1. Overview

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta (Repubblika ta' MaltaRepubblika ta' MaltaMaltese), is an island country in Southern Europe, located in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago situated approximately 50 mile (80 km) south of Italy, 176 mile (284 km) east of Tunisia, and 207 mile (333 km) north of Libya. With a population of about 542,000 spread over an area of 122 mile2 (316 km2), Malta is one of the world's smallest and most densely populated countries. The capital city, Valletta, is the smallest national capital in the European Union by area and population. The official languages are Maltese, which is the national language, and English.

Malta's strategic location in the central Mediterranean has endowed it with a rich and complex history, shaped by a succession of powers including the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, the Crown of Aragon, the Knights of St. John, the French, and the British. This long history of foreign rule has profoundly influenced Maltese culture, evident in its language, art, architecture, and cuisine. The country has a strong Christian heritage, with Roman Catholicism being the state religion, traditionally linked to the shipwreck of St. Paul on the island.

Malta achieved independence from the United Kingdom in 1964, becoming a state within the Commonwealth of Nations, and transitioned to a republic in 1974. It has since established itself as a parliamentary republic, fostering democratic institutions and processes. Malta joined the European Union in 2004 and the Eurozone in 2008, further integrating itself into the European political and economic landscape. The nation's foreign policy emphasizes neutrality and participation in international organizations, advocating for peace and cooperation.

The Maltese economy is advanced and high-income, primarily driven by tourism, financial services, manufacturing (particularly electronics and pharmaceuticals), and iGaming. The country attracts visitors with its warm climate, historical sites, including three UNESCO World Heritage Sites (the City of Valletta, the Megalithic Temples, and the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum), and vibrant cultural life. Social aspects such as human rights, including LGBT rights, freedom of religion, and the rights of migrants and persons with disabilities, are important components of Malta's contemporary social fabric, reflecting a commitment to social liberal values and democratic development. The country continues to navigate challenges related to high population density, urbanisation, and environmental sustainability.

2. Etymology

The origin of the name "Malta" is uncertain, with the modern term derived from the Maltese word Malta. The most common etymological theory suggests that the name originates from the Greek word {{lang|grc|μέλι|meli|honey}}. The ancient Greeks referred to the island as ΜελίτηMelítēGreek, Ancient, meaning "honey-sweet", possibly due to Malta's unique production of honey from an endemic subspecies of bees. The Romans later called the island Melita, which could be a Latinisation of the Greek Μελίτη or an adaptation of the Doric Greek pronunciation of the same word.

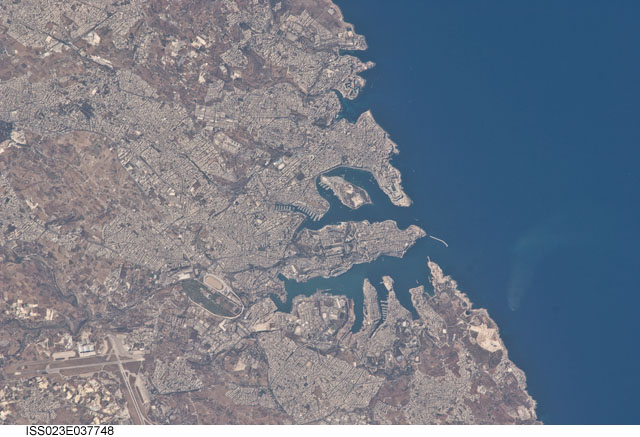

Another conjecture posits that "Malta" derives from the Phoenician word Maleth, meaning "haven" or "port," in reference to Malta's numerous bays and harbors, particularly the Grand Harbour and its primary settlement at Cospicua following a sea-level rise that flooded earlier coastal settlements around the 10th century BC. This name was then applied to the entire island of Malta by the Greeks and to its ancient capital at Mdina (then Melita) by the Romans. The term Malta also appears in its current form in the Antonine Itinerary.

The English name Malta and its demonym Maltese are attested from the late 16th century. English Bible translations, including the 1611 King James Version, long used the Vulgate Latin form Melita, although the 1525 Tyndale Bible used the transliteration Melite. More recent versions widely use Malta.

3. History

Malta's history is a long and rich tapestry woven from the threads of numerous civilizations that have occupied or influenced the islands due to their strategic position in the Mediterranean. From prehistoric temple builders to modern independence and EU membership, Malta has undergone significant transformations, reflecting its role as a cultural and political crossroads.

3.1. Prehistory

Malta has been inhabited since approximately 5900 BC, with the arrival of settlers originating from European Neolithic agriculturalists, likely from Sicily. Pottery found at the Skorba Temples resembles that found in Italy, suggesting these early inhabitants were Stone Age farmers or hunters. The earliest arrivals have been linked to the extinction of endemic dwarf elephants, dwarf hippos, and giant swans. Prehistoric farming settlements dating to the Early Neolithic include Għar Dalam. These early Maltese grew cereals, raised livestock, and, in common with other ancient Mediterranean cultures, worshipped a fertility figure.

Around 3600-3500 BC, a culture of megalithic temple builders emerged, either supplanting or arising from this early period. These people constructed some of the oldest existing free-standing structures in the world, such as the Ġgantija temples on Gozo. Other significant temple complexes include Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra. These temples, used from 4000 to 2500 BC, feature distinctive architecture, typically a complex trefoil design. Archaeological evidence, including statues now in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta, suggests that animal sacrifices were made to a goddess of fertility. The Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum, an underground sanctuary and necropolis, dates from this period. Another notable prehistoric feature is the "cart ruts" (or "cart tracks"), equidistant uniform grooves found in several locations, with the most prominent at Misraħ Għar il-Kbir. These are thought to have been caused by wooden-wheeled carts eroding the soft limestone. This temple culture apparently disappeared from the Maltese Islands around 2500 BC, possibly due to famine, disease, or environmental degradation caused by intensive agriculture.

After 2500 BC, the Maltese Islands were depopulated for several decades until an influx of Bronze Age immigrants arrived. This new culture cremated its dead and introduced smaller megalithic structures called dolmens, which are presumed to have been brought from Sicily due to their similarity to constructions found there.

3.2. Antiquity

Phoenician traders colonized the Maltese islands, possibly naming them Ann (𐤀𐤍𐤍ʾnnPhoenician), sometime after 1000 BC, establishing them as an outpost on their trade routes from the eastern Mediterranean Sea to Cornwall. Their main settlement was likely at Mdina, with the primary port at Cospicua in the Grand Harbour, which they called Maleth. After the fall of Phoenicia in 332 BC, the area came under the control of Carthage, a former Phoenician colony. During this period, the Maltese cultivated olives and carob and produced textiles.

During the First Punic War, Malta was briefly conquered by Marcus Atilius Regulus but returned to Carthaginian control. In 218 BC, during the Second Punic War, the Roman consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus conquered the islands. Malta became a Foederata Civitas, a designation that exempted it from paying tribute and Roman law, falling under the jurisdiction of the province of Sicily. The capital at Mdina was renamed Melita. Punic influence remained strong, as evidenced by the Cippi of Melqart, which were crucial in deciphering the Punic language. Local Roman coinage, which ceased in the first century BC, bore inscriptions in Ancient Greek and Punic motifs, indicating the slow pace of Romanisation.

In the 2nd century AD, Emperor Hadrian upgraded Malta's status to a municipium (free town). Local affairs were administered by four quattuorviri iuri dicundo and a municipal senate, while a Roman procurator in Mdina represented the proconsul of Sicily. In AD 60, according to the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 28), Saint Paul and Luke the Evangelist were shipwrecked on an island named Melite (ΜελίτηGreek, Ancient), widely identified as Malta. Paul is said to have remained for three months, preaching the Christian faith and performing miracles, laying the foundations for Christianity in Malta.

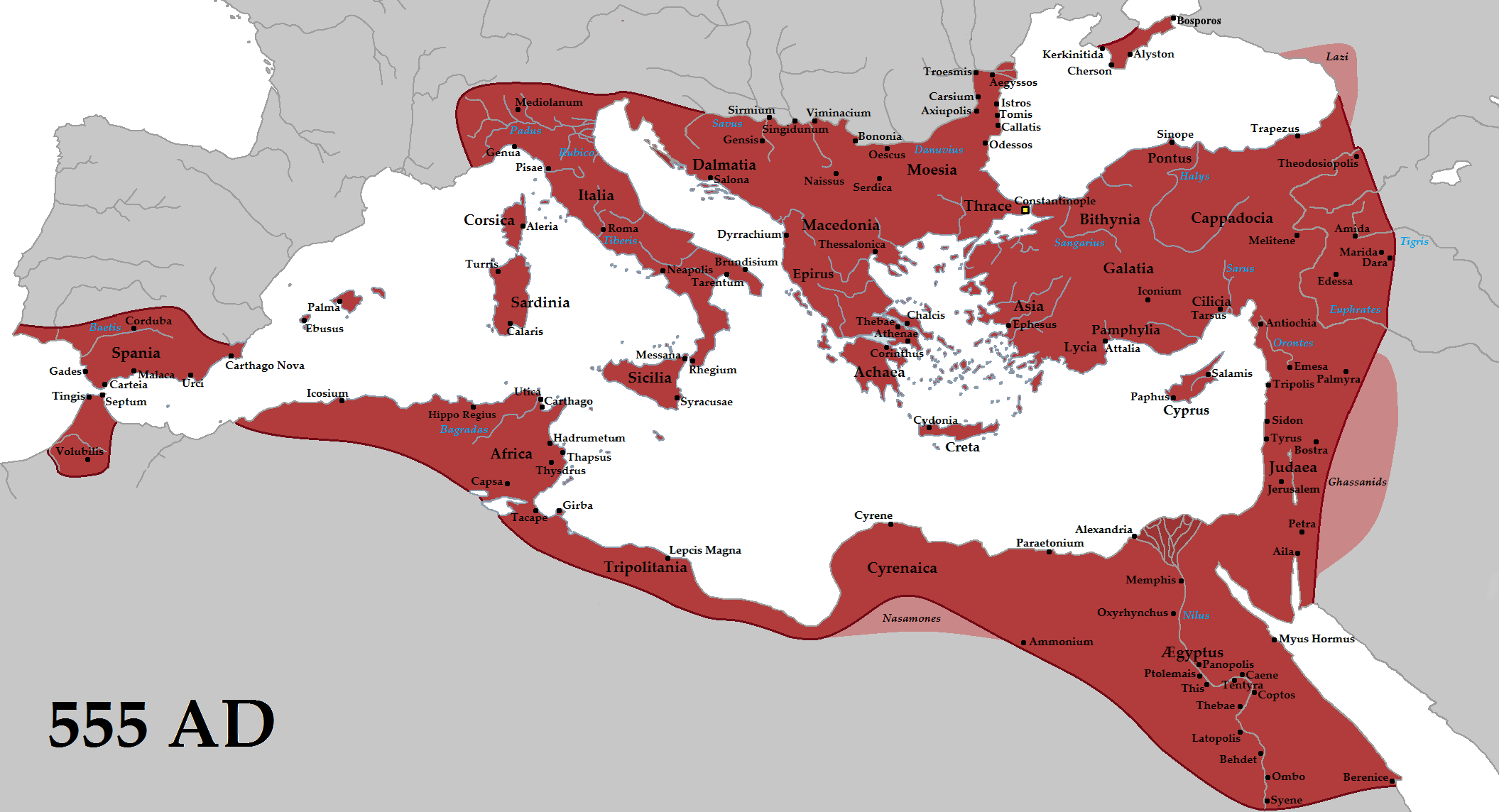

When the Roman Empire was divided in AD 395, Malta, following Sicily, fell under the control of the Western Roman Empire. During the Migration Period, Malta was conquered by the Vandals from 454 to 464 and then by the Ostrogoths. In 533, Belisarius, on his way to conquer the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa, reunited the islands under Imperial (Byzantine or Eastern Roman) rule. Little is known about Byzantine rule in Malta; the island was part of the Theme of Sicily and had Greek governors and a small Greek garrison. While the bulk of the population remained Latinized, Greek families were introduced, and religious allegiance oscillated between the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople. Malta remained under Byzantine rule until 870 when it was conquered by the Arabs.

3.3. Middle Ages

Malta became involved in the Arab-Byzantine wars. In 870, Arab invaders, led first by Halaf al-Hadim and later by Sawada ibn Muhammad, conquered Malta from the Byzantines after a violent struggle. According to the Muslim chronicler al-Himyari, the Arabs pillaged the island, destroyed its important buildings, and left it practically uninhabited. It was recolonised by Muslims from Sicily in 1048-1049. This new settlement may have resulted from demographic expansion in Sicily, a higher standard of living there, or a civil war among Arab rulers in Sicily.

The Arab period brought significant changes. The Arab Agricultural Revolution introduced new irrigation techniques, cotton, and various fruits. The Siculo-Arabic language was adopted from Sicily and gradually evolved into the Maltese language. This linguistic heritage remains a core part of Maltese identity, making Maltese the only Semitic language native to Europe and written in the Latin script.

The Normans, as part of their conquest of Sicily, attacked Malta in 1091. Led by Roger I of Sicily, they were welcomed by Christian captives. Malta became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Sicily, which also covered Sicily and the southern Italian Peninsula. The Catholic Church was reinstated as the state religion, with Malta under the See of Palermo. Some Norman architecture emerged, particularly in the ancient capital of Mdina. King Tancred made Malta a fief of the kingdom and installed a Count of Malta in 1192. The islands' strategic importance led to the militarisation of its male population.

The kingdom passed to the Hohenstaufen dynasty from 1194. Emperor Frederick II initiated a reorganisation of his Sicilian kingdom, leading to a stronger Western cultural and religious influence. Malta was declared a county and a marquisate, but its trade suffered. A mass expulsion of Arabs occurred in 1224, and the entire Christian male population of Celano in Abruzzo was deported to Malta in the same year. In 1249, Frederick II decreed that all remaining Muslims be expelled or compelled to convert, effectively ending the Muslim presence on the island, although the cultural and linguistic impact of the Arab period remained profound. For a brief period, the kingdom passed to the Capetian House of Anjou, but high taxes and Charles of Anjou's war against Genoa made the dynasty unpopular, and Gozo was sacked in 1275.

3.4. Crown of Aragon, the Knights of Malta and Portuguese Rule

Malta was ruled by the House of Barcelona, the ruling dynasty of the Crown of Aragon, from 1282 to 1409, following the Sicilian Vespers in which Aragonese forces aided Maltese insurgents in a naval battle in the Grand Harbour in 1283. Relatives of the kings of Aragon ruled the island until 1409 when it formally passed to the Crown of Aragon. During this period, much of the local nobility was created. By 1397, the title of Count of Malta reverted to a feudal basis, leading to disputes. King Martin I abolished the title, but it was later reinstated. The Maltese, led by local nobility, rose up against Count Gonsalvo Monroy. Impressed by their loyalty to the Sicilian Crown, King Alfonso V of Aragon did not punish the rebellion but instead promised never to grant the title to a third party and incorporated it back into the crown. The city of Mdina was given the title of Città Notabile (Notable City).

On 23 March 1530, Emperor Charles V granted the Maltese islands to the Knights Hospitaller (also known as the Order of St. John and later the Knights of Malta) in perpetual lease. The Knights, under the leadership of Grand Master Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, had been driven out of Rhodes by the Ottoman Empire in 1522. The annual tribute for Malta was a single Maltese Falcon.

The Knights Hospitaller ruled Malta and Gozo from 1530 to 1798. During their rule, Malta's strategic and military importance grew significantly. The Knights' fleet launched attacks from their new base, targeting Ottoman shipping lanes. In 1551, the island of Gozo suffered a devastating raid by Barbary pirates, and its population of around 5,000 people was enslaved and taken to the Barbary Coast.

The defining moment of the Knights' rule was the Great Siege of Malta in 1565. The Knights, led by Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette, along with Maltese forces and support from Spanish and Portuguese forces, withstood a massive Ottoman invasion for nearly four months. The Ottoman defeat was a significant event in checking Ottoman expansion in the Mediterranean. After the siege, the Knights extensively fortified the islands, particularly the harbour area. They built the new capital city, Valletta, named in honour of Grand Master de Valette. Coastal watchtowers - the Wignacourt towers, Lascaris towers, and De Redin towers - were also constructed. The Knights undertook numerous architectural and cultural projects, embellishing Birgu (Città Vittoriosa) and constructing new cities like Ħaż-Żebbuġ (Città Rohan). St. John's Co-Cathedral in Valletta became a masterpiece of Baroque art, notably featuring Caravaggio's "The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist." However, by the late 18th century, the Knights' power had declined, and the Order became unpopular with the Maltese population.

3.5. French occupation and British conquest

The rule of the Knights of St. John ended in 1798 when Napoleon Bonaparte, on his way to Egypt during the French Revolutionary Wars, captured Malta. Napoleon resided at the Palazzo Parisio in Valletta from 12 to 18 June 1798. During his brief stay, he reformed national administration, creating a Government Commission, twelve municipalities, and a public finance administration. He abolished all feudal rights and privileges, abolished slavery, and granted freedom to all Turkish and Jewish slaves. A family code was framed, twelve judges were nominated, and public education was organised. Napoleon then sailed for Egypt, leaving a substantial garrison.

The French forces soon became unpopular with the Maltese, primarily due to their hostility towards Catholicism, the pillaging of churches to fund war efforts, and financial policies. The Maltese rebelled, forcing the French garrison to retreat into Valletta and the harbour fortifications. Great Britain, along with the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily, sent ammunition and aid. The British Royal Navy blockaded the islands.

On 28 October 1798, Captain Sir Alexander Ball negotiated the surrender of the French garrison on Gozo, transferring the island to the British, who then handed it to the locals. Gozo remained independent under Archpriest Saverio Cassar on behalf of Ferdinand III of Sicily until Cassar was removed by the British in 1801.

General Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois surrendered the remaining French forces in Malta in 1800. Maltese leaders presented the main island to Sir Alexander Ball, requesting that it become a British Dominion. The Maltese people created a Declaration of Rights, agreeing to come "under the protection and sovereignty of the King of the free people, His Majesty the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland." The Declaration also stated that "his Majesty has no right to cede these Islands to any power...if he chooses to withdraw his protection, and abandon his sovereignty, the right of electing another sovereign, or of the governing of these Islands, belongs to us, the inhabitants and aborigines alone, and without control."

3.6. British Empire and World War II

In 1814, under the Treaty of Paris, Malta officially became part of the British Empire. It served as a key shipping way-station and naval fleet headquarters. After the Suez Canal opened in 1869, Malta's strategic position halfway between the Strait of Gibraltar and Egypt made it a vital stop on the route to India. A Turkish Military Cemetery was commissioned by Sultan Abdülaziz and built between 1873 and 1874 for Ottoman soldiers who died during the Great Siege or as prisoners of war.

During World War I (1915-1918), Malta became known as the "Nurse of the Mediterranean" due to the large number of wounded soldiers treated there. On 7 June 1919, the Maltese public rioted in response to a cost-of-living crisis and political frustrations; British troops suppressed the riots, killing four Maltese. This event, known as Sette Giugno ("7 June"), is commemorated annually as one of Malta's National Days. Until World War II, Maltese politics was dominated by the Language Question, a struggle between pro-Italian (Italophone) and pro-British (Anglophone) parties regarding the official status of Italian and Maltese.

Before World War II, Valletta was the headquarters of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet. However, despite Winston Churchill's objections, the command was moved to Alexandria, Egypt, in 1937 due to concerns about Malta's vulnerability to air attacks from Europe. During the war, Malta played a crucial role for the Allies. Situated close to Sicily and Axis shipping lanes, Malta was heavily bombarded by Italian and German air forces in what became known as the Second Siege of Malta. The island served as a British base for launching attacks on the Italian Navy and hosted a submarine base. It was also a vital listening post, intercepting German radio messages, including Enigma traffic.

The bravery of the Maltese people during this siege moved King George VI to award the George Cross to Malta on a collective basis on 15 April 1942 "to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history." A depiction of the George Cross now appears on the national flag and the coat of arms. Some historians argue that the award led Britain to incur disproportionate losses in defending Malta, as British credibility would have suffered if Malta had surrendered, similar to the fall of Singapore.

3.7. Independence and Republic

Malta achieved its independence as the State of Malta on 21 September 1964. Under its 1964 constitution, Malta initially retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta and thus head of state, with a governor-general exercising executive authority on her behalf. In 1971, the Malta Labour Party, led by Dom Mintoff, won the general elections. This led to Malta declaring itself a republic on 13 December 1974 (Republic Day) within the Commonwealth of Nations, with a Maltese president as head of state.

A defence agreement signed soon after independence was re-negotiated in 1972 and expired on 31 March 1979 (Freedom Day). Upon its expiry, the British military base closed, and lands formerly controlled by the British were transferred to the Maltese government. Malta adopted a policy of neutrality in 1980 and intensified its participation in the Non-Aligned Movement.

In 1980, three of Malta's sites, including the capital Valletta, the Megalithic Temples of Malta, and the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum, were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. In 1989, Malta hosted the Malta Summit between US President George H. W. Bush and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, their first face-to-face encounter, which is widely regarded as signalling the end of the Cold War.

Malta International Airport was inaugurated and became fully operational on 25 March 1992, boosting the local aviation and tourism industries. A referendum on joining the European Union was held on 8 March 2003, with 53.65% voting in favour. Malta joined the European Union on 1 May 2004, and subsequently joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2008, adopting the Euro as its currency. Valletta was also the first World Heritage City in Europe to become a European Capital of Culture in 2018.

4. Geography

Malta is an archipelago in the central Mediterranean Sea, located about 50 mile (80 km) south of Sicily, Italy, across the Malta Channel. The country consists of three main inhabited islands: Malta (the largest), Gozo (GħawdexMaltese), and Comino (KemmunaMaltese), along with smaller uninhabited islets such as Cominotto, Filfla, and the St. Paul's Islands. The total land area is approximately 122 mile2 (316 km2). The islands of the archipelago lie on the Malta plateau, a shallow shelf formed from the high points of a land bridge that once connected Sicily to North Africa and became isolated as sea levels rose after the last Ice Age. The archipelago is located on the African tectonic plate, though Malta has been considered an island of North Africa for centuries by some. The seabed surrounding Malta's islands retains traces of ancient geomarine features, suggesting potential archaeological discoveries.

The coastline of the Maltese islands is indented with numerous bays and harbors, which have historically been important for maritime activities. The landscape is characterized by low hills and terraced fields. The highest point in Malta is Ta' Dmejrek, at 830 ft (253 m) above sea level, located near Dingli on Malta island. There are no permanent rivers or lakes on Malta, although some small watercourses may form during periods of high rainfall. Freshwater sources are limited, primarily relying on groundwater and desalination. Phytogeographically, Malta belongs to the Liguro-Tyrrhenian province of the Mediterranean region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, Malta's territory belongs to the terrestrial ecoregion of Tyrrhenian-Adriatic sclerophyllous and mixed forests.

The uninhabited minor islands and rocks that are part of the archipelago include:

- Barbaġanni Rock (Gozo)

- Cominotto (KemmunettMaltese)

- Dellimara Island (Marsaxlokk)

- Filfla (near Żurrieq/Siġġiewi)

- Fessej Rock

- Fungus Rock (Il-Ġebla tal-ĠeneralMaltese), (Gozo)

- Għallis Rock (Naxxar)

- Ħalfa Rock (Gozo)

- Large Blue Lagoon Rocks (Comino)

- St. Paul's Islands/Selmunett Island (Mellieħa)

- Manoel Island (connected to Gżira by a bridge, though largely developed)

- Mistra Rocks (San Pawl il-Baħar)

- Taċ-Ċawl Rock (Gozo)

- Qawra Point/Ta' Fraben Island (San Pawl il-Baħar)

- Small Blue Lagoon Rocks (Comino)

- Sala Rock (Żabbar)

- Xrobb l-Għaġin Rock (Marsaxlokk)

- Ta' taħt il-Mazz Rock

4.1. Climate

Malta has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa), characterized by mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. Rain occurs mainly in autumn and winter, with summer being generally dry. Inland areas can experience hotter temperatures during the summer.

The average yearly temperature is around 73.4 °F (23 °C) during the day and 59.9 °F (15.5 °C) at night. In the coldest month, January, the typical maximum temperature ranges from 53.6 °F (12 °C) to 64.4 °F (18 °C), and the minimum from 42.8 °F (6 °C) to 53.6 °F (12 °C). In the warmest month, August, the typical maximum temperature ranges from 82.4 °F (28 °C) to 93.2 °F (34 °C), and the minimum from 68 °F (20 °C) to 75.2 °F (24 °C). Valletta, Malta's capital, has the warmest winters among all capitals in Europe, with average temperatures of around 59 °F (15 °C) to 60.8 °F (16 °C) during the day and 48.2 °F (9 °C) to 50 °F (10 °C) at night in January and February. In March and December, average temperatures are around 62.6 °F (17 °C) during the day and 51.8 °F (11 °C) at night. Large temperature fluctuations are rare. Snow is very rare, although snowfalls have been recorded, with the last significant event in 2014.

The average annual sea temperature is 68 °F (20 °C), ranging from 59 °F (15 °C)-60.8 °F (16 °C) in February to 78.8 °F (26 °C) in August. For six months, from June to November, the average sea temperature exceeds 68 °F (20 °C).

The annual average relative humidity is high, averaging 75%, ranging from 65% in July (morning: 78%, evening: 53%) to 80% in December (morning: 83%, evening: 73%).

Sunshine duration totals around 3,000 hours per year, from an average of 5.2 hours per day in December to over 12 hours per day in July. This is about double that of cities in the northern half of Europe; for instance, London receives about 1,461 hours. In winter, Malta has up to four times more sunshine; London has about 37 hours of sunshine in December, while Malta has over 160 hours.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) | 26.7 (80.1) | 33.5 (92.3) | 30.7 (87.3) | 35.3 (95.5) | 40.1 (104.2) | 42.7 (108.9) | 43.8 (110.8) | 37.4 (99.3) | 34.5 (94.1) | 28.2 (82.8) | 24.3 (75.7) | 43.8 (110.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.7 disp=output number only | 15.7 disp=output number only | 17.4 disp=output number only | 20 disp=output number only | 24.2 disp=output number only | 28.7 disp=output number only | 31.7 disp=output number only | 32 disp=output number only | 28.6 disp=output number only | 25 disp=output number only | 20.8 disp=output number only | 17.2 disp=output number only | 23.1 disp=output number only |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 disp=output number only | 12.6 disp=output number only | 14.1 disp=output number only | 16.4 disp=output number only | 20.1 disp=output number only | 24.2 disp=output number only | 26.9 disp=output number only | 27.5 disp=output number only | 24.9 disp=output number only | 21.8 disp=output number only | 17.9 disp=output number only | 14.5 disp=output number only | 19.5 disp=output number only |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.1 disp=output number only | 9.5 disp=output number only | 10.9 disp=output number only | 12.8 disp=output number only | 15.8 disp=output number only | 19.6 disp=output number only | 22.1 disp=output number only | 23 disp=output number only | 21.2 disp=output number only | 18.4 disp=output number only | 14.9 disp=output number only | 11.8 disp=output number only | 15.9 disp=output number only |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) | 1.7 (35.1) | 2.2 (36.0) | 4.4 (39.9) | 8.0 (46.4) | 12.6 (54.7) | 15.5 (59.9) | 15.9 (60.6) | 13.2 (55.8) | 8.0 (46.4) | 5.0 (41.0) | 3.6 (38.5) | 1.4 (34.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 79.3 frac=1 | 73.2 frac=1 | 45.3 frac=1 | 20.7 frac=1 | 11 frac=1 | 6.2 frac=1 | 0.2 frac=1 | 17 frac=1 | 60.7 frac=1 | 81.8 frac=1 | 91 frac=1 | 93.7 frac=1 | 580.7 frac=1 |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.0 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 8.7 | 10.0 | 61 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 79 | 79 | 77 | 74 | 71 | 69 | 73 | 77 | 78 | 77 | 79 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169.3 | 178.1 | 227.2 | 253.8 | 309.7 | 336.9 | 376.7 | 352.2 | 270.0 | 223.8 | 195.0 | 161.2 | 3,054 |

4.2. Urbanisation

According to Eurostat, Malta is composed of two Larger Urban Zones (LUZs) nominally referred to as "Valletta" (covering the entire main island of Malta) and "Gozo". The main urban area on the island of Malta has a population of around 400,000, with the core of this urban area, the "greater city" of Valletta, having a population of 205,768. More recent Eurostat data from 2020 indicates that the Functional Urban Area and metropolitan region encompasses the whole island of Malta, with a population of 480,134.

The United Nations estimates that about 95 percent of Malta's area is urban, and this figure continues to grow annually. Studies by ESPON and the EU Commission have concluded that "the whole territory of Malta constitutes a single urban region." Given its area of 122 mile2 (316 km2) and a population exceeding half a million, Malta is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. It is often described in various sources as a city-state and is sometimes included in rankings concerning cities or metropolitan areas. This high level of urbanisation presents challenges for infrastructure, housing, and environmental management, requiring careful planning to balance development with the preservation of Malta's natural and historical heritage.

4.3. Flora

Malta's flora is characteristic of the Mediterranean region, adapted to its climate of hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. The islands contain approximately 1.8 mile2 (4.6 km2) of naturally regenerating forest, characterized by mature trees typically 2 to 5 meters in height. The total area occupied by trees is estimated at 124 mile2 (320 km2), which is about 1.44% of the archipelago's total land area.

Common indigenous tree species include the willow, poplar, olive, carob, holm oak (Quercus ilex & Quercus rotundifolia), Aleppo pine, laurel, and fig tree. Common non-native trees include eucalyptus, acacia, date palm, and prickly pear (opuntia).

The Maltese islands are also home to a diverse range of indigenous, sub-endemic, and endemic plants. Endemic plants, found exclusively in Malta, include the national flower, the Maltese centaury (Widnet il-BaħarMaltese; Cheirolophus crassifolius), the Maltese everlasting (sempreviva ta' MaltaMaltese; Helichrysum panormitanum subsp. melitense), the Gozo hyoseris (żigland t' GħawdexMaltese; Hyoseris frutescens), and the Maltese stock (ġiżi ta' MaltaMaltese; Matthiola incana subsp. melitensis). Sub-endemic species, found in Malta and nearby regions, include the Maltese sea chamomile (kromb il-baħarMaltese; Jacobaea maritima subsp. sicula) and the Maltese savory (xkattapietraMaltese; Micromeria microphylla).

The biodiversity of Malta, including its unique flora, faces significant threats from habitat loss due to urban development and agriculture, the introduction of invasive species, and other human interventions. Conservation efforts are crucial to protect these native plant communities.

5. Politics

Malta is a parliamentary republic whose political system and public administration are closely modeled on the Westminster system. The Constitution of Malta is the supreme law of the land. The Parliament of Malta is unicameral, consisting of the President of Malta and the House of Representatives (Kamra tad-DeputatiMaltese).

The President of Malta is the head of state, a largely ceremonial position, appointed for a five-year term by a resolution of the House of Representatives carried by a simple majority. The current president is Myriam Spiteri Debono, who was elected on 27 March 2024. The Prime Minister of Malta is the head of government. According to Article 80 of the Constitution, the president appoints as prime minister "the member of the House of Representatives who, in his judgment, is best able to command the support of a majority of the members of that House". The current prime minister is Robert Abela of the Labour Party, who has been in office since 13 January 2020.

The House of Representatives typically consists of 65 members, elected for a five-year term from 13 five-seat electoral divisions, known as distretti elettoraliMaltese. Members are elected by direct universal suffrage through the single transferable vote system. Constitutional amendments allow for mechanisms to establish strict proportionality between the seats and votes of political parties represented in parliament, which can result in additional seats being awarded. Malta has historically had one of the highest voter turnout rates in the world among nations without mandatory voting.

Maltese politics is predominantly a two-party system, dominated by the centre-left Labour Party (Partit LaburistaMaltese), a social democratic party, and the centre-right Nationalist Party (Partit NazzjonalistaMaltese), a Christian democratic party. The Labour Party has been the governing party since 2013. While there are smaller political parties, they currently hold no parliamentary representation.

In recent years, issues of governance, corruption, and money laundering have been prominent in Maltese political discourse. Transparency International has noted a decline in Malta's performance in tackling corruption since 2013. The assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in 2017, who investigated corruption, brought these issues to international attention and highlighted challenges to the rule of law and press freedom, prompting calls for reforms and greater accountability.

5.1. Administrative divisions

Malta has had a system of local government since 1993, based on the European Charter of Local Self-Government. The country is divided into six regions (Gozo Region, Northern Region, Eastern Region, Port Region, Southern Region, and Western Region). Each region has its own Regional Council, which serves as an intermediate level between local government and the national government.

The regions are further subdivided into 68 local councils (kunsilli lokali), with 54 on the island of Malta and 14 on Gozo. Each local council is made up of a number of councillors (ranging from 5 to 13, depending on the population they represent), elected every five years through the single transferable vote system. A mayor and a deputy mayor are elected by and from the councillors. The executive secretary, appointed by the council, is the executive, administrative, and financial head of the council.

Local councils are responsible for the general upkeep and embellishment of their locality, including repairs to non-arterial roads, allocation of local wardens, and refuse collection. They also carry out general administrative duties for the central government, such as collecting government rents and funds, and answering government-related public inquiries. The six statistical districts (five on Malta island and the sixth being Gozo) serve primarily statistical purposes for data collection by bodies like Eurostat. Many towns and villages in Malta also have twin towns and sister cities internationally.

5.2. Military

The Armed Forces of Malta (AFM) is the military organisation responsible for the defense of the Maltese islands' integrity, as set by the government. Its primary roles include maintaining Malta's territorial waters and airspace integrity, combating terrorism, fighting illicit drug trafficking, conducting anti-illegal immigrant operations and patrols, and anti-illegal fishing operations. The AFM also operates search and rescue (SAR) services within Malta's extensive search-and-rescue area, which covers approximately 97 K mile2 (250.00 K km2) of the central Mediterranean, extending from east of Tunisia to west of Crete.

As a military organization, the AFM provides backup support to the Malta Police Force (MPF) and other government departments and agencies in situations such as national emergencies (like natural disasters), internal security, and bomb disposal. The AFM consists of a headquarters and several units, including an infantry regiment, a maritime squadron, an air wing, and support units. Malta adheres to a policy of neutrality, and its military focuses on territorial defense, maritime security, and contributions to international stability and peacekeeping efforts when appropriate.

In 2020, Malta signed and ratified the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, underscoring its commitment to international peace and disarmament.

5.3. Human rights

Malta has made significant strides in human rights, particularly in recent years, though challenges remain. The Constitution of Malta guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms, including freedom of conscience, expression, assembly, and religion.

Malta is widely regarded as one of the most LGBT-supportive countries in the world. It was the first nation in the European Union to prohibit conversion therapy. Same-sex marriage was legalized in 2017, and laws allowing for gender identity recognition are comprehensive. The country consistently ranks highly on ILGA-Europe's Rainbow Map, which assesses the legal and policy situation for LGBTI people in Europe.

Freedom of religion is protected, with Roman Catholicism recognized as the state religion. The rights of persons with disabilities are also constitutionally protected, with legislation like the Equal Opportunities (Persons with Disability) Act aiming to ensure non-discrimination and promote inclusion.

Abortion in Malta remains illegal, making Malta one of the few EU member states with a near-total ban on the procedure. There are no exceptions for rape or incest. In June 2023, a bill was passed allowing for the termination of a pregnancy if the woman's life is at immediate risk, a limited reform that followed considerable public and political debate. This issue continues to be a significant point of contention, reflecting deep societal divisions.

The rights of migrants and asylum seekers are another critical area. Malta, due to its geographical location, has been a frontline state for migration from Africa to Europe. Irregular migrants arriving by sea are subject to processing, and concerns have been raised by NGOs and international bodies regarding detention conditions and the timeliness of asylum procedures. The European Court of Human Rights has, in some cases, found Malta in breach of its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights concerning the detention of migrants. Amnesty International has also criticized Malta for its tactics in the Mediterranean. The government has emphasized its efforts to manage migration flows while respecting human rights, often calling for greater EU solidarity.

The assassination of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in 2017 highlighted serious concerns about press freedom and the safety of journalists. Subsequent inquiries and international scrutiny have led to calls for reforms to strengthen the rule of law and protect journalists. While blasphemy laws were abolished in 2016, some reports still note areas where discrimination against non-religious individuals could occur, although Malta's legal framework generally aligns with EU standards on non-discrimination.

6. Foreign relations

Malta's foreign policy is shaped by its geographical position in the central Mediterranean, its history, its membership in the European Union (EU) and the Commonwealth of Nations, and its constitutionally enshrined neutrality. Key objectives include promoting peace and security in the Mediterranean region, fostering strong ties with European partners, and participating actively in international organizations.

As an EU member since 2004, Malta plays a role in EU decision-making processes and benefits from economic and political integration. It has been a vocal advocate for Mediterranean issues within the EU, particularly concerning migration, maritime security, and relations with North African countries. Malta held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2017.

Malta maintains strong bilateral relationships with many countries, particularly its European neighbors like Italy, and other Mediterranean nations. It has historically good relations with the United Kingdom due to its colonial past and continued Commonwealth membership. Malta also engages with countries in North Africa, including Libya and Tunisia, on issues of mutual interest such as trade, energy, and migration management. The country has sought to act as a bridge between Europe and North Africa.

Malta has been a member of the United Nations since its independence in 1964 and actively participates in various UN agencies and initiatives. It has served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. Its policy of neutrality, adopted in 1980, means it does not participate in military alliances, though it cooperates with NATO through the Partnership for Peace program. This neutrality was notably highlighted during the 1989 Malta Summit between US President George H.W. Bush and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, which symbolized a step towards the end of the Cold War.

Malta's foreign policy also addresses global issues such as climate change, human rights, and sustainable development. The country has been involved in international efforts concerning maritime law, reflecting its status as an island nation with significant maritime interests. Challenges in foreign relations sometimes arise concerning migration, where Malta often calls for more burden-sharing from EU partners, and in balancing its neutrality with evolving geopolitical dynamics.

7. Economy

Malta is classified as an advanced economy by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and has a high-income economy. Its major economic resources are its strategic geographic location, a productive labor force, and its limestone deposits. Malta produces only about 20% of its food needs, has limited freshwater supplies (relying heavily on desalination), and lacks domestic energy sources apart from growing potential for solar energy. The economy is highly dependent on foreign trade, serving as a freight trans-shipment point, manufacturing (especially electronics, pharmaceuticals, and machinery), and tourism. Film production has also become a notable contributor to the economy, with Malta serving as a location for many international films.

In preparation for its EU membership in 2004, Malta privatised several state-controlled firms and liberalised markets, including telecommunications, postal services, shipyards, and the international airport. The country has developed a strong financial services sector, regulated by the Malta Financial Services Authority (MFSA). It has been successful in attracting gaming businesses (iGaming), aircraft and ship registration, credit-card issuing banking licenses, and fund administration. Malta has actively implemented EU Financial Services Directives, attracting alternative asset managers.

Access to biocapacity in Malta is below the world average. In 2016, Malta had 0.6 global hectares of biocapacity per person within its territory, compared to a global average of 1.6 hectares. Maltese residents exhibited an ecological footprint of consumption of 5.8 global hectares of biocapacity per person, indicating a significant biocapacity deficit. This highlights challenges in environmental sustainability.

As of 2015, Malta did not have a property tax, though various transaction taxes apply. Its property market, especially in harbor areas like St. Julian's, Sliema, and Gżira, experienced a boom, with significant price increases for apartments. According to Eurostat data, Maltese GDP per capita stood at 88% of the EU average in 2015, with €21,000.

The National Development and Social Fund, derived from the Individual Investor Programme (a citizenship by investment scheme), became a significant income source for the government, contributing €432 million to the budget in 2018. This scheme, however, faced criticism regarding due diligence and its implications for EU citizenship, leading to reforms and adjustments.

Social aspects of the economy, such as labor rights and social equity, are important. Malta has a tradition of trade unionism. Ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and addressing income inequality are ongoing considerations. Environmental sustainability is also a key challenge, particularly given the high population density and reliance on imported energy, prompting initiatives towards renewable energy and better resource management.

7.1. Banking and finance

The Maltese banking and finance sector is a significant pillar of its economy. The two largest commercial banks are the Bank of Valletta and HSBC Bank Malta. In recent years, digital banks such as Revolut have also gained popularity among the population.

The Central Bank of Malta (Bank Ċentrali ta' MaltaMaltese) is the country's central banking institution. Its key responsibilities include the formulation and implementation of monetary policy (as part of the Eurosystem) and the promotion of a sound and efficient financial system. The Maltese government entered the ERM II on 4 May 2005, and officially adopted the Euro as the country's currency on 1 January 2008, replacing the Maltese lira.

Malta has established itself as an international financial centre, attracting foreign investment and financial institutions. The Malta Financial Services Authority (MFSA) is the single regulator for financial services in Malta, overseeing banking, financial institutions, insurance, investment services, and the stock exchange. The country has leveraged its EU membership and a favorable regulatory environment to develop niches in areas like fund administration, insurance, and, more recently, fintech and blockchain technologies, although the latter has also brought scrutiny regarding regulatory oversight and potential risks. The sector's growth has contributed significantly to Malta's GDP, but it also faces challenges related to international tax harmonisation efforts and ensuring robust anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) frameworks.

7.2. Currency

The official currency of Malta is the Euro (€), which it adopted on 1 January 2008, replacing the Maltese lira (MTL). The decision to join the Eurozone was a significant step in Malta's economic integration with the European Union.

Maltese euro coins feature unique national designs on the obverse side.

- The €2 and €1 coins depict the Maltese cross.

- The €0.50, €0.20, and €0.10 coins feature the Maltese coat of arms.

- The €0.05, €0.02, and €0.01 coins show an image of the altar at the Mnajdra Temples.

Malta also produces collectors' coins in gold and silver, with face values typically ranging from €10 to €50. These coins continue a national tradition of minting commemorative pieces and are legal tender in Malta but are not generally intended for circulation across the Eurozone.

Before the Euro, the Maltese lira (MTL), often abbreviated as Lm, was the currency of Malta from its decimalisation in 1972 until 31 December 2007. The lira itself had replaced the Maltese pound at par in 1972, which had been in use alongside British currency. The Maltese pound had, in turn, replaced the Maltese scudo in 1825.

7.3. Tourism

Tourism is a cornerstone of the Maltese economy, contributing significantly to the country's GDP (around 11.6% directly) and employment. Malta is a popular tourist destination, attracting over 2.1 million tourists in 2019, a figure more than three times its resident population. Key attractions include its warm Mediterranean climate, numerous recreational areas, rich historical and architectural monuments (including three UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Valletta, the Megalithic Temples of Malta, and the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum), and vibrant cultural scene. Popular activities include visiting historical sites, enjoying the beaches and water sports, diving (due to clear waters and interesting wreck sites), and experiencing local festivals and cuisine.

The tourism infrastructure has expanded dramatically over the years, with a wide range of hotels, resorts, and other accommodation options available across the islands, particularly on Malta and Gozo. However, this growth has also led to concerns about overdevelopment, pressure on natural resources (especially water and land), and the impact on traditional housing and landscapes. Efforts are being made to promote more sustainable tourism practices.

In recent years, Malta has also marketed itself as a destination for medical tourism, leveraging its healthcare facilities and English-speaking environment. Other niche tourism segments include English language learning (attracting students from around the world), conference tourism, and, more recently, film tourism, as Malta's diverse locations have been used in numerous international film and television productions. The socio-economic benefits of tourism are substantial, but managing its environmental and social impacts remains an ongoing challenge for the country.

7.4. Science and technology

Malta has been making concerted efforts to develop its science and technology sector as part of its broader economic diversification strategy. The Malta Council for Science and Technology (MCST) is the primary governmental body responsible for advising on science and technology policy, promoting research and innovation, and managing related funding programs.

The country has signed a co-operation agreement with the European Space Agency (ESA), aiming for more intensive collaboration in ESA projects and fostering growth in space-related research and industry within Malta. Initiatives are in place to encourage R&D investment, support startups, and build a skilled workforce in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields.

Most science and technology graduates in Malta come from the University of Malta, which offers a range of programs in these disciplines. Student societies such as S-Cubed (Science Students' Society), UESA (University Engineering Students Association), and ICTSA (University of Malta ICT Students' Association) play a role in representing and supporting students in these fields. The Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology (MCAST) also provides vocational and technical education crucial for the sector.

Malta was ranked 29th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024, indicating a developing capacity for innovation. Areas of focus for technological development include information and communication technology (ICT), digital gaming (iGaming), biotechnology, maritime technology, and renewable energy solutions. The government has also shown interest in emerging technologies like blockchain and artificial intelligence, aiming to position Malta as a hub in these areas, though this has also come with regulatory challenges.

8. Infrastructure

Malta has developed a modern infrastructure to support its dense population and diverse economy, though challenges related to its small size and high density persist.

8.1. Transport

Traffic in Malta drives on the left, a legacy of British colonial rule. Car ownership is exceedingly high, ranking among the highest in the European Union, which contributes to traffic congestion, particularly in urban areas. In 1990, there were 182,254 registered cars, an automobile density of approximately 577 cars per square kilometer (1,493 per square mile). Malta has approximately 1.4 K mile (2.25 K km) of roads, of which about 87.5% were paved as of December 2003.

Buses (xarabankMaltese or karozza tal-linjaMaltese) are the primary mode of public transport. The traditional Maltese buses, many of which were vintage vehicles, operated until 2011 and became a popular tourist attraction. In July 2011, the bus service underwent extensive reform, transitioning from self-employed drivers to a service operated by a single company under public tender. Arriva Malta initially won the tender, introducing a new fleet. However, Arriva ceased operations in Malta on 1 January 2014, due to financial difficulties and was nationalised as Malta Public Transport. In October 2014, Autobuses Urbanos de León (a subsidiary of ALSA) was chosen as the new operator. Since October 2022, the bus system has been free of charge for residents of Malta holding a personalized Tallinja card. As of 2021, a metro system is being planned, with a projected cost of €6.2 billion, aiming to alleviate traffic congestion.

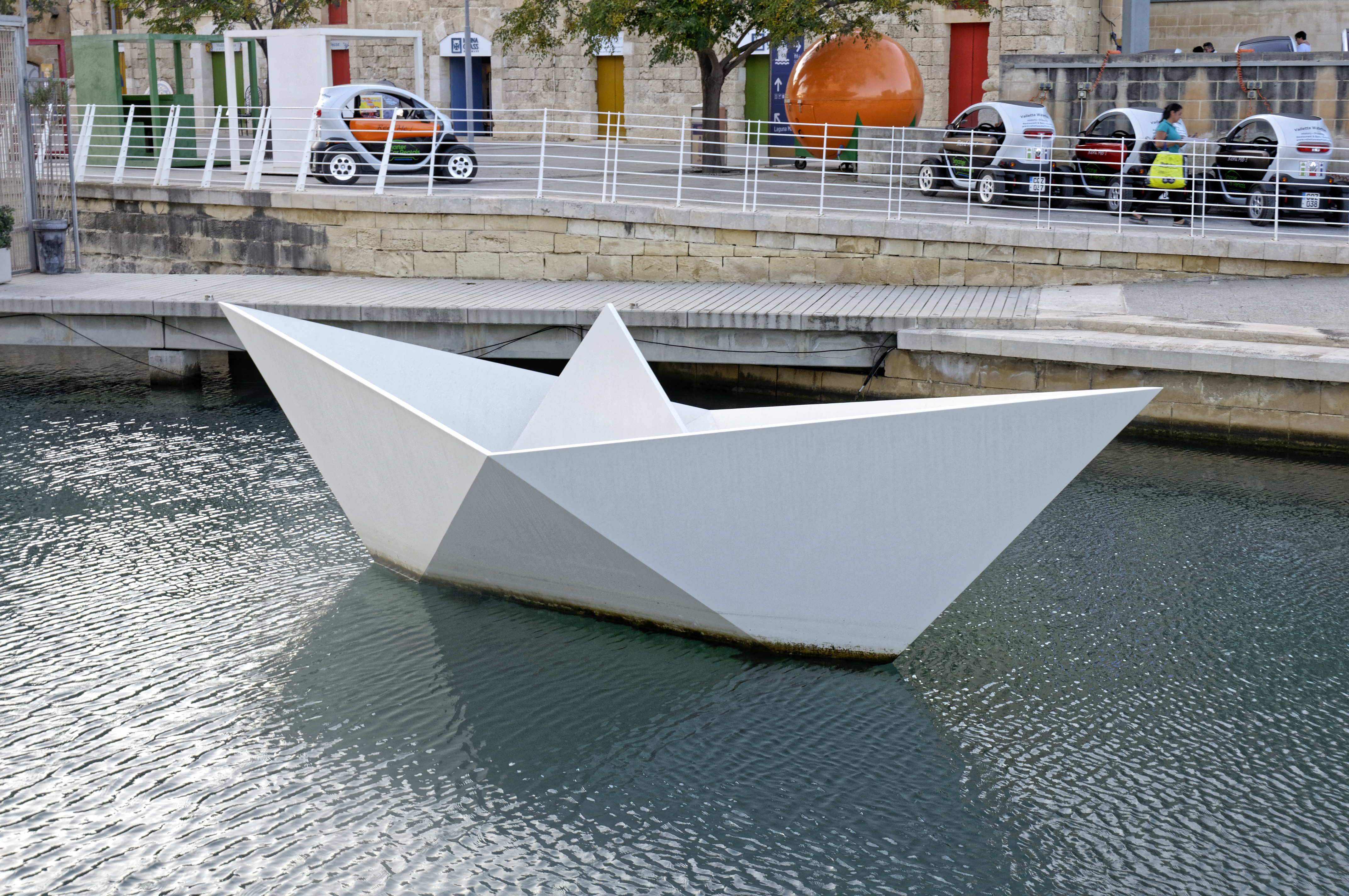

Malta has three large natural harbours on its main island:

- The Grand Harbour (or Port il-Kbir), located east of Valletta, has been a harbour since Roman times. It features extensive docks, wharves, and a cruise liner terminal. Ferries connect Malta to Pozzallo and Catania in Sicily from here.

- Marsamxett Harbour, west of Valletta, accommodates several yacht marinas.

- Marsaxlokk Harbour (Malta Freeport), at Birżebbuġa on the south-eastern side, is the islands' main cargo terminal. Malta Freeport is one of the busiest container ports in Europe and the Mediterranean.

Two man-made harbours, Ċirkewwa Harbour on Malta and Mġarr Harbour on Gozo, serve the passenger and car ferry service connecting the two main islands.

Malta International Airport (Ajruport Internazzjonali ta' MaltaMaltese) is the sole airport serving the Maltese islands, located in Luqa on the site of the former RAF Luqa airbase. It includes a heliport, and there is another heliport at Xewkija on Gozo. The former RAF Ta Kali airfield now houses a national park, stadium, the Crafts Village, and the Malta Aviation Museum.

From 1 April 1974 to 30 March 2024, the national airline was Air Malta, based at Malta International Airport, operating services to destinations in Europe and North Africa. On 31 March 2024, KM Malta Airlines took over as the new national airline, inheriting Air Malta's assets and staff, and currently serves 18 European destinations. In June 2019, Ryanair established a Maltese subsidiary, Malta Air, operating a low-cost model, in which the Government of Malta holds one share.

8.2. Communications

Malta has a well-developed telecommunications infrastructure. The mobile penetration rate exceeded 100% by the end of 2009. The country uses GSM900, UMTS (3G), and LTE (4G) mobile phone systems, which are compatible with those in other European countries, Australia, and New Zealand. Major mobile operators provide extensive coverage across the islands.

Internet accessibility is widespread, with high broadband penetration rates. In early 2012, the government called for a national Fibre to the Home (FTTH) network to be built, aiming to upgrade minimum broadband service speeds significantly, from around 4 Mbit/s to 100 Mbit/s or higher. This initiative has largely been implemented, providing high-speed internet access to most households and businesses.

Public Wi-Fi hotspots are also available in many public areas across Malta and Gozo, enhancing connectivity. The Malta Communications Authority (MCA) regulates the telecommunications sector, ensuring fair competition and consumer protection.

8.3. Energy

Malta's energy sector relies heavily on imported fuels, as the country has no indigenous fossil fuel resources. Historically, Malta depended on coal for electricity generation until 1996. The primary power generation facility is the Delimara Power Station, located in Marsaxlokk. This station initially used heavy fuel oil when a new plant was built in 1992. In 2017, a significant portion of the Delimara Power Station was converted to operate on liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is considered a cleaner fossil fuel. The station also includes two gasoil-fired plants, which are maintained as standby capacity for emergencies or when other power sources are insufficient.

A key development in Malta's energy infrastructure is the Malta-Sicily interconnector, an undersea power cable commissioned in 2015. This interconnector links Malta to the European power grid via Sicily, allowing Malta to import a significant share of its electricity. This has enhanced energy security and provided access to potentially cheaper and cleaner energy from the European market.

Malta is also actively pursuing initiatives to increase its use of renewable energy, primarily solar power, given its abundant sunshine. Incentives for the installation of photovoltaic (PV) panels on residential and commercial buildings have been implemented. However, the share of renewables in the energy mix is still relatively low compared to EU targets, and efforts are ongoing to expand renewable generation capacity, including exploring options for offshore wind energy. Environmental concerns related to energy production, particularly emissions from the power station and reliance on imported fuels, remain a focus of policy.

8.4. Healthcare

Malta has a long history of providing publicly funded health care, with the first hospital recorded in the country functioning by 1372. Today, Malta has a dual healthcare system, comprising both a public healthcare system, where most services are free at the point of delivery for eligible residents, and a private healthcare sector. The public system is funded through general taxation.

The cornerstone of the public healthcare system is a strong general practitioner-delivered primary care base. Secondary and tertiary care are provided by public hospitals, the main one being Mater Dei Hospital, which opened in 2007 and is one of the largest medical buildings in Europe. Other public hospitals include specialised facilities like Sir Anthony Mamo Oncology Centre and Mount Carmel Hospital for mental health. The Maltese Ministry of Health advises foreign residents to take out private medical insurance to cover services not included in the public system or to access private facilities.

Malta also has a growing private healthcare sector, offering a range of medical services, including hospital care, specialist consultations, and diagnostic tests. This sector caters to both local patients seeking faster access or alternative options, and medical tourists.

The University of Malta has a medical school and a Faculty of Health Sciences, providing training for medical professionals. The Medical Association of Malta represents practitioners of the medical profession. To address the issue of newly graduated physicians emigrating, particularly to the British Isles (a phenomenon known as 'brain drain'), Malta has introduced programmes similar to the Foundation Programme followed in the UK.

Voluntary organisations such as Alpha Medical (Advanced Care), the Emergency Fire & Rescue Unit (E.F.R.U.), St John Ambulance, and Red Cross Malta also contribute to healthcare by providing first aid and nursing services during public events and emergencies.

9. Demographics

Malta is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. As of the 2021 census, the total population of the Maltese Islands stood at 519,562. Maltese-born natives make up the majority, numbering 386,280. There are significant minorities, with the largest groups by birthplace being from the United Kingdom (15,082), Italy (13,361), India (7,946), Philippines (7,784), and Serbia (5,935). Among non-Maltese residents, 58.1% identified their racial origin as Caucasian, 22.2% Asian, 6.3% Arab, 6.0% African, 4.5% Hispanic or Latino, and 2.9% as having more than one racial origin.

In 2005, 17% of the population was aged 14 and under, 68% were within the 15-64 age bracket, and 13% were 65 years and over. Malta's population density of over 1,282 per square kilometer (3,322/sq mi) was by far the highest in the EU at that time. The Maltese-resident population in 2004 was estimated to make up 97.0% of the total resident population. All censuses since 1842 have shown a slight excess of females over males. Population growth slowed from +9.5% between the 1985 and 1995 censuses to +6.9% between the 1995 and 2005 censuses (a yearly average of +0.7%). In 2005, the birth rate stood at 3,860 (a decrease of 21.8% from the 1995 census) and the death rate at 3,025, resulting in a natural population increase of 835.

The population's age composition is similar to the age structure prevalent in the EU. Malta's old-age dependency ratio rose from 17.2% in 1995 to 19.8% in 2005, lower than the EU's 24.9% average at the time. 31.5% of the Maltese population was aged under 25 in 2005 (compared to the EU's 29.1%), but the 50-64 age group constituted 20.3% of the population, significantly higher than the EU's 17.9%. The old-age-dependency ratio is expected to continue rising.

The total fertility rate (TFR) as of 2016 was estimated at 1.45 children born per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1. In 2012, 25.8% of births were to unmarried women. The life expectancy in 2018 was estimated at 83 years.

| Racial origin | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Caucasian | 89.1% |

| Asian | 5.2% |

| Arab | 1.7% |

| African | 1.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.3% |

| More than one racial origin | 1.2% |

9.1. Languages

The Maltese language (MaltiMaltese) and English are the two constitutional official languages of Malta. Maltese is also recognized as the national language. Laws are enacted in both Maltese and English; however, Article 74 of the Constitution states that "if there is any conflict between the Maltese and the English texts of any law, the Maltese text shall prevail." Many speakers of English in Malta use a local dialect known as Maltese English.

Maltese is a Semitic language descended from Siculo-Arabic, an extinct dialect of Arabic that developed in Sicily and Malta during the Emirate of Sicily. Its vocabulary has a significant number of loanwords from Italian (particularly Sicilian) and English. The Maltese alphabet is based on the Latin alphabet with the addition of diacriticised letters such as ż, ċ, ġ, ħ, and għ.

According to the Malta National Statistics Office in 2022, 90% of the Maltese population has at least a basic knowledge of Maltese, 96% of English, 62% of Italian, and 20% of French. This widespread knowledge of second languages makes Malta one of the most multilingual countries in the European Union. A study on language preference found that 86% of the population preferred Maltese, 12% English, and 2% Italian. Italian television channels from Italy-based broadcasters like Mediaset and RAI are widely received and remain popular in Malta.

Maltese Sign Language (Lingwa tas-Sinjali MaltijaMaltese, LSM) is used by the deaf community in Malta and was officially recognized in 2016.

9.2. Religion

The predominant religion in Malta is Roman Catholicism. Article 2 of the Constitution of Malta establishes Catholicism as the state religion, and its influence is reflected in various elements of Maltese culture, although the constitution also guarantees freedom of religion and conscience. Malta has more than 360 churches across its islands, roughly one church for every 1,000 residents. The parish church (il-parroċċaMaltese or il-knisja parrokkjaliMaltese) is often the architectural and geographical focal point of Maltese towns and villages.

Malta is an Apostolic See. The Acts of the Apostles (Acts 28) recounts the shipwreck of St. Paul on the island of "Melite" (widely identified as Malta) around AD 60. Saint Publius, said to have been Malta's first bishop, is one of Malta's patron saints, along with St. Paul and Saint Agatha. George Preca (San Ġorġ PrecaMaltese) is highly revered as the second canonised Maltese saint. Early Christian practices are evidenced by catacombs, such as St. Paul's Catacombs, and cave churches, including the grotto at the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Mellieħa. Various Catholic religious orders, including the Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, and Carmelites, are present in Malta.

According to the 2021 census, 82.6% of the population identified as Catholic. Other Christian denominations include Eastern Orthodox Christians (3.6%), Anglicans (1.3%), and other Protestants (1.0%). Islam is practiced by 3.9% of the population. Hinduism is followed by 1.4%, and Buddhism by 0.5%. The Jewish community accounts for 0.3%, and other religious groups comprise 0.04% of the population. Approximately 5.1% of the population reported having no religion in the 2021 census. There are small parishes for Greek, Russian, Serbian, Romanian, and Bulgarian Orthodox communities. Most congregants of local Protestant churches are non-Maltese. There are also small communities of Seventh-day Adventists, New Apostolic Church, Jehovah's Witnesses (approximately 600), and Mormons (around 241 members). One purpose-built mosque, the Mariam Al-Batool Mosque in Paola, serves the Muslim population, which consists of foreigners, naturalised citizens, and some native-born Maltese, though other prayer spaces exist. The Baháʼí Faith and Zen Buddhism also have small followings.

A 2019 Eurobarometer survey reported 83% of the population identified as Catholic. While Malta is deeply religious, the number of atheists and agnostics has reportedly increased. Historically, blasphemy laws existed but were abolished in 2016. Some reports have indicated that non-religious individuals may face societal discrimination, though legal protections are in place.

9.3. Migration

Historically a country of emigration, Malta has experienced a significant increase in net immigration since the early 21st century. The foreign-born population grew nearly eightfold between 2005 and 2020. The foreign community includes active and retired British nationals, often centered around Sliema and surrounding areas, as well as Italians, Libyans, Serbians, and, more recently, workers from India and the Philippines. This immigration was driven by Malta's booming economy and, for a time, relatively stable living costs, although rising housing prices have become a challenge.

| Foreign population in Malta | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % total |

| 2005 | 12,112 | 3.0% |

| 2011 | 20,289 | 4.9% |

| 2019 | 98,918 | 21.0% |

| 2020 | 119,261 | 23.17% |

Since the late 20th century, Malta has become a transit country for migration routes from Africa to Europe. As an EU member and part of the Schengen Area, Malta is bound by the Dublin Regulation to process asylum claims from those who first enter EU territory in Malta. Irregular migrants arriving by sea are subject to a compulsory detention policy in camps managed by the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM). This policy has faced criticism from NGOs and the European Court of Human Rights, which found in 2010 that Malta's detention of migrants was arbitrary and lacked adequate challenge procedures. Amnesty International in 2020 criticized Malta for "illegal tactics" in the Mediterranean against migrants, alleging actions that might have led to avoidable deaths. The Maltese government has emphasized its efforts to manage migration flows while respecting human rights, often calling for greater EU solidarity and burden-sharing.

In January 2014, Malta introduced an Individual Investor Programme (IIP), granting citizenship for a €650,000 contribution plus investments, contingent on residence and background checks. This "golden passport" scheme became a significant revenue source but drew criticism from the European Council and others regarding due diligence, transparency, and the implications of selling EU citizenship. Concerns were raised about allowing individuals with questionable backgrounds into the EU. The scheme has undergone reforms and was eventually phased out and replaced by a new programme with stricter conditions.

Historically, Maltese emigration in the 19th century was mainly to North Africa and the Middle East, with high rates of return. In the 20th century, emigrants predominantly went to the New World, particularly Australia, Canada, and the United States. After World War II, the Maltese Emigration Department assisted emigrants with travel costs. Between 1948 and 1967, about 30% of the population emigrated. Over 140,000 people left Malta under assisted passage schemes between 1946 and the late 1970s, with 57.6% going to Australia, 22% to the UK, 13% to Canada, and 7% to the United States. Emigration significantly decreased after the mid-1970s. Since Malta joined the EU in 2004, expatriate communities have emerged in other European countries, notably Belgium and Luxembourg.

9.4. Education

Education in Malta is compulsory from age 5 to 16 and is largely based on the British model. The state and the Catholic Church both provide education free of charge, running numerous schools across Malta and Gozo. There are also a number of private schools, including international schools like Verdala International School and QSI Malta. The state subsidises a portion of the teachers' salaries in Church schools.

Primary schooling lasts for six years. At age 16, pupils sit for the Secondary Education Certificate (SEC) O-level examinations, with passes generally required in core subjects like mathematics, English, Maltese, and at least one science subject. After O-levels, students may opt to continue their studies at a sixth form college for two years, culminating in the Matriculation Certificate examination. Performance in these exams determines eligibility for undergraduate degree or diploma programs at higher education institutions.

The main higher education institution is the University of Malta, a publicly funded university offering a wide range of courses. The Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology (MCAST) provides vocational and professional education and training. The Institute of Tourism Studies (ITS) focuses on hospitality and tourism education.

The adult literacy rate in Malta is high, at 99.5%. Maltese and English are both used as languages of instruction in primary and secondary schools, and both are compulsory subjects. Public schools tend to use both languages, while private schools often prefer English for teaching. Most university courses are delivered in English. The widespread use of English in higher education and professional settings has had an impact on the functional use of Maltese in some domains.

Of the total number of pupils studying a first foreign language at the secondary level, 51% take Italian, while 38% take French. Other foreign languages offered include German, Russian, Spanish, Latin, Chinese, and Arabic. Malta is also a popular destination for studying English as a foreign language, attracting over 83,000 students in 2019.

10. Culture

The culture of Malta is a rich tapestry reflecting the diverse civilizations that have come into contact with or ruled the Maltese Islands over centuries. This blend of Mediterranean and historical influences, particularly from Italy, North Africa, and Great Britain, has shaped its unique traditions, language, arts, cuisine, and social customs.

10.1. Music

While contemporary Maltese music is largely Western in style, traditional Maltese music includes għana. This folk music form typically features folk guitar accompaniment while individuals, usually men, take turns delivering improvised verses in a sing-song voice, often engaging in a form of lyrical debate or storytelling. Music plays an integral part in Maltese cultural life, especially during village festas (feasts), where local band clubs (każini tal-banda) are central to the celebrations, parading through the streets and providing a festive musical backdrop. Each locality often has more than one band club.

The Malta Philharmonic Orchestra is the country's foremost classical music institution and regularly participates in important state events and international performances. Malta has also produced notable classical musicians, including tenor Joseph Calleja and soprano Miriam Gauci.

In contemporary popular music, Malta has a vibrant scene with various genres. Bands like Winter Moods and Red Electric, and singers such as Ira Losco, Fabrizio Faniello, Glen Vella, Kevin Borg, Kurt Calleja, Chiara Siracusa, and Thea Garrett have gained local and, in some cases, international recognition, particularly through participation in events like the Eurovision Song Contest.

10.2. Literature

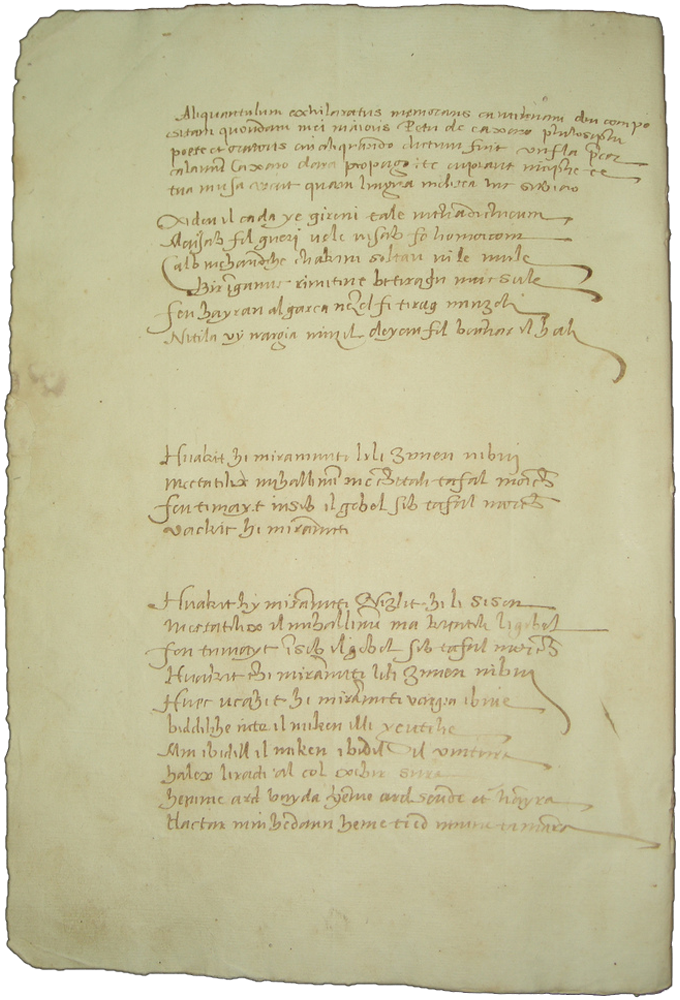

Maltese literature, primarily written in the Maltese language, has a documented history spanning over 200 years, although a recently unearthed love ballad testifies to literary activity in the vernacular from the Medieval period. The development of Maltese as a literary language was significantly advanced by figures like Mikiel Anton Vassalli in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, who worked on standardizing the language.

Malta followed a Romantic literary tradition, which culminated in the works of Dun Karm Psaila (1871-1961), considered Malta's national poet. His poetry, including the lyrics for the Maltese national anthem, played a crucial role in establishing Maltese as a respected literary medium. Subsequent writers, such as poet Ruzar Briffa and playwright and novelist Karmenu Vassallo, sought to explore new themes and move away from the more formal and traditional styles.

The post-World War II period saw a diversification of Maltese literature. Writers like Francis Ebejer (plays and novels), Oliver Friggieri (poetry, novels, literary criticism), and Joe Friggieri (philosophy, short stories, plays) made significant contributions. The next generation of writers, including Karl Schembri and Immanuel Mifsud (who won the European Union Prize for Literature in 2011), further widened the scope of Maltese literature, particularly in prose and poetry, often addressing contemporary social and personal themes. Key literary themes often revolve around Maltese identity, history, religion, emigration, and the complexities of island life. The National Book Council of Malta actively promotes Maltese literature through book fairs and awards.

10.3. Architecture

Maltese architecture is a rich amalgam of styles reflecting its long and varied history, with influences from numerous Mediterranean cultures as well as British colonial architecture.

The earliest significant architectural achievements are the Megalithic Temples of Malta, such as Ġgantija, Ħaġar Qim, and Mnajdra, dating back to 3600-2500 BC. These are some of the oldest man-made freestanding structures in the world and showcase sophisticated construction techniques for their time, featuring intricate stone carvings and monumental scale. The Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum is a unique underground necropolis from the same period.

The Phoenician and Carthaginian periods left fewer monumental remains, but Roman rule introduced classical architecture, including villas with decorative mosaic floors (e.g., the Domvs Romana in Rabat), marble colonnades, and statuary. Early Christian catacombs with frescoes show Byzantine influences.

During the Arab period (870-1091), elements of Islamic architecture were likely introduced, though few direct examples survive, as subsequent Norman and Christian rulers often rebuilt over earlier structures. The Normans brought Romanesque and later Gothic styles, particularly evident in Mdina.

The arrival of the Knights of St. John in 1530 marked a transformative era for Maltese architecture. They introduced Renaissance and, most significantly, Baroque styles. After the Great Siege of 1565, they built the fortified city of Valletta, designed by Francesco Laparelli and continued by Gerolamo Cassar. Valletta is a masterpiece of Baroque urban planning and architecture, with prominent buildings like St. John's Co-Cathedral, the Grandmaster's Palace, and numerous auberges. The fortifications themselves, such as those around Valletta and the Three Cities, are monumental examples of military architecture. Maltese Baroque is characterized by ornate decorations, balconies, and the use of local honey-coloured limestone.

The British colonial period (1800-1964) introduced Neoclassical and various Victorian and Edwardian styles. Notable British-era buildings include theaters, hospitals, and administrative structures, often incorporating verandas and using the local limestone.

Modern and contemporary architecture in Malta has seen the construction of new commercial buildings, hotels, and public projects, sometimes controversially in terms of their impact on the historic urban landscape and environment. There is an ongoing effort to balance new development with the preservation of Malta's rich architectural heritage.

10.4. Art

The art of Malta has been shaped by its strategic Mediterranean location and the succession of cultures that have influenced the islands. Towards the end of the 15th century, Maltese artists, like their Sicilian counterparts, came under the influence of the School of Antonello da Messina, which introduced Renaissance ideals.

The artistic heritage flourished under the Knights of St. John (1530-1798). They brought Italian and Flemish Mannerist painters to decorate their palaces and churches. Notable among them was Matteo Perez d'Aleccio, whose works adorn the Magisterial Palace and St. John's Co-Cathedral in Valletta, and Filippo Paladini.

The arrival of Caravaggio in Malta in 1607-1608, though brief, was a pivotal moment. He painted at least seven works during his 15-month stay, including two masterpieces: The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist and Saint Jerome Writing, both housed in St. John's Co-Cathedral. His dramatic chiaroscuro technique profoundly influenced local artists like Giulio Cassarino and Stefano Erardi.

The Baroque movement had the most enduring impact on Maltese art and architecture. The vault paintings by Calabrian artist Mattia Preti transformed St. John's Co-Cathedral into a Baroque masterpiece. Preti spent a significant part of his career in Malta and produced numerous works for churches and patrons across the island. Maltese sculptor Melchior Gafà (or Caffà) emerged as one of the top Baroque sculptors of the Roman School.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Neapolitan and Rococo influences are seen in the works of Italian painters like Luca Giordano and Francesco Solimena, and their Maltese contemporaries such as Gio Nicola Buhagiar and Francesco Zahra. Antoine de Favray became court painter to Grand Master Pinto in 1744 and introduced French Rococo elegance.

Neoclassicism made some inroads in the late 18th century. In the early 19th century, under British rule, the local Church authorities favoured the religious themes of the Nazarene movement. Romanticism, tempered by the naturalism of Giuseppe Calì, informed early 20th-century "salon" artists like Edward and Robert Caruana Dingli.

The National School of Art was established in the 1920s. After World War II, the "Modern Art Group," including artists like Josef Kalleya, George Preca, Anton Inglott, Emvin Cremona, Frank Portelli, Antoine Camilleri, Gabriel Caruana, and Esprit Barthet, greatly enhanced the local art scene. Contemporary Maltese art is diverse, with many artists having studied abroad. MUŻA (Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti), the National Museum of Art located in Valletta at Auberge d'Italie, houses the national collection of fine arts.

10.5. Cuisine