: Hundreds of individuals, including activists and dissidents, have had their citizenship revoked, rendering some stateless.

- Death Penalty: Increased use of the death penalty, with concerns about convictions based on confessions allegedly obtained through torture.

Freedom House has consistently rated Bahrain as "Not Free." The European Parliament and various UN bodies have also expressed serious concerns and called for reforms. While the government has established institutions like the National Institution for Human Rights and an Ombudsman's office, their independence and effectiveness have been questioned by critics. The government often denies systematic abuses and attributes unrest to foreign interference, particularly from Iran.

5.4.1. Women's rights

Women in Bahrain gained the right to vote and stand in national elections in the 2002 constitutional reforms. However, in the 2002 elections, no women were elected to the Council of Representatives. In response, six women were appointed to the Shura Council, including representatives from the indigenous Jewish and Christian communities. Dr. Nada Haffadh became the country's first female cabinet minister when appointed Minister of Health in 2004. Lateefa Al Gaood became the first woman elected to the Council of Representatives in 2006, winning by default. The number of women MPs increased to four after the 2011 by-elections and has seen further modest increases in subsequent elections.

Bahraini women have made significant strides in education and workforce participation. The Supreme Council for Women, chaired by Princess Sabeeka bint Ibrahim Al Khalifa (the King's wife), was established in 2001 to promote women's status and integrate their needs into national development programs. Bahrain has appointed women to high-profile international roles, such as Haya Rashed Al-Khalifa, who served as President of the United Nations General Assembly in 2006, and Houda Nonoo, who became the Arab world's first Jewish ambassador when appointed as Bahrain's ambassador to the United States in 2008. Alees Samaan, a Christian woman, was appointed ambassador to the United Kingdom in 2011.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Women's rights activists like Ghada Jamsheer have criticized some government reforms as "artificial and marginal," arguing that the government uses women's rights as a "decorative tool" internationally while hindering non-governmental women's societies. Issues such as personal status laws, which are based on religious (Sharia) interpretations and differ for Sunni and Shia citizens, can lead to discrimination against women in matters of marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance. Efforts to pass a unified family law have faced resistance from some religious conservatives. Domestic violence and the full realization of equal opportunities in all sectors continue to be areas of focus for women's rights advocates.

5.4.2. Media and freedom of expression

The media landscape in Bahrain is characterized by significant government control and restrictions on freedom of expression. While there is a variety of media outlets, including daily and weekly newspapers in Arabic, English, and other languages (such as Malayalam for the expatriate community), as well as state-run television and radio networks, critical reporting is severely limited.

Major Arabic daily newspapers include Akhbar Al Khaleej and Al Ayam, while English dailies include the Gulf Daily News and the Daily Tribune. State-run television operates five networks, and state radio broadcasts primarily in Arabic, though Radio Bahrain (English) and Your FM (for South Asian expatriates) also operate.

Internet penetration is high, with over 961,000 users by June 2012. However, the online sphere is heavily monitored and filtered. Authorities target political, human rights, and religious content deemed sensitive or obscene. Bloggers, netizens, and social media users have faced arrest, detention, and prosecution for expressing critical views, particularly since the 2011 uprising.

Journalists in Bahrain risk prosecution for a range of offenses, including "undermining" the government or religion, and self-censorship is widespread. During the 2011 protests, journalists were targeted by officials, and several foreign correspondents were expelled. The opposition daily Al-Wasat faced repeated suspensions and pressure, with its editors being fined for publishing "false" news, before its eventual closure. The BICI report in 2011 found that state media coverage was at times inflammatory and recommended that the government "consider relaxing censorship" and improve opposition access to mainstream media.

International press freedom organizations like Reporters Without Borders consistently rank Bahrain among the world's most restrictive regimes for press freedom. The government's actions have been criticized for stifling democratic discourse and creating an environment of fear for those who might express dissent.

6. Economy

Bahrain has the first "post-oil" economy in the Persian Gulf, having invested significantly in diversifying its economic base away from heavy reliance on oil and gas. According to a 2006 UNESWCA report, Bahrain had the fastest-growing economy in the Arab world at that time, and the Index of Economic Freedom has often ranked it highly in the Middle East.

The country has established itself as a major financial hub, particularly in Islamic banking. Many of the world's largest financial institutions have a presence in Manama. Petroleum production and processing remain significant, accounting for approximately 60% of export receipts, 70% of government revenues, and 11% of GDP in earlier estimates, though these proportions have been decreasing with diversification efforts. Aluminium Bahrain (Alba) is one of the world's largest aluminum smelters and a key non-oil industry. Other important sectors include tourism, construction, and manufacturing.

The government launched "Bahrain Economic Vision 2030" in 2008, a long-term plan aimed at transforming the economy to be more sustainable, competitive, and fair, driven by the private sector. Key policy initiatives include attracting foreign investment, developing infrastructure, and enhancing the skills of the national workforce.

Economic conditions have fluctuated with oil prices, but Bahrain's diversified base has provided some resilience. The country depends heavily on food imports, as only about 2.9% of its land is arable, and agriculture contributes minimally to GDP. In 2004, Bahrain signed a Free Trade Agreement with the United States.

The Great Recession and the 2011 uprising impacted economic growth, with GDP growth slowing to 1.3% in 2011. Public debt has risen, reaching 130% of GDP in 2020 and projected to increase further, partly due to military expenditure and social support programs. Access to biocapacity is low, and Bahrain runs a significant ecological footprint deficit. Unemployment, particularly among youth, and the depletion of oil and underground water resources are long-term economic challenges. Bahrain was the first Arab country to institute unemployment benefits in 2007.

6.1. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector of Bahrain's economy. The country received over eleven million visitors in 2019, a majority from neighboring Arab states, but with an increasing number of international tourists drawn by its rich heritage, modern attractions, and events like the Bahrain Grand Prix.

Key attractions include:

- Historical and Archaeological Sites:** Qal'at al-Bahrain (Bahrain Fort), a UNESCO World Heritage site; the extensive Dilmun Burial Mounds; the Bahrain National Museum, showcasing artifacts from 9,000 years of history; Beit Al Quran, a museum of Islamic artifacts and Qur'ans; the ancient Al Khamis Mosque; Arad Fort; the Barbar and Saar temples from the Dilmunite period.

- Natural Attractions:** The Tree of Life, a solitary, centuries-old Prosopis cineraria tree in the Sakhir desert; the Hawar Islands for bird watching.

- Modern Attractions and Leisure:** Shopping malls like Bahrain City Centre and Seef Mall; traditional markets like Manama Souq and the Gold Souq; scuba diving and horse riding. In 2019, an underwater theme park featuring a sunken Boeing 747 was announced.

- Cultural Events:** The annual Spring of Culture festival in March, featuring international musicians and artists. Manama was named Arab Capital of Culture for 2012 and Capital of Arab Tourism for 2013.

The government actively promotes tourism as part of its economic diversification strategy, aiming to combine modern Arab culture with its rich historical legacy.

6.2. Value Added Tax (VAT)

The Kingdom of Bahrain introduced Value Added Tax (VAT) on 1 January 2019, at a standard rate of 5%. This tax applies to the sale of most goods and services. The National Bureau for Revenue (NBR) is responsible for managing and collecting VAT. On 1 January 2022, the standard VAT rate was increased to 10%. The introduction of VAT is part of broader fiscal reforms in GCC countries aimed at diversifying government revenue sources away from hydrocarbon dependency. The government has implemented measures to ensure compliance, including penalties for defaults and audits, often engaging international accounting firms for advisory services. Certain goods and services, such as basic food items, healthcare, education, and local transportation, may be zero-rated or exempt from VAT.

6.3. Infrastructure

6.3.1. Transport

Bahrain's primary international gateway is the Bahrain International Airport (BAH), located on Muharraq Island. A new, significantly larger passenger terminal was opened in January 2021, substantially increasing its capacity to handle 14 million passengers annually. The national carrier, Gulf Air, is based at BAH.

The road network is extensive and well-maintained, particularly in Manama and connecting major urban areas. A series of causeways and bridges link the main islands. The most notable is the 16 mile (25 km) King Fahd Causeway, which has connected Bahrain to mainland Saudi Arabia since 1986 and is vital for trade and travel. Plans are underway for a second causeway to Saudi Arabia, the King Hamad Causeway, which is expected to include a rail link.

The main seaport is Mina Salman, which handles a significant portion of the country's cargo. In 2001, Bahrain had a merchant fleet of eight ships of 1,000 GT or over. Private vehicles and taxis are the primary modes of urban transportation. A nationwide metro system is currently under construction, with the first phase expected to be operational in the coming years, aiming to alleviate traffic congestion and improve public transport.

6.3.2. Telecommunications

The telecommunications sector in Bahrain is advanced. Batelco, established in 1981, was the monopoly provider until the market was liberalized. The Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (TRA) was established in 2002 to oversee the sector. Other major mobile service providers include Zain (since 2004) and STC Bahrain (formerly VIVA) (since 2010).

Bahrain has been connected to the internet since 1995, with the country domain suffix being .bh. Internet penetration is very high; in 2008, the country's connectivity score (internet, fixed and mobile lines) was 210.4 per person. The number of internet users grew rapidly from 40,000 in 2000 to over 1.3 million by 2016. The TRA has licensed numerous Internet Service Providers. Fiber optic networks are widely available, supporting high-speed internet access.

6.4. Science and technology

Bahrain has outlined goals for developing its science and technology sector as part of its Bahrain Economic Vision 2030, aiming to shift from an oil-based economy to a productive, globally competitive one. However, investment in research and development (R&D) has historically been low, reported at around 0.04% of GDP in 2013 (covering only higher education).

Key institutions include the University of Bahrain (established 1986) and the Bahrain Centre for Strategic, International, and Energy Studies (DERASAT, founded 2009). Initiatives to foster a science culture include the Bahrain Science Centre, launched in 2013 for young people. In 2014, Bahrain established its National Space Science Agency, aiming to develop infrastructure for space and Earth observation and ratify international space treaties. A UNESCO Regional Centre for Information and Communication Technology was established in Manama in 2012 to serve GCC states.

Bahrain has high internet penetration (90% in 2013, topping the Arab world). Government spending on education was 2.6% of GDP in 2012, relatively low for the Arab region. The country was ranked 72nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2024. The number of researchers is also low compared to global averages.

The University of Bahrain had over 20,000 students in 2014 (65% women) and around 900 faculty (40% women). Women accounted for 66% of graduates in natural sciences in 2014. Scientific research output, measured by publications in internationally catalogued journals, has been modest but slowly increasing. In 2014, Bahraini scientists published 155 articles (15 per million inhabitants). Main research collaboration partners include Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UK, the US, and Tunisia.

7. Demographics

In 2010, Bahrain's population was approximately 1.2 million, of which 568,399 (about 46%) were Bahraini nationals and 666,172 (about 54%) were non-nationals. By May 2023, the population was estimated at 1,501,635, with expatriates, largely from South Asia (especially India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) and other Arab countries, constituting a significant majority (around 52-55%). The Indian community is the largest single expatriate group.

Bahrain is one of the most densely populated sovereign states in the world. Most of the population is concentrated in the northern part of the country, particularly in and around the capital, Manama, and Muharraq. The Southern Governorate is the least densely populated.

7.1. Ethnic groups

The Bahraini citizen population is ethnically diverse.

- Baharna: Constitute the indigenous Arab Shia community, historically settled agriculturalists.

- Ajam: Bahrainis of Persian (Iranian) descent, mostly Shia. They form significant communities in Manama and Muharraq.

- Arab Sunnis (Al Arab): Descendants of tribal Arabs from the Arabian Peninsula, including the ruling Al Khalifa family. They are traditionally concentrated in areas like Zallaq, Muharraq, Riffa, and the Hawar Islands. This group is the most influential politically.

- Huwala: Descendants of Sunni Arabs or Sunni Persians who migrated from Persia to the Arab side of the Gulf.

- Other groups: Smaller communities include Bahrainis of Baloch origin (Sunni) and African Bahrainis (descendants from East Africa), traditionally living in Muharraq and Riffa.

The presence of a large expatriate workforce adds further ethnic diversity, though these groups generally do not hold Bahraini citizenship. There have been concerns and allegations regarding the naturalization of foreign Sunnis, primarily for security force recruitment, which critics claim is an attempt to alter the country's demographic balance.

7.2. Religion

| Religion | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Islam | 69.7% |

| Christianity | 14.1% |

| Hinduism | 10.2% |

| Buddhism | 3.1% |

| Jewish | 0.002% |

| Other faiths | 0.9% |

| Unaffiliated | 2.0% |

Islam is the state religion of Bahrain. Among Bahraini citizens, Muslims constitute the vast majority. While official government statistics on sectarian breakdown are not regularly published, it is widely estimated that Shia Muslims form a majority of the Bahraini Muslim citizen population (estimates vary, often cited between 60-75%), while the ruling Al Khalifa family and the political and military elite are predominantly Sunni Muslims. This sectarian dynamic is a significant factor in Bahrain's politics and society, with a history of grievances from the Shia community regarding political marginalization and discrimination.

The overall population, including expatriates, presents a more diverse religious landscape. According to a 2020 Pew Research estimate, 70.3% of the total population is Muslim, 14.5% Christian, 9.8% Hindu, 2.5% Buddhist, with smaller numbers of Jews and other faiths. The 2010 census recorded that the Muslim proportion of the total population was 70.2%.

Bahrain has a small indigenous Christian community (approximately 1,000 citizens) and a very small indigenous Jewish community (around 30-50 citizens). Expatriate Christians, largely from South Asia, the Philippines, and Western countries, form the majority of Christians in Bahrain. There is also a significant Hindu community, primarily consisting of Indian expatriates; the historic Shrinathji Temple in Manama is over 200 years old and serves this community. Religious freedom is officially stated, and non-Muslim communities are generally allowed to practice their faith, though proselytizing by non-Muslims is restricted.

7.3. Languages

The official language of Bahrain is Arabic. The spoken dialect is Bahrani Arabic, which has distinct features compared to Modern Standard Arabic and other Gulf dialects. English is widely used as a second language, especially in business, education, and by the large expatriate population. All commercial institutions and road signs are bilingual, displaying both Arabic and English.

Due to the diverse expatriate communities, several other languages are commonly spoken, including:

- Persian (Farsi): Spoken by the Ajam community and some other residents.

- Urdu and Hindi: Widely spoken by expatriates from Pakistan and India.

- Balochi: Spoken by Bahrainis of Baloch origin.

- Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Bangla: Spoken by significant communities from South India and Bangladesh.

- Nepali: Spoken by Nepalese workers and Gurkha soldiers.

Fluency in Arabic is a constitutional requirement for members of parliament.

7.4. Education

Education in Bahrain is compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 14 and is free for Bahraini citizens in public schools. The Ministry of Education provides textbooks and oversees the system. Public schools are generally segregated by gender.

The modern public school system began in 1919 with the Al-Hidaya Al-Khalifia School for boys in Muharraq, followed by a second boys' school in Manama in 1926, and the first public school for girls in Muharraq in 1928. Prior to this, Qur'anic schools (Kuttab) were the primary form of education. In 2004, King Hamad launched the "King Hamad Schools of Future" project to integrate Information and Communication Technology (ICT) into K-12 education, aiming to connect all schools with the Internet.

In addition to public schools, there are numerous private and international schools. The Bahrain School, a U.S. Department of Defense school, offers a K-12 curriculum including the International Baccalaureate (IB) program. Other international schools offer IB or UK A-Levels.

Higher education institutions include the public University of Bahrain (the largest), the Arabian Gulf University (a GCC regional university), and the College of Health Sciences. Private universities have also been established, such as Ahlia University, University College of Bahrain, and the Royal University for Women (RUW), the first private international university in Bahrain dedicated solely to educating women. The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) established a constituent medical university, RCSI-Bahrain. Other specialized institutes include the Bahrain Institute of Banking and Finance (BIBF).

Literacy rates are high, and Bahrain has made significant progress in educational attainment, particularly for women.

7.5. Health

Bahrain has a universal health care system, established in 1960. Healthcare provided by the government is free for Bahraini citizens and heavily subsidized for non-Bahrainis. Healthcare expenditure accounted for 4.5% of Bahrain's GDP according to WHO. Unlike some neighboring Gulf states, Bahraini physicians and nurses constitute a majority of the health sector workforce.

The first hospital in Bahrain was the American Mission Hospital, opened in 1893. The first public hospital, the Salmaniya Medical Complex in Manama, opened in 1957 and serves as the country's primary tertiary care hospital. Several private hospitals also operate in the country, such as the International Hospital of Bahrain.

Life expectancy is approximately 73 years for males and 76 years for females. The prevalence of HIV/AIDS is relatively low. Malaria and tuberculosis are not major indigenous problems, and cases have declined significantly. The Ministry of Health conducts regular vaccination campaigns.

Public health challenges include high rates of lifestyle-related diseases. Bahrain faces an obesity epidemic, with 28.9% of males and 38.2% of females classified as obese. The country also has one of the world's highest prevalence rates of diabetes mellitus (ranking 5th globally), affecting over 15% of the population and accounting for 5% of deaths. Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death (32%), followed by cancer. Genetic blood disorders such as sickle-cell disease and thalassemia are prevalent, with studies indicating high carrier rates among the Bahraini population (18% for sickle-cell anemia and 24% for thalassemia).

8. Culture

Bahraini culture is a blend of its Arab-Islamic heritage and influences from various interactions throughout its history as a trade and maritime center. While Islam is the state religion and deeply ingrained in daily life, Bahrain is often perceived as more socially liberal and tolerant towards other faiths and lifestyles compared to some of its conservative neighbors. This tolerance is particularly visible in Manama, the capital.

Traditional Bahraini social customs emphasize hospitality and respect. Intermarriages between Bahrainis and expatriates, though not the norm, do occur. Rules regarding female attire are generally more relaxed than in stricter Gulf countries. While many Bahraini women wear the traditional hijab (headscarf) or abaya (full-length black cloak), it is not legally mandated for all, and styles vary. The traditional male attire is the thobe (a long white robe), often worn with traditional headdresses like the keffiyeh (ghutra) and agal. However, Western clothing is also common, especially in professional settings and among younger generations.

Homosexuality was decriminalized in Bahrain in 1976, which is unique among Gulf Muslim countries. However, laws pertaining to public morality and indecency are broadly written and have been used to arrest individuals for homosexual acts, particularly if they are public or deemed to contravene social norms. Social acceptance remains limited.

8.1. Art

The modern art movement in Bahrain officially emerged in the 1950s, leading to the establishment of art societies. Popular forms include Expressionism, Surrealism, and calligraphic art. Abstract expressionism has gained traction in recent decades. Traditional crafts such as pottery-making (notably in A'ali village) and textile-weaving (especially in Bani Jamrah village) are important cultural heritage products.

Arabic calligraphy is highly valued, and the government has been an active patron of Islamic art. The Beit Al Quran (House of Qur'an) in Manama is a significant institution dedicated to the Qur'an and Islamic art. The Bahrain National Museum houses a permanent contemporary art exhibition. The annual Spring of Culture festival, organized by the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities, is a major event promoting visual and performing arts, featuring local and international artists.

The architecture of Bahrain shares similarities with that of its Persian Gulf neighbors. The windcatcher, designed for natural ventilation, is a characteristic feature of older buildings, particularly in the historic districts of Manama and Muharraq.

8.2. Literature

Literature holds a strong tradition in Bahrain. Most traditional writers and poets compose in the classical Arabic style. In recent years, there has been a rise in younger poets influenced by Western literature, often writing in free verse and addressing political or personal themes. Ali Al Shargawi, a long-decorated poet, is considered a significant literary figure in Bahrain. Historically, Bahrain is linked to the ancient land of Dilmun, mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Legend also suggests it might have been the location of the mythical Garden of Eden. The National Library of Bahrain, located at the Isa Cultural Centre, serves as a key repository for literature and knowledge.

8.3. Music

The music of Bahrain is similar to that of its neighbors in the Gulf region. The Khaliji style of folk music is popular. Another prominent traditional genre is Sawt, a complex form of urban music typically performed with an oud (plucked lute), a violin, and a mirwas (a type of drum). Ali Bahar and his band Al-Ekhwa (The Brothers) were among Bahrain's most famous popular musicians. Bahrain was also the site of the first recording studio in the Persian Gulf states. Western popular music is also widely listened to, and local artists often blend traditional and modern influences.

8.4. Festivals and leisure

Bahrain hosts several major cultural events and festivals throughout the year. The most prominent is the Spring of Culture festival, usually held in March and April, which features a diverse program of international and local music concerts, art exhibitions, theatrical performances, and lectures. Other events include the Bahrain Summer Festival and Ta'a Al-Shabab (Youth Festival), typically held between August and September, and the Bahrain International Music Festival in October. These festivals are organized by the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities and play a significant role in the country's cultural life and tourism promotion.

Common leisure activities for residents and visitors include shopping in modern malls or traditional souqs, dining out, visiting historical sites, and enjoying coastal activities. Cultural facilities include museums, art galleries, and theaters.

8.5. Sports

A variety of sports are popular in Bahrain. Football (soccer) is the most popular sport. The Bahrain national team competes in regional and international competitions, including the AFC Asian Cup and FIFA World Cup qualifiers, although it has never qualified for the World Cup finals. The country has its own top-tier domestic league, the Bahraini Premier League. In 2019, the national team achieved significant success by winning both the WAFF Championship and the Arabian Gulf Cup for the first time. In 2020, Bahraini investors acquired a minority stake in the French football club Paris FC.

Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) has gained considerable traction. Bahrain hosted the IMMAF World Championships of Amateur MMA and is home to Brave Combat Federation, a significant MMA promotion. KHK MMA, under royal patronage, supports the development of MMA and trains fighters. Cricket is also popular, particularly among the South Asian expatriate community, with the Bahrain Premier League established in 2018.

Motorsport is prominent, with Bahrain hosting the Bahrain Grand Prix, a Formula One race, at the Bahrain International Circuit in Sakhir since 2004. It was the first F1 Grand Prix held in the Middle East. The event was cancelled in 2011 due to the uprising but resumed in 2012 amidst controversy. The circuit also hosts other motorsport events, including drag racing and the Australian V8 Supercar series (Desert 400) in the past.

Other popular sports include basketball, rugby, and horse racing. The Bahraini government also sponsored a UCI WorldTeam cycling team, Bahrain-Merida (now Bahrain Victorious), which has participated in events like the Tour de France. In athletics, Bahrain has achieved international success, often through the naturalization of athletes from African countries.