1. Overview

Nepal, officially known as Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia, primarily situated in the Himalayas but also including parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It is bordered by the Tibet Autonomous Region of China to the north, and India to the south, east, and west. Nepal's geography is diverse, featuring fertile plains, subalpine forested hills, and eight of the world's ten tallest mountains, including Mount Everest. Kathmandu is the capital and largest city. A multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious, and multi-cultural state, Nepali is its official language.

Historically, Nepal has transitioned from ancient civilizations and various dynasties, through a period of unification under the Gorkha Kingdom, and a long era of Rana autocracy. The 20th and early 21st centuries were marked by significant pro-democracy movements, a decade-long civil war, and the eventual abolition of the monarchy in 2008, leading to the establishment of a federal democratic republic. The 2015 constitution affirmed this structure, dividing the country into seven provinces.

Nepal's culture is rich and varied, influenced by its diverse ethnic groups and religions, primarily Hinduism and Buddhism. Traditional arts, architecture, literature, music, and cuisine reflect this diversity. Social structures, including the caste system, have historically shaped Nepalese society, though efforts towards social inclusion and reform are ongoing.

The economy is predominantly agricultural, with tourism being another significant sector. Nepal faces challenges as a least developed country, including poverty, infrastructure deficits, and the impacts of environmental issues such as deforestation and pollution. Overseas labor and remittances play a crucial role in the economy. The nation's political landscape emphasizes democratic development, human rights, and social justice, though challenges in consolidating these aspects persist. Foreign relations are guided by a policy of non-alignment, with close ties to its immediate neighbors, India and China, and reliance on international aid for development.

2. Etymology

The precise origin of the name "Nepal" (नेपालNepālNepali) is uncertain, and various etymological interpretations exist. The name is first recorded in texts from the Vedic period of the Indian subcontinent. Ancient Indian literary texts dated as far back as the fourth century AD mention Nepāl.

According to Hindu mythology, Nepal derives its name from an ancient Hindu sage called Ne, referred to variously as Ne Muni or Nemi. The Pashupati Purāna states that as a place protected by Ne, the country in the heart of the Himalayas came to be known as Nepāl. The word pala in the Pali language means "to protect," thus Nepala could translate to "protected by Ne." The Nepāl Mahātmya claims Nemi was charged with the protection of the country by Pashupati. Buddhist mythology suggests that Manjushri Bodhisattva drained a primordial lake of serpents to create the Nepal valley and proclaimed that Adi-Buddha Ne would take care of the community that would settle it; as the cherished of Ne, the valley would be called Nepāl. According to the Gopalarājvamshāvali, a genealogy of the ancient Gopala dynasty compiled around the 1380s, Nepal is named after Nepa the cowherd, the founder of the Nepali scion of the Abhiras. In this account, the cow that issued milk to the spot where Nepa discovered the Jyotirlinga of Pashupatināth was also named Ne. The Korean interpretation also suggests a similar origin, where 'Ne' is a guardian spirit and 'pal' means protection, thus 'protection of God'.

The Ne Muni etymology was dismissed by early European visitors. Norwegian Indologist Christian Lassen proposed that Nepāla was a compound of Nipa (foot of a mountain) and -ala (short suffix for alaya meaning abode), so Nepāla meant "abode at the foot of the mountain". Indologist Sylvain Lévi found Lassen's theory untenable but suggested that either Newara is a vulgarism of Sanskrit Nepala, or Nepala is Sanskritisation of the local ethnic name; his view has found some support but does not fully answer the etymological question. It has also been proposed that Nepa is a Tibeto-Burman stem consisting of Ne (cattle) and Pa (keeper), reflecting that early inhabitants of the valley were Gopalas (cowherds) and Mahispalas (buffalo-herds). Suniti Kumar Chatterji believed Nepal originated from Tibeto-Burman roots - Ne, of uncertain meaning, and pala or bal, whose meaning is lost. Some scholars believe "Nepa:" referred to the Newar Kingdom. Another interpretation for "pal" is "gua" (cave), suggesting "holy cave."

Before the unification of Nepal, the Kathmandu Valley was known as Nepal. The entire territory controlled by the monarch seated in Kathmandu at any given time would also be referred to as Nepal.

Nepal's official name has undergone changes. Until August 2006, it was the Kingdom of Nepal. From August 2006 to August 2008, it was simply Nepal. From August 2008 to December 2020, it was the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal. Since December 14, 2020, the official name recognized by the United Nations is "Nepal". This change was initiated by the K.P. Sharma Oli cabinet, though it faced some domestic debate regarding its consistency with the 2015 constitution which refers to the "Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal".

3. History

This section chronicles the major historical events and development processes of Nepal from ancient times to the present, with a focus on their social impact, democratic development, and human rights. It covers early civilizations, various dynasties, the unification process, periods of autocratic rule, pro-democracy movements, and the establishment of the contemporary republic.

3.1. Ancient and Medieval Nepal

By 55,000 years ago, the first modern humans had arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa. The earliest known modern human remains in South Asia date to about 30,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence of human settlements in Nepal, specifically Paleolithic tools found in the Dumakhal area of Kathmandu Valley and the Terai region, dates to around the same time. Mesolithic and Neolithic tools have also been discovered in the Siwalik hills of Dang district.

The earliest inhabitants of modern Nepal and adjoining areas are believed to be people from the Indus Valley Civilisation. It is possible that Dravidian peoples inhabited the area before the arrival of Tibeto-Burmans and Indo-Aryans. By 4000 BC, Tibeto-Burmese people had reached Nepal. Stella Kramrisch (1964) mentions a substratum of pre-Dravidians and Dravidians in Nepal even before the Newars, who formed the majority of the ancient inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley.

Legends suggest that the Kathmandu Valley was once a lake, drained by Manjushri (Manjusri Bodhisattva) who cut open the surrounding mountains with a sword, making the land habitable.

By the late Vedic period, Nepal was mentioned in Hindu texts like the Atharvaveda Pariśiṣṭa and the Atharvashirsha Upanishad. The Gopal Bansa (Gopala dynasty) is mentioned as the earliest rulers of the central Himalayan kingdom known as 'Nepal'. They were followed by the Mahisapala dynasty and then the Kirata Kingdom, who ruled for over 16 centuries by some accounts. According to the Mahabharata, the then Kirata king participated in the Battle of Kurukshetra. In the south-eastern region, Janakpurdham was the capital of the prosperous kingdom of Videha or Mithila, home to King Janaka and his daughter, Sita.

Around 600 BC, small kingdoms and confederations of clans arose in the southern regions of Nepal. From one of these, the Shakya polity, arose a prince who later renounced his status, founded Buddhism, and came to be known as Gautama Buddha (traditionally dated 563-483 BC), born in Lumbini.

By 250 BC, the southern regions had come under the influence of the Maurya Empire. Emperor Ashoka made a pilgrimage to Lumbini and erected a pillar at Buddha's birthplace, the inscriptions on which mark a starting point for properly recorded history of Nepal. Ashoka also visited the Kathmandu valley and built monuments. By the 4th century AD, much of Nepal was under the influence of the Gupta Empire; Nepal is mentioned as a border country on Samudragupta's Allahabad Pillar.

In the Kathmandu valley, the Kiratas were pushed eastward by the Licchavis, and the Licchavi dynasty came into power around 400 AD. They built monuments and left a series of inscriptions, which are primary sources for this period's history. The Changu Narayan Temple, built in the 4th century AD, showcases fine Nepali woodcraft. Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang described Nepal in writings around 645 AD. In 641, Songtsen Gampo of the Tibetan Empire sent Narendradeva back to Licchavi with an army and subjugated parts of Nepal. The Licchavi dynasty declined in the late 8th century and was followed by a Thakuri rule. Thakuri kings, like Raghav Dev who started the Nepal Sambat in 869 AD, ruled until the middle of the 11th century AD, a period often called the dark period.

In the 11th century, a powerful empire of Khas people emerged in western Nepal, at its peak including much of western Nepal, parts of western Tibet, and Uttarakhand in India. By the 14th century, this Khasa Kingdom had splintered into the Baise rajya (22 states). The Khas language, later Nepali, became the lingua franca. In south-eastern Nepal, Simraungarh annexed Mithila around 1100 AD, and the unified Tirhut stood as a powerful kingdom for over 200 years, even ruling Kathmandu for a time. After 300 years of Muslim rule, Tirhut came under the control of the Sens of Makawanpur. In the eastern hills, a confederation of Kirat principalities ruled.

In the Kathmandu valley, the Mallas established themselves in Kathmandu and Patan by the mid-14th century. They ruled first under Tirhut's suzerainty but became independent by the late 14th century. Jayasthiti Malla introduced widespread socio-economic reforms, including a caste system modelled on the Hindu Varna system, which became an influential model for the Sanskritisation and Hinduisation of indigenous non-Hindu tribal populations. By the mid-15th century, Kathmandu was a powerful empire. In the late 15th century, Malla princes divided their kingdom into Kathmandu, Patan, Bhaktapur in the valley, and Banepa to the east. Competition among these kingdoms led to a flourishing of art and architecture, exemplified by the Durbar Squares of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur. However, their division and mistrust led to their fall in the late 18th century.

Apart from one destructive sacking of Kathmandu valley in the mid-14th century, Nepal remained largely untouched by the Muslim invasions of India. The Mughal period saw an influx of high-caste Hindus from India into Nepal. They intermingled with the Khas people, and by the 16th century, there were about 50 Rajput-ruled principalities, including the 22 Baisi states and 24 Chaubisi states. Gorkha, one of the Baisi states, emerged as an influential kingdom.

3.2. Unification and Kingdom of Nepal (Gorkha Dynasty)

In the mid-18th century, Prithvi Narayan Shah, a Gorkha king, set out to unify Nepal. He secured the neutrality of bordering mountain kingdoms and, after several bloody battles, notably the Battle of Kirtipur, conquered the Kathmandu Valley in 1769. The Gorkha control extended from the Kumaon and Garhwal Kingdoms in the west to Sikkim in the east. A dispute with Tibet over mountain passes and inner Tingri valleys led to the Sino-Nepalese War (1790-1791), compelling the Nepali forces to retreat and pay reparations to Qing China.

Rivalry with the British East India Company over control of states bordering Nepal led to the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-16). Initially underestimated, the British faced sound defeats until committing more resources. This war established the reputation of Gurkhas as fierce soldiers. The war ended with the Sugauli Treaty, under which Nepal ceded captured lands but retained its autonomy. The Madhesi people's land, who supported the East India Company, was returned to Nepal as a gift.

3.2.1. Rana Period

Factionalism within the royal family led to instability. In 1846, a plot by the reigning queen to overthrow Jung Bahadur Kunwar, a rising military leader, was discovered. This led to the Kot massacre, where armed clashes resulted in the execution of several hundred princes and chieftains. Bir Narsingh Kunwar emerged victorious, founding the Rana dynasty and becoming known as Jung Bahadur Rana. The king was made a titular figure, and the post of Prime Minister became powerful and hereditary.

The Ranas were staunchly pro-British, assisting them during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and in both World Wars. In 1860, some parts of the western Terai region (known as Naya Muluk) were gifted to Nepal by the British as a friendly gesture for its military help. In 1923, the United Kingdom and Nepal signed an agreement of friendship, superseding the Sugauli Treaty.

The Rana regime was characterized by tyranny, debauchery, economic exploitation, and religious persecution. The Hindu practice of Sati (widow self-immolation) was banned in 1919, and slavery was officially abolished in 1924. However, debt bondage, involving debtors' children, remained a persistent social problem, particularly in the western hills and the Terai. Despite these social issues, the Rana period saw a degree of modernization, including the establishment of the Nepal Cricket Association in 1946 by the Rana aristocracy, who had been educated in the British Empire.

3.3. Restoration of Monarchy and Pro-Democracy Movements

In the late 1940s, newly emerging pro-democracy movements and political parties in Nepal, such as the Nepali Congress (formed by Nepalis involved in the Indian independence movement) and the Communist Party of Nepal, became critical of the Rana autocracy. Following India's independence, and with India's support and the cooperation of King Tribhuvan (ruled 1911-1955), the Nepali Congress successfully overthrew the Rana regime in 1951, establishing a parliamentary democracy. This ended the Rana hegemony and restored the Shah monarchy to power.

After a decade of power wrangling between the king and the government, King Mahendra (ruled 1955-1972) scrapped the democratic experiment in 1960. He banned political parties, imprisoned or exiled politicians, and introduced a "partyless" Panchayat system to govern Nepal. While the Panchayat rule modernized the country to some extent, introducing reforms and developing infrastructure, it severely curtailed civil liberties and imposed heavy censorship. Hinduism was effectively made the state religion.

In 1990, the People's Movement (Jana Andolan I), a joint civil resistance launched by an alliance of political parties including the Nepali Congress and the United Left Front (a coalition of communist factions), forced King Birendra (ruled 1972-2001) to accept constitutional reforms and establish a multiparty democracy. A new constitution was promulgated in November 1990, enshrining popular sovereignty. The first multiparty general elections in 30 years were held in May 1991, with the Nepali Congress winning and Girija Prasad Koirala becoming Prime Minister. These movements significantly impacted social progress, advocating for civil liberties and the development of democratic institutions.

3.4. Establishment of the Republic and Contemporary Nepal

In 1996, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) started a violent insurgency, known as the Nepalese Civil War, aiming to replace the royal parliamentary system with a people's republic. This conflict resulted in more than 16,000 deaths. In January 2001, the Maoists formally established the People's Liberation Army.

The trajectory of Nepalese politics was dramatically altered by the Nepalese royal massacre on June 1, 2001. King Birendra, Queen Aishwarya, and seven other members of the royal family were killed. Crown Prince Dipendra was alleged to be the perpetrator, who then reportedly committed suicide. King Birendra's brother, Gyanendra, inherited the throne. Seeking to quash the Maoist insurgency, King Gyanendra dismissed the government in October 2002 and assumed direct rule, appointing Lokendra Bahadur Chand as prime minister. Public pressure forced him to reappoint Sher Bahadur Deuba as prime minister in June 2004. However, on February 1, 2005, King Gyanendra again dismissed the government and assumed full executive powers, declaring a state of emergency, effectively re-establishing absolute monarchy.

This move galvanized opposition. In December 2005, an alliance of seven parliamentary parties (Seven Party Alliance) and the Maoists agreed to work together against King Gyanendra's direct rule. The subsequent peaceful democratic revolution of 2006 (Loktantra Andolan or Jana Andolan II), characterized by widespread general strikes and protests, forced King Gyanendra to relinquish power and reinstate the dissolved House of Representatives on April 24, 2006. Girija Prasad Koirala's government was formed. On May 18, 2006, the reinstated parliament stripped the king of most of his powers, declared Nepal a secular state (ending its status as the world's only Hindu kingdom), and changed the national anthem. The Maoists entered mainstream politics following a comprehensive peace accord signed on November 21, 2006.

An interim constitution was promulgated on January 15, 2007. Elections for a Constituent Assembly were held on April 10, 2008, with the Maoists emerging as the largest party. On May 28, 2008, the first session of the Constituent Assembly formally declared Nepal a federal democratic republic, abolishing the 239-year-old monarchy. Ram Baran Yadav of the Nepali Congress was elected as the first President of Nepal in July 2008, and Pushpa Kamal Dahal (Prachanda) of the Maoist party became the first Prime Minister of the republic in August 2008.

The following years were marked by political instability and difficulty in drafting a new constitution. After two Constituent Assembly elections and several changes in government, the new Constitution of Nepal was promulgated on September 20, 2015. This constitution established Nepal as a federal democratic republic divided into seven provinces. However, the promulgation of the new constitution led to protests, particularly by Madhesi and Tharu communities in the Terai region, who felt marginalized by the new federal structure and demarcation of provinces, resulting in a blockade along the India-Nepal border that caused severe shortages of essential supplies.

Contemporary Nepal continues to grapple with challenges related to democratic consolidation, human rights (including issues faced by minorities like Madhesis and Dalits, and vulnerable groups), social justice, poverty, and economic development. The country is also focused on managing its relationships with its large neighbors, India and China, and addressing environmental concerns. Recent political developments include K. P. Sharma Oli becoming Prime Minister for the fourth time in July 2024, forming a coalition government between the Nepali Congress and UML, with a rotational premiership agreement until the next general elections in 2027.

4. Geography

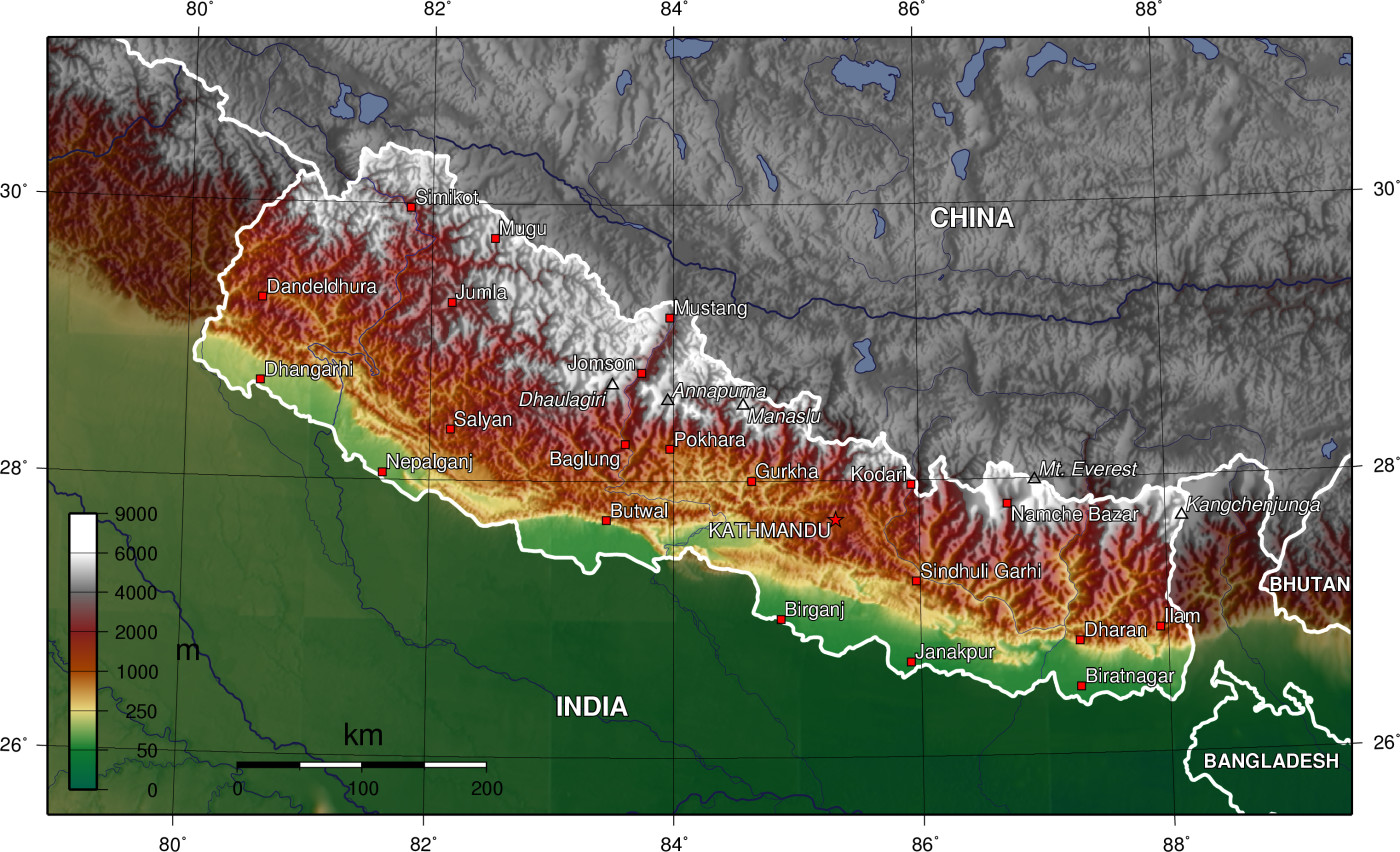

Nepal is roughly trapezoidal in shape, about 497 mile (800 km) long and 124 mile (200 km) wide, with an area of 57 K mile2 (147.52 K km2). It lies between latitudes 26° and 31°N, and longitudes 80° and 89°E. Nepal's defining geological processes began 75 million years ago when the Indian plate, then part of the southern supercontinent Gondwana, began a north-eastward drift. Simultaneously, the Tethyn oceanic crust to its northeast began to subduct under the Eurasian Plate. These dual processes created the Indian Ocean and caused the Indian continental crust eventually to under-thrust Eurasia and uplift the Himalayas. The rising barriers blocked river paths, creating large lakes, which only broke through as late as 100,000 years ago, forming fertile valleys like the Kathmandu Valley. In the western region, stronger rivers cut some of the world's deepest gorges. Immediately south of the emerging Himalayas, plate movement created a vast trough that rapidly filled with river-borne sediment, now constituting the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Nepal lies almost completely within this collision zone, occupying the central sector of the Himalayan arc, nearly one-third of the 1.5 K mile (2.40 K km)-long Himalayas, with a small strip of southernmost Nepal stretching into the Indo-Gangetic plain and two districts in the northwest stretching up to the Tibetan plateau.

Nepal is divided into three principal physiographic belts: Himal (mountains), Pahad (hills), and Terai (plains). The Himal is the mountain region containing snow, situated in the Great Himalayan Range; it makes up the northern part of Nepal. It contains the highest elevations in the world, including 29 K ft (8.85 K m) Mount Everest (Sagarmāthā in Nepali) on the border with China. Seven other of the world's "eight-thousanders" are in Nepal or on its border with Tibet: Lhotse, Makalu, Cho Oyu, Kangchenjunga, Dhaulagiri, Annapurna, and Manaslu. The Pahad is the mountain region that does not generally contain snow. The mountains vary from 2625 ft (800 m) to 13 K ft (4.00 K m) in altitude, with subtropical climates below 3.9 K ft (1.20 K m) to alpine climates above 12 K ft (3.60 K m). The Lower Himalayan Range, reaching 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) to 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m), is the southern limit of this region. Population density is high in valleys but notably less above 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m). The southern lowland plains or Terai bordering India are part of the northern rim of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, formed and fed by three major Himalayan rivers: the Koshi, the Narayani (Gandaki), and the Karnali. This region has a subtropical to tropical climate. The outermost range of foothills, the Sivalik Hills or Churia Range, crests at 2297 ft (700 m) to 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m). Inner Terai Valleys (Bhitri Tarai Upatyaka) lie north of these foothills.

The Indian plate continues to move north relative to Asia at about 2.0 in (50 mm) per year. This makes Nepal an earthquake-prone zone, and periodic earthquakes with devastating consequences present a significant hurdle to development. Erosion of the Himalayas is a very important source of sediment, which flows to the Indian Ocean. The Saptakoshi river, in particular, carries a huge amount of silt and is known as the "sorrow of Bihar" due to severe floods and course changes in India. Severe flooding and landslides cause deaths, disease, destroy farmlands, and cripple transport infrastructure during the monsoon season each year.

4.1. Climate

Nepal has five climatic zones, broadly corresponding to the altitudes.

- The tropical and subtropical zones lie below 3.9 K ft (1.20 K m).

- The temperate zone is from 3.9 K ft (1.20 K m) to 7.9 K ft (2.40 K m).

- The cold zone is from 7.9 K ft (2.40 K m) to 12 K ft (3.60 K m).

- The subarctic zone is from 12 K ft (3.60 K m) to 14 K ft (4.40 K m).

- The Arctic zone is above 14 K ft (4.40 K m).

Nepal experiences five seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn, winter, and spring. The Himalayas block cold winds from Central Asia in the winter and form the northern limits of the monsoon wind patterns, which bring significant rainfall, especially between June and September.

4.2. Biodiversity

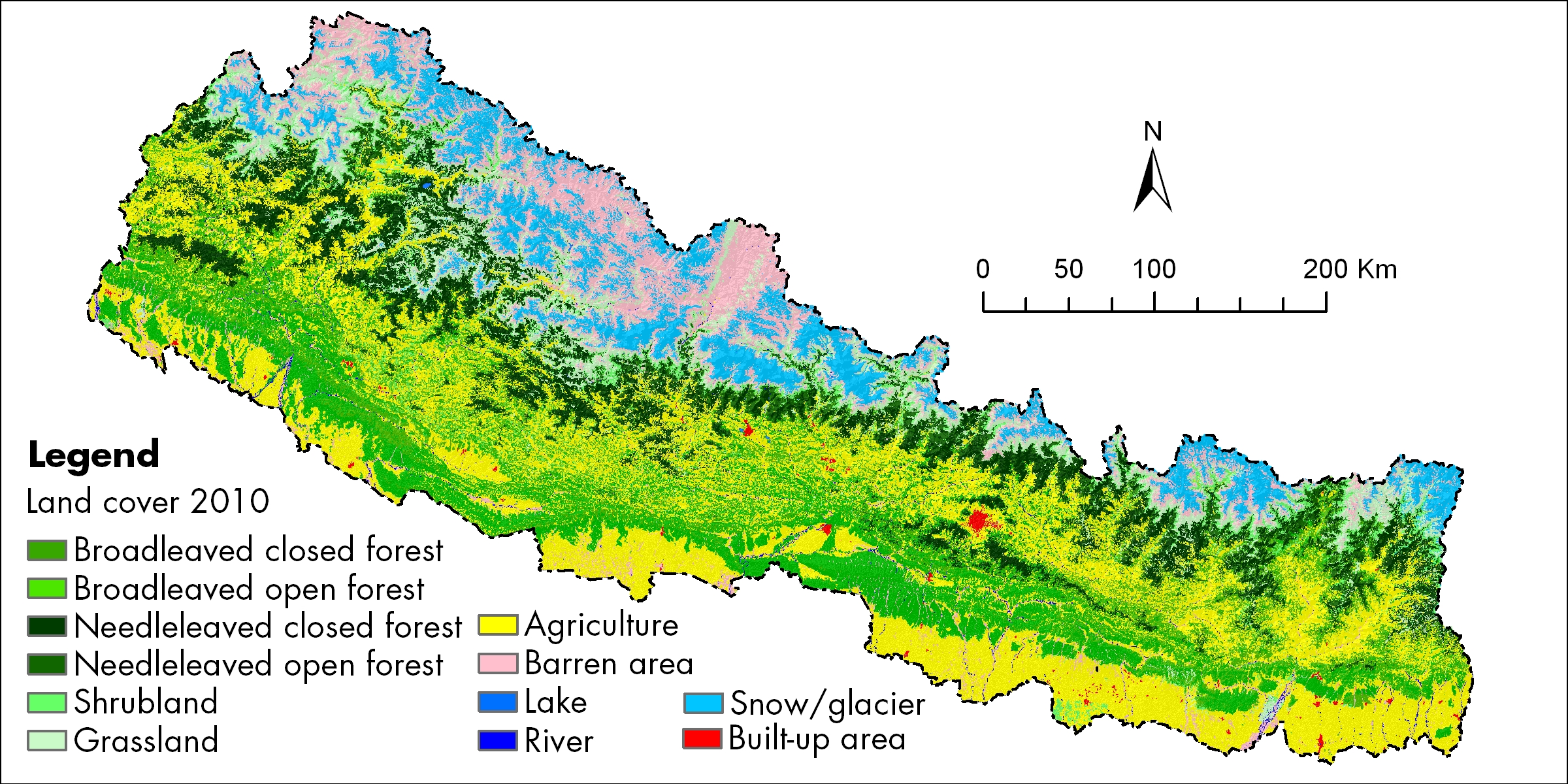

Nepal contains a disproportionately large diversity of plants and animals relative to its size. It forms the western portion of the Eastern Himalayan biodiversity hotspot, with notable biocultural diversity. The dramatic differences in elevation result in a variety of biomes. The eastern half of Nepal is richer in biodiversity as it receives more rain compared to western parts, where arctic desert-type conditions are more common at higher elevations. Nepal is a habitat for 4.0% of all mammal species, 8.9% of bird species, 1.0% of reptile species, 2.5% of amphibian species, 1.9% of fish species, 3.7% of butterfly species, 0.5% of moth species, and 0.4% of spider species. In its 35 forest types and 118 ecosystems, Nepal harbours 2% of flowering plant species, 3% of pteridophytes, and 6% of bryophytes.

Nepal's forest cover is 23 K mile2 (59.62 K km2), 40.36% of the country's total land area, with an additional 4.38% of scrubland, for a total forested area of 44.74%, an increase of 5% since the turn of the millennium. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.23/10, ranking it 45th globally out of 172 countries.

In the southern plains, the Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands ecoregion contains some of the world's tallest grasses as well as Sal (Shorea robusta) forests, tropical evergreen forests, and tropical riverine deciduous forests. In the lower hills (2297 ft (700 m) - 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m)), subtropical and temperate deciduous mixed forests containing mostly Sal (in lower altitudes), Chilaune (Schima wallichii) and Katus (Castanopsis indica), as well as subtropical pine forest dominated by chir pine, are common. The middle hills (6.6 K ft (2.00 K m) - 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m)) are dominated by oak and rhododendron. Subalpine coniferous forests cover the 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m) to 11 K ft (3.50 K m) range, dominated by oak, Eastern Himalayan fir, Himalayan pine, and Himalayan hemlock; rhododendron is common as well. Above 11 K ft (3.50 K m) in the west and 13 K ft (4.00 K m) in the east, coniferous trees give way to rhododendron-dominated alpine shrubs and meadows.

Notable trees include the astringent neem (Azadirachta indica), widely used in traditional herbal medicine, and the peepal (Ficus religiosa), displayed on ancient Mohenjo-daro seals and under which Gautama Buddha is said to have sought enlightenment.

Most of the subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest of the lower Himalayan region is descended from the Tethyan Tertiary flora. As the Indian Plate collided with Eurasia, the arid Mediterranean flora was pushed up and adapted to the alpine climate. The Himalayan biodiversity hotspot was a site of mass exchange of Indian and Eurasian species. One mammal species (Himalayan field mouse), two each of bird and reptile species, nine amphibian, eight fish, and 29 butterfly species are endemic to Nepal.

Nepal contains 107 IUCN-designated threatened species, including the endangered Bengal tiger, red panda, Asiatic elephant, Himalayan musk deer, wild water buffalo, and South Asian river dolphin, as well as the critically endangered gharial, Bengal florican, and white-rumped vulture. Human encroachment has critically endangered Nepali wildlife. In response, a system of national parks and protected areas was established in 1973 and substantially expanded. Nepal has ten national parks, three wildlife reserves, one hunting reserve, three conservation areas, and eleven buffer zones, covering 19.67% of the total land area. Ten wetlands are registered under the Ramsar Convention.

Conservation efforts, such as "vulture restaurants" and a ban on veterinary diclofenac, have seen a rise in white-rumped vultures. The community forestry programme, involving a third of the population in managing a quarter of forested areas, has helped local economies while reducing human-wildlife conflict. Breeding programmes and community-assisted military patrols have reduced poaching to near zero for some species, and their numbers have increased. However, Nepal consistently ranks among the most polluted countries globally. Air pollution, particularly in urban areas like Kathmandu, and trash accumulation, especially in tourist hotspots like Mount Everest, pose significant environmental and social challenges. River pollution, such as that of the Bagmati River, is also a major concern. Deforestation remains a challenge despite overall increases in forest cover, impacting local ecosystems and contributing to landslides and soil erosion, which disproportionately affect vulnerable communities.

5. Administrative Divisions

Nepal is a federal republic comprising 7 provinces. Each province is composed of 8 to 14 districts. The districts, in turn, comprise local units known as urban and rural municipalities. There is a total of 753 local units which includes 6 metropolitan municipalities, 11 sub-metropolitan municipalities and 276 municipalities for a total of 293 urban municipalities, and 460 rural municipalities. Each local unit is composed of wards, with 6,743 wards in total. The local governments enjoy executive and legislative as well as limited judicial powers in their local jurisdiction. The provinces have a unicameral parliamentary Westminster system of governance. The district coordination committee, composed of elected officials from local governments in the district, has a limited role. These administrative units are responsible for governance and service delivery at their respective levels.

| Province | Capital | Districts | Area | Population | Population | Density | Human Development Index (2019) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koshi Province | Biratnagar | 14 | 10 K mile2 (25.91 K km2) | 4,534,943 | 4,972,021 | 192 | 0.553 |  |

| Madhesh Province | Janakpur | 8 | 3.7 K mile2 (9.66 K km2) | 5,404,145 | 6,126,288 | 634 | 0.485 |  |

| Bagmati Province | Hetauda | 13 | 7.8 K mile2 (20.30 K km2) | 5,529,452 | 6,084,042 | 300 | 0.560 |  |

| Gandaki Province | Pokhara | 11 | 8.4 K mile2 (21.86 K km2) | 2,403,757 | 2,479,745 | 113 | 0.567 |  |

| Lumbini Province | Deukhuri | 12 | 7.6 K mile2 (19.71 K km2) | 4,499,272 | 5,124,225 | 260 | 0.519 |  |

| Karnali Province | Birendranagar | 10 | 12 K mile2 (30.21 K km2) | 1,570,418 | 1,694,889 | 56 | 0.469 |  |

| Sudurpashchim Province | Godawari | 9 | 7.5 K mile2 (19.54 K km2) | 2,552,517 | 2,711,270 | 139 | 0.478 |  |

| Nepal | Kathmandu | 77 | 57 K mile2 (147.18 K km2) | 26,494,504 | 29,192,480 | 198 | 0.579 |

5.1. Major Cities

Nepal's urban landscape is characterized by a few major cities that serve as economic, cultural, and administrative hubs. The capital, Kathmandu, located in the Kathmandu Valley, is the largest city with a population of 845,767 (2021 census). It is renowned for its rich history, ancient temples, and vibrant Newar culture. Challenges in Kathmandu include congestion, pollution, and drinking water shortages.

Pokhara, with a population of 518,452 (2021 census), is the second-largest city and a major tourist destination, known for its scenic Phewa Lake and proximity to the Annapurna mountain range. It is the capital of Gandaki Province.

Biratnagar, located in the Terai plains of Koshi Province, is an industrial city with a population of 244,750 (2021 census). It is a significant center for trade and commerce, particularly with India.

Bharatpur, in Bagmati Province, has a population of 369,377 (2021 census) and is a rapidly growing city and a major transportation hub.

Lalitpur (Patan), also in the Kathmandu Valley and part of Bagmati Province, has a population of 299,843 (2021 census). It is famous for its traditional arts, crafts, and historic Durbar Square.

Birgunj, in Madhesh Province, is a key entry point for trade with India and has a population of 268,273 (2021 census).

Other significant urban centers include Dhangadhi, Ghorahi, Itahari, Hetauda, Janakpur, Butwal, Tulsipur, Budhanilkantha, Dharan, Nepalgunj, Birendranagar, Tarakeshwar, Gokarneshwar, and Tilottama.

Urban development in these cities faces challenges related to unplanned growth, inadequate infrastructure, environmental degradation, and the need for improved social amenities and services to cater to their growing populations.

6. Politics and Government

Nepal is a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system, governed according to the Constitution of Nepal promulgated on September 20, 2015. This constitution defines Nepal as a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious, multi-cultural federal democratic republic committed to national independence, territorial integrity, and prosperity. The political system emphasizes democratic development, human rights, and social justice.

The country has seven national political parties recognized in the federal parliament as of recent elections: Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) (CPN-UML), Nepali Congress (NC), Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) (CPN-Maoist Centre), Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP), People's Socialist Party (PSP-N), and Janamat Party. The CPN (UML) is generally considered leftist, while the Nepali Congress is centrist; both officially espouse democratic socialism. After the 2022 Nepalese general election, a coalition government led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal (Prachanda) of the CPN (Maoist Centre) was formed. As of July 2024, K. P. Sharma Oli of CPN (UML) became Prime Minister for the fourth time, leading a new coalition with the Nepali Congress.

Political history since the 1950s has seen periods of democratic experimentation, monarchical rule (including the partyless Panchayat system), a decade-long civil war (1996-2006), and a transition to a republic in 2008. The political landscape has been shaped by pro-democracy movements, the Maoist insurgency, and ethnic nationalist movements, particularly the Madhes Movement.

6.1. Government Structure

The Government of Nepal is structured into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial, based on the principle of separation of powers.

The Executive branch is led by the President of Nepal, who is the ceremonial head of state and the supreme commander of the Nepalese Army. The President appoints the leader of the parliamentary party with a majority in the House of Representatives as the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is the head of government and forms the Council of Ministers (cabinet), which exercises executive power.

The Legislature of Nepal, known as the Federal Parliament, is bicameral. It consists of:

- The House of Representatives (Pratinidhi Sabha): The lower house, composed of 275 members. 165 members are elected through a first-past-the-post system from single-member constituencies, and 110 members are elected through a proportional representation system with political parties as the primary contestants. It has a term of five years.

- The National Assembly (Rashtriya Sabha): The upper house, consisting of 59 members. 56 members are elected by an electoral college comprising members of the provincial assemblies and heads/deputy heads of local units, with eight members from each of the seven provinces (including at least three women, one Dalit, and one person with a disability or from a minority group per province). Three members, including at least one woman, are nominated by the President on the recommendation of the Council of Ministers. The National Assembly is a permanent house, with one-third of its members elected every two years for a six-year term.

Provinces also have unicameral provincial assemblies.

6.2. Judiciary and Law Enforcement

Nepal has a unitary three-tier independent judiciary.

- The Supreme Court is the highest court, headed by the Chief Justice of Nepal. It has the power of judicial review and can issue various writs.

- High Courts: There are seven High Courts, one in each province, serving as the highest court at the provincial level.

- District Courts: There are 77 district courts, one in each district, serving as courts of first instance.

Municipal councils can convene local judicial bodies to resolve disputes and render non-binding verdicts in minor cases. The Constitution of Nepal is the supreme law, and any law inconsistent with it is void. Specific legal provisions are codified in the Civil Code and Criminal Code, along with procedural codes. The death penalty has been abolished. Marital rape is recognized, and abortion rights are supported, though constraints exist due to concerns about sex-selective abortion.

Primary law enforcement is the responsibility of the Nepal Police, an independent organization under the Ministry of Home Affairs, commanded by the Inspector General. It handles law and order and road traffic management (via Nepal Traffic Police). The Armed Police Force (APF) is a separate paramilitary organization that assists the Nepal Police in routine security, crowd control, counter-insurgency, anti-terrorism actions, and other internal security matters. The Central Investigation Bureau of Nepal Police specializes in criminal investigation. The Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) is an independent body that investigates corruption and abuse of authority.

Nepal's intentional homicide rate is relatively low. However, police data indicates a steady increase in the overall crime rate in recent years. Issues related to access to justice and human rights within the legal process remain, with concerns about delays in the justice system and the effective implementation of laws protecting vulnerable groups. Nepal was ranked 76th out of 163 countries in the Global Peace Index in 2019.

6.3. Human Rights and Social Issues

The status of human rights in Nepal is a complex issue, shaped by its history of political instability, civil conflict, and deep-rooted social hierarchies. The 2015 Constitution guarantees a range of fundamental rights, including equality, freedom, and social justice. However, challenges in implementation and persistent social issues affect the full realization of these rights.

Minority Rights: Ethnic minorities, particularly the Madhesi community in the Terai region and Dalits (formerly "untouchables"), continue to face discrimination and marginalization. Issues include underrepresentation in state institutions, lack of access to resources, and social exclusion. The Madhesi community has raised concerns about citizenship, political representation, and federal demarcation. Dalits, despite anti-discrimination laws, still suffer from caste-based discrimination, particularly in rural areas, affecting their access to education, employment, and public services.

Vulnerable Groups: Women, children, and persons with disabilities are among the vulnerable groups. Gender-based violence, including domestic violence and trafficking of women and girls, remains a serious problem. Child marriage, despite being illegal, is prevalent in some communities. Persons with disabilities face barriers in accessing education, healthcare, and employment.

LGBTQ+ Rights: Nepal has made significant strides in recognizing LGBTQ+ rights. The Supreme Court has issued progressive rulings, including the recognition of a third gender category in official documents and affirming the right to equality and non-discrimination. However, legal recognition of same-sex marriage is still pending, and social stigma persists.

Democratic Development and Social Justice: The transition to a federal democratic republic has been accompanied by challenges in democratic consolidation. Issues include political instability, corruption, and impunity for past human rights violations committed during the civil war. Access to justice can be difficult, particularly for marginalized communities.

Persistent Social Problems: Nepal grapples with various social problems such as poverty, illiteracy, and lack of access to adequate healthcare and sanitation, especially in remote areas. Witch-hunts, targeting predominantly women in rural communities, continue to be reported despite legal prohibitions. Bonded labor and child labor are also ongoing concerns.

Efforts to combat these issues include legislative reforms, affirmative action policies for marginalized groups, and programs run by governmental and non-governmental organizations. However, effective implementation and a change in societal attitudes are crucial for sustained progress in human rights and social justice.

7. Foreign Relations

Nepal maintains a foreign policy of non-alignment and neutrality, particularly between its two large neighbors, India and China. Amicable relations are sought with other countries in the region and globally. Nepal is a member of the United Nations (UN), South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), World Trade Organization (WTO), BIMSTEC, and the Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD), among others. Nepal hosts the permanent secretariat of SAARC in Kathmandu. The country has bilateral diplomatic relations with 167 countries and the EU, maintains embassies in 30 countries, and six consulates, while 25 countries have embassies in Nepal, and over 80 others maintain non-residential diplomatic missions.

Nepal is a major contributor to UN peacekeeping missions, having deployed over 119,000 personnel to 42 missions since 1958. Nepalese Gurkha soldiers have served in the Indian and British armies for over 200 years, participating in both World Wars and other conflicts, though Nepal itself was not directly involved.

7.1. Relations with India

Nepal and India share historically close political, economic, cultural, and religious ties. The 1950 Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship underpins this relationship. There is an open border between the two countries, allowing free movement of people. Nepalis can own property in India, and Indians are free to live and work in Nepal. India is Nepal's largest trading partner, and Nepal depends on India for all its oil and gas and many essential goods. However, relations have faced difficulties stemming from territorial disputes (such as over the Kalapani territory), border management, trade imbalances, water resources management, and perceived Indian influence in Nepalese internal affairs. The 2015 Nepal blockade, which Nepal attributed to India (though India denied official involvement), severely strained relations and highlighted Nepal's economic vulnerability. The impact of these issues on local communities living near the border and equitable sharing of resources remain sensitive topics.

7.2. Relations with China

Nepal and China established diplomatic relations on August 1, 1955, and signed a Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1960, based on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. Nepal maintains neutrality in conflicts between China and India and adheres firmly to the One-China policy, often curbing anti-China activities from the Tibetan refugee community within its borders. Citizens of both countries can cross the border and travel up to 19 mile (30 km) without a visa in designated areas. China is viewed favorably in Nepal due to the absence of major border disputes, its assistance in infrastructure development (such as the Araniko Highway), and aid during emergencies, particularly following the 2015 economic blockade by India. Subsequently, China granted Nepal access to its ports for third-country trade, and Nepal joined China's Belt and Road Initiative, which has geopolitical implications and diverse perspectives within Nepal.

7.3. Relations with South Korea

Diplomatic relations between Nepal and South Korea were established, leading to growing economic cooperation, cultural exchange, and people-to-people interactions. South Korea has become a significant destination for Nepalese migrant workers under the Employment Permit System (EPS). This labor migration contributes to Nepal's economy through remittances but also raises issues concerning workers' rights and welfare. Cultural exchanges include the popularity of Korean pop culture in Nepal and Nepalese cultural events in South Korea.

7.4. Relations with Other Countries

Nepal maintains diplomatic relations and cooperation with many other countries. Key aid donors include the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Denmark, and Norway. These countries have significantly influenced Nepal's development through financial and technical assistance in sectors like health, education, infrastructure, and democratic governance. Nepal's foreign policy aims to balance these relationships to support its sovereignty and development goals.

8. Military and Intelligence

The President of Nepal is the supreme commander of the Nepalese Army; its routine management is handled by the Ministry of Defence. The military expenditure for 2018 was approximately 398.50 M USD, around 1.4% of GDP. The Nepalese Army is an almost exclusively ground infantry force, with fewer than one hundred thousand personnel; recruitment is voluntary. It possesses a small air wing, the Nepalese Army Air Service, mainly comprising helicopters used for transport, patrol, and search and rescue.

The primary roles of the Nepalese Army include national defense, internal security, disaster relief, conservation of national parks (including anti-poaching patrols), and participation in United Nations peacekeeping missions. The army also undertakes major construction projects, particularly in remote areas.

Military intelligence is handled by the Directorate of Military Intelligence under the Nepalese Army. The National Investigation Department is an independent agency tasked with national and international intelligence gathering.

While there are no discriminatory policies on recruitment into the army, it has historically been dominated by men from elite Pahari warrior castes. Efforts are being made to make the armed forces more inclusive. The role of the military in a democratic society has been a subject of discussion, especially in the context of Nepal's transition from monarchy and civil conflict.

Nepal is also known for its Gurkha soldiers who serve in the British Army and the Indian Army, a tradition stemming from the Anglo-Nepalese War. Additionally, Nepalese individuals have been known to work for private military companies, such as Gurkha Security Guards, although Nepal is not a signatory to the Montreux Document on private military and security companies.

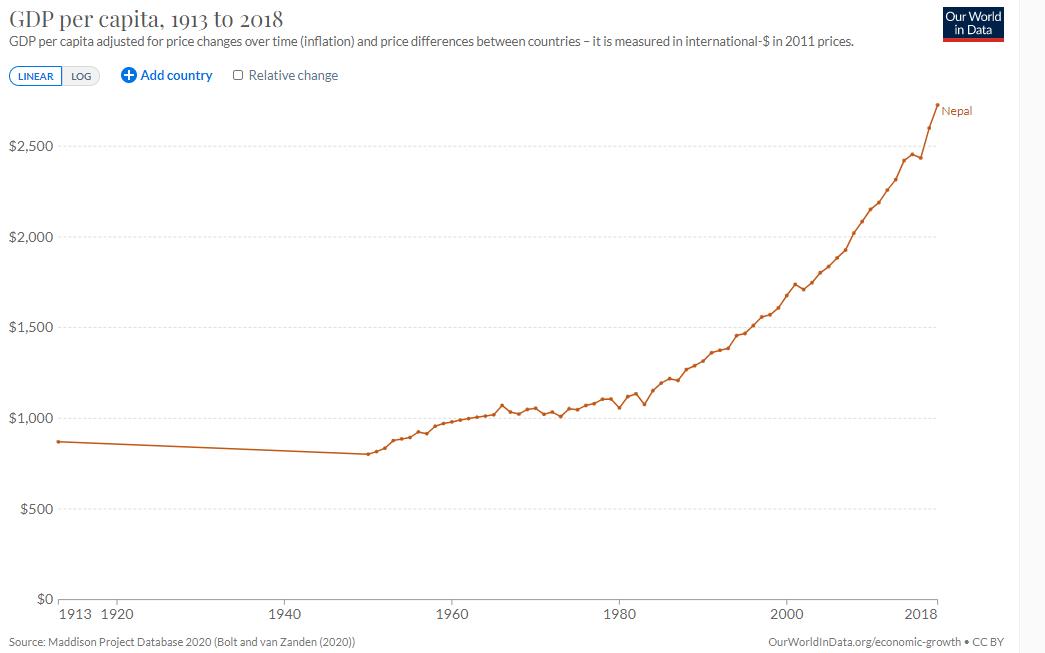

9. Economy

Nepal is one of the Least Developed Countries, ranking 165th in nominal GDP per capita and 162nd in GDP per capita at PPP as of 2019. Its GDP for 2019 was 34.19 B USD. Despite these figures, Nepal has made significant progress in poverty reduction, bringing the population below the international poverty line (US$1.90 per person per day) from 15% in 2010 to 9.3% in 2018, although vulnerability remains high. The economy faces challenges due to its landlocked geography, rugged terrain, limited natural resources, poor infrastructure, historical political instability, and the long-running civil war. Social equity, labor rights, and environmental sustainability are key considerations in its economic development. Nepal has been a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) since April 23, 2004.

9.1. Economic Structure

The Nepali labor force is the 37th largest in the world, with 16.8 million workers. The primary sector (mainly agriculture) contributes 27.59% to GDP, the secondary sector (industry) 14.6%, and the tertiary sector (services) 57.81%. Agriculture employs 76% of the workforce, services 18%, and manufacturing/craft-based industry 6%. Structural economic challenges include low productivity in agriculture, a narrow industrial base, and over-reliance on remittances.

9.2. Major Industries

Key sectors include:

- Agriculture: Main crops are cereals (barley, maize, millet, paddy, wheat), oilseed, potato, pulses, sugarcane, and jute. Dairy and water buffalo meat are also significant. The sector is vulnerable due to high dependence on monsoon rains, with only 28% of arable land irrigated (as of 2014). Labor rights in agriculture, particularly for landless laborers and women, and the environmental impact of farming practices are ongoing concerns.

- Tourism: A major industry, detailed further below.

- Textiles and Carpets: Important export earners, employing a significant number of people, particularly women. Issues include competition from other countries and the need for fair labor practices and environmentally sound production.

- Handicrafts: Diverse traditional crafts contribute to exports and local livelihoods. Equitable benefit sharing for artisans is a consideration.

Other industries include cigarette manufacturing, cement, brick production, and small-scale rice, jute, sugar, and oilseed mills.

9.3. Foreign Trade and Investment

Nepal's international trade expanded significantly after 1951. By FY 2016/17, foreign trade amounted to 1.06 T NPR. Over 60% of trade is with India.

- Major Exports: Readymade garments, carpets, pulses, handicrafts, leather, medicinal herbs, and paper products.

- Major Imports: Various finished and semi-finished goods, raw materials, machinery, equipment, chemical fertilizers, electrical/electronic devices, petroleum products, and gold.

Key export partners include the European Union (EU), the US, and Germany. Import partners include India, the United Arab Emirates, China, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) remains relatively low. Trade policies aim to promote exports and attract investment, but challenges include a large trade deficit and the need to ensure fair trade practices, protect economic sovereignty, and manage the social impact of international trade agreements. In 2022, Nepal limited imports of non-essential goods due to falling foreign currency reserves, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on tourism and remittances.

9.4. Tourism

Tourism is one of Nepal's largest and fastest-growing industries, employing over a million people and contributing 7.9% of the total GDP (as of 2018). International visitor arrivals crossed one million in 2018 for the first time (excluding Indian tourists arriving by land).

Key tourism segments include:

- Himalayan Mountaineering: Nepal is home to eight of the world's ten highest peaks, including Mount Everest, attracting mountaineers and trekkers globally. This is a significant source of revenue but also poses environmental challenges such as waste management on Everest and social impacts on local Sherpa communities.

- Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Kathmandu Valley, with its seven UNESCO World Heritage sites, and Lumbini, the birthplace of Buddha, are major attractions. Historic cities like Patan and Bhaktapur draw visitors with their ancient art and architecture.

- Adventure Tourism: Besides trekking and mountaineering, activities like white-water rafting, paragliding, and jungle safaris in national parks like Chitwan are popular.

Major tourist destinations include Pokhara (known for its lakes and mountain views), the Annapurna trekking circuit, Lumbini, Sagarmatha National Park, and Chitwan National Park.

Challenges for the tourism industry include infrastructure bottlenecks (especially transportation and high-end accommodation), issues with the national carrier Nepal Airlines, and the need for sustainable tourism practices to mitigate environmental degradation and ensure equitable benefits for local communities. Home-stay tourism, where tourists stay with local families, has seen some success in promoting cultural exchange and local economies. Overcrowding and pollution in popular areas like Everest base camp are growing concerns, necessitating better management and regulation.

9.5. Overseas Labor and Remittances

With high rates of unemployment and underemployment, millions of Nepalese seek employment abroad. Major destination countries include India, Gulf countries (Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE), Malaysia, and South Korea. In 2018, foreign exchange remittances amounted to 8.10 B USD, constituting 28.0% of GDP, ranking 19th globally.

Most overseas workers are unskilled or semi-skilled laborers. This sector faces significant social issues:

- Labor Rights and Exploitation: Many workers face exploitative conditions, including low wages (often below minimum wage), contract fraud by manpower agencies, confiscation of passports, unsafe working conditions, and long working hours. An average of two Nepalese migrant workers die abroad each day.

- Welfare of Migrant Families: While remittances help lift families out of poverty, the absence of (mostly male) workers can strain family structures and lead to social problems. The remittances are largely spent on real estate and consumption rather than entrepreneurial activities due to a lack of skills and support.

- Trafficking and Abuse: Women migrant workers, often facing restrictions, can become victims of traffickers and face violence and abuse.

The Nepalese government spends significant amounts on rescuing stranded workers, compensating families of deceased workers, and covering legal costs for those arrested abroad. International organizations and bilateral agreements (like the Employment Permit System with South Korea) aim to improve conditions, but challenges persist.

9.6. Poverty and Development Challenges

Nepal has made significant progress in poverty reduction, with the population below the international poverty line (US$1.90 per person per day) falling from 15% in 2010 to 9.3% in 2018. However, vulnerability remains high, with nearly 32% of the population living on between US$1.90 and US$3.20 per day. Income inequality is also a concern, with the highest 10% of households controlling 39.1% of national wealth and the lowest 10% controlling only 2.6%.

Key development challenges include:

- Geographical Constraints: Landlocked, rugged terrain, and susceptibility to natural disasters (earthquakes, floods, landslides) hinder development.

- Infrastructure Deficit: Inadequate transportation, energy, and communication infrastructure limits economic growth and access to services.

- Political Instability: A history of political turmoil has hampered consistent policy implementation and development efforts.

- Dependence on Agriculture: The agriculture sector is vulnerable to climate change and lacks modernization.

- Social Disparities: Caste-based discrimination, gender inequality, and regional disparities persist.

Government policies focus on sustainable and equitable development, including social welfare programs for vulnerable groups (such as scholarships for girls, disabled students, and children from marginalized communities), infrastructure development, and promoting sectors like tourism and hydropower. The government aims to graduate Nepal from Least Developed Country status. However, effective implementation of policies and addressing corruption are critical. Debt bondage, particularly in the Terai and western hills, remains a persistent social problem.

10. Infrastructure

Nepal's infrastructure development is crucial for its economic growth and social progress but faces significant challenges due to its rugged topography, limited resources, and historical political instability. Key sectors include energy, transportation, communications, and mass media, with an increasing focus on social accessibility and environmental considerations.

10.1. Energy

The bulk of energy in Nepal comes from biomass (80%) and imported fossil fuels (16%). Most final energy consumption is in the residential sector (84%), followed by transport (7%) and industry (6%). Nepal has no known oil, gas, or coal deposits (except some lignite) and imports all commercial fossil fuels, spending a significant portion of its export revenue. Only about 1% of energy needs are met by electricity.

Nepal has an estimated economically feasible hydropower potential of approximately 42,000 MW, but only around 1,100 MW has been exploited. Most generation is from run-of-river (ROR) plants, leading to power shortages in the dry winter months when peak demand can reach 1,200 MW, necessitating electricity imports of up to 650 MW from India. Major hydropower projects often suffer delays.

The national electrification rate was 76% (as of 2017), with disparity between urban (97%) and rural (72%) areas. Challenges in the power sector include high tariffs, system losses, generation costs, and lower domestic demand. There is a growing emphasis on sustainable energy solutions and ensuring equitable access for all communities, alongside mitigating the environmental impact of hydropower projects.

10.2. Transportation

Nepal remains isolated from major global transport routes. Aviation is relatively better, with 47 airports, 11 with paved runways; flights are frequent. Building roads and other infrastructure is difficult and expensive in the hilly and mountainous northern two-thirds of the country. As of 2016, Nepal had just over 7.4 K mile (11.89 K km) of paved roads, 10 K mile (16.10 K km) of unpaved roads, and only 37 mile (59 km) of railway line in the south. By 2018, all district headquarters (except Simikot) were connected to the road network. Most rural roads are not operable during the rainy season, and even national highways regularly become inoperable due to landslides and floods. Nepal depends heavily on aid from countries like China, India, and Japan for road construction and maintenance. The only practical seaport for goods bound for Kathmandu is Kolkata in India.

The poor road system makes access to markets, schools, and health clinics challenging, particularly for remote and marginalized communities. Nepal's road infrastructure is considered among the worst in Asia. The national carrier, Nepal Airlines, has faced mismanagement and corruption issues. China's Belt and Road Initiative includes plans for improved road and rail connectivity, such as a railway linking Tibet to Kathmandu.

10.3. Communications

According to the Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) MIS August 2019 report, the voice telephony subscription rate was 2.70% for fixed phones and 138.59% for mobile phones, with 98% of all voice telephony via mobile. An estimated 14.52% had access to fixed broadband, while an additional 52.71% accessed the internet using mobile data subscriptions, with nearly 15 million using 3G or better.

The mobile voice telephony and broadband market is dominated by the state-owned Nepal Telecom (55%) and the private multinational Ncell (40%). Nepal Telecom also holds a significant share (around 25%) of the fixed broadband market, with the rest served by private Internet Service Providers.

While there is a high disparity in penetration rates between rural and urban areas, mobile service has reached 75 districts, covering 90% of the land area. Broadband access is targeted to reach 90% of the population by 2020. Addressing the digital divide and ensuring affordable and reliable internet access, particularly in rural and remote areas, remains a key challenge for ICT development.

10.4. Mass Media

As of 2019, the state operates three television stations and national and regional radio stations. There are 117 private TV channels and 736 FM radio stations licensed for operation, including at least 314 community radio stations.

According to the 2011 census, 50.82% of households possessed a radio, 36.45% a television, 19.33% cable TV, and 7.28% a computer. As of 2017, of the 833 publications producing original content, ten national dailies and weeklies were rated A+ class by the Press Council Nepal.

Press freedom in Nepal has seen improvements since the end of the monarchy and civil war, but challenges remain. Journalists occasionally face threats and harassment, and self-censorship can occur. In 2019, Reporters Without Borders ranked Nepal 106th in the world in terms of press freedom. The media plays an important role in democratic discourse, public awareness, and holding power accountable. The growth of online media has expanded the information landscape but also brought challenges related to misinformation and regulation.

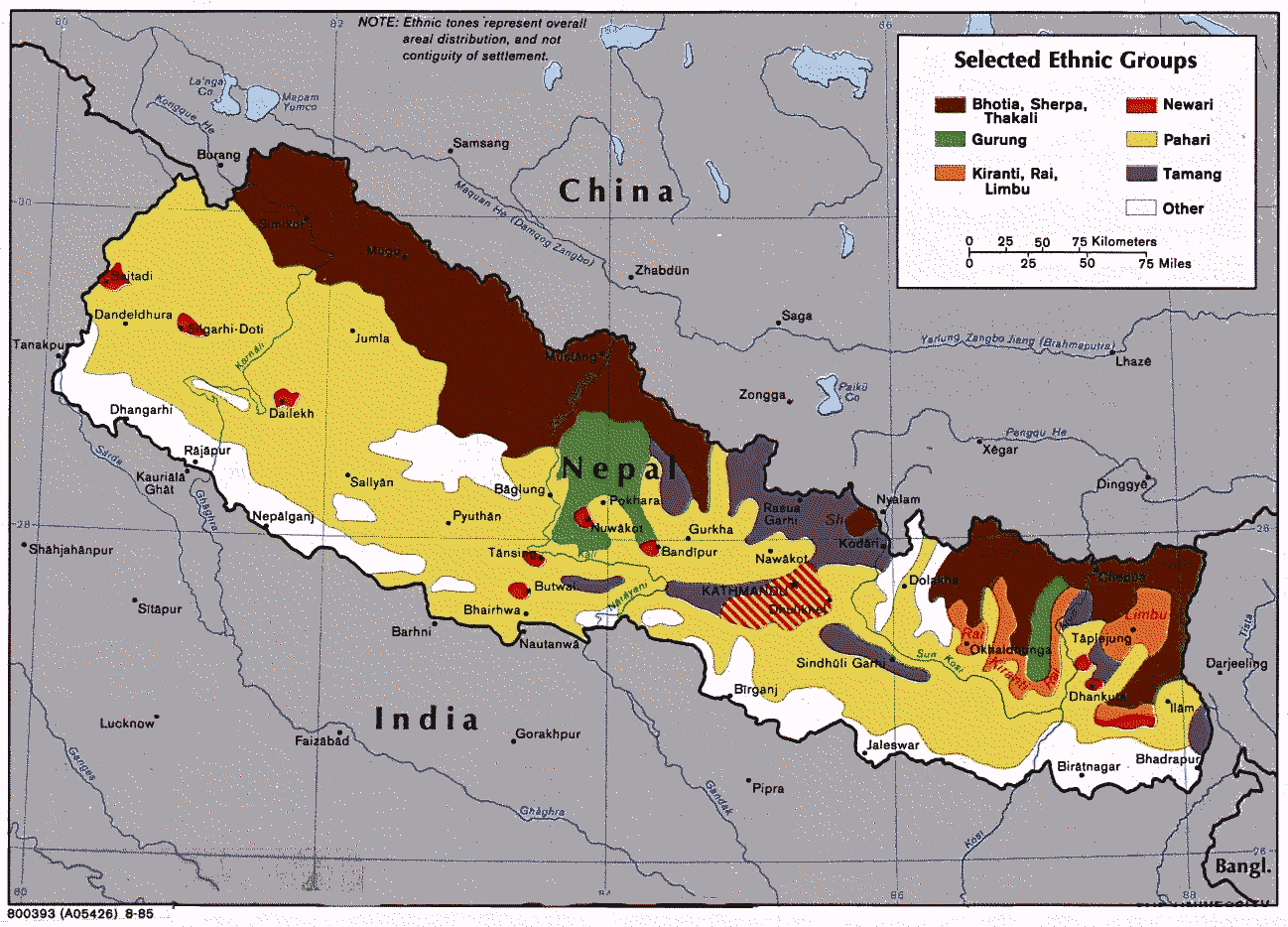

11. Demographics

The citizens of Nepal are known as Nepali or Nepalese. They are descendants of three major migrations from India, Tibet, and North Burma/Yunnan (via Assam). Early inhabitants included the Kirat of the eastern region, Newars of the Kathmandu Valley, aboriginal Tharus of the Terai plains, and Khas Pahari people of the far-western hills.

Nepal's population was 26.5 million according to the 2011 census, almost a threefold increase from nine million in 1950. By the 2021 census, the population reached 29,192,480. From 2001 to 2011, the average family size declined from 5.44 to 4.9. The 2011 census noted some 1.9 million absentee people (mostly male laborers employed overseas), contributing to a drop in the sex ratio to 94.2 (from 99.8 in 2001). The annual population growth rate was 1.35% between 2001 and 2011.

Nepal is one of the ten least urbanized but ten fastest urbanizing countries. As of 2014, an estimated 18.3% of the population lived in urban areas. Urbanization is high in the Terai, doon valleys, and middle hill valleys, but low in the high Himalayas. The capital, Kathmandu, is the largest city. Congestion, pollution, and drinking water shortages are major problems in rapidly growing cities, especially the Kathmandu Valley.

The age distribution shows a youthful population, with 38% under 14 years, 58.2% between 15-64 years, and 3.8% aged 65 and above (2008 estimate). The median age was 20.7 years (2008 estimate). Social implications of these demographic trends include pressure on education, employment, and healthcare services, as well as challenges related to rapid urbanization and managing a large youth population.

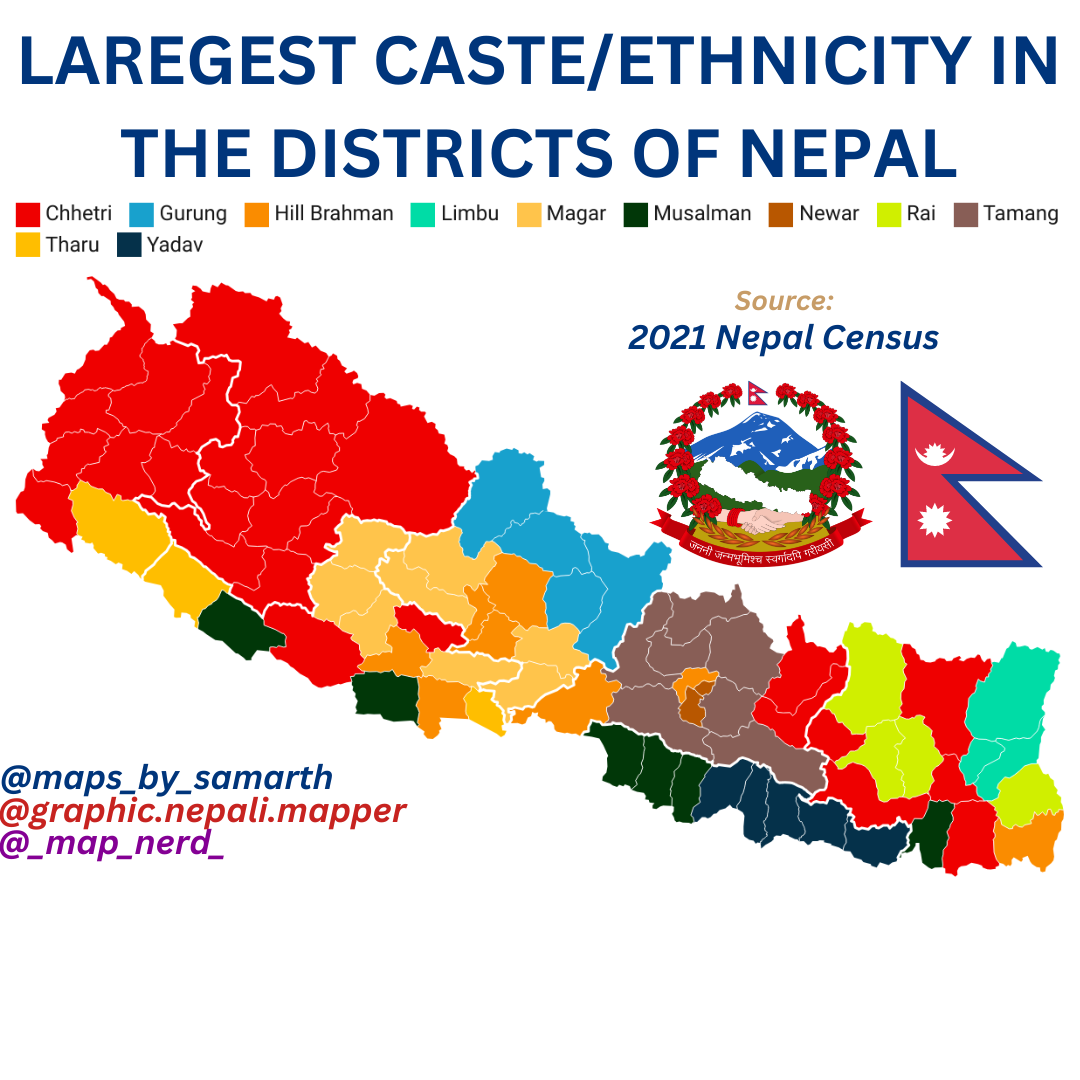

11.1. Ethnic Groups and Caste System

Nepal is a multicultural and multiethnic country, home to 125 distinct ethnic groups. The largest ethnic groups/castes according to the 2011 census are Chhetri (16.6%), Hill Brahmin (12.2%), Magar (7.1%), Tharu (6.6%), Tamang (5.8%), Newar (5.0%), Kami (4.8%), Muslim (4.4%), Yadav (4.0%), and Rai (2.3%). Other groups like Gurung, Damai, Thakuri, Limbu, and Sarki also form significant parts of the population. These groups have distinct cultural characteristics and are distributed across Nepal's diverse geography.

The Nepali caste system historically defined social stratification. While untouchability was declared illegal in 1963 and other anti-discriminatory laws have been enacted, caste-based discrimination, particularly against Dalit communities (such as Kami, Damai, Sarki), persists, especially in rural areas. This discrimination impacts access to resources, education, employment, and social justice. The government has implemented affirmative action policies and social welfare initiatives to promote social inclusion and address the issues faced by marginalized communities, but deep-rooted societal attitudes and practices remain a challenge. The complex interplay of ethnicity and caste continues to influence social and political dynamics in Nepal.

11.2. Languages

Nepal's diverse linguistic heritage stems from three major language groups: Indo-Aryan, Sino-Tibetan, and various indigenous language isolates. The 2011 census listed 123 languages spoken as mother tongues.

The official language is Nepali, an Indo-Aryan language written in Devanagari script. It is spoken as a mother tongue by 44.6% of the population and serves as the lingua franca among different ethnolinguistic groups.

Major minority languages include:

- Maithili (11.7%)

- Bhojpuri (6.0%)

- Tharu (5.8%)

- Tamang (5.1%)

- Nepal Bhasa (Newar) (3.2%)

- Bajjika (3.0%)

- Magar (3.0%)

- Doteli (3.0%)

- Urdu (2.6%), common among Nepali Muslims

- Awadhi (1.89%)

Other languages like Sunwar, Limbu, Gurung, and varieties of Tibetan are also spoken. Standard literary Tibetan is understood by those with religious education in the higher Himalayan regions.

Language policies in Nepal aim to promote and preserve linguistic diversity. The constitution recognizes all mother tongues spoken in Nepal as national languages. There are efforts to develop writing systems for many unwritten local dialects. Access to information and education in mother tongues for linguistic minorities remains a challenge, impacting cultural identity and equitable participation in society. Nepal is also home to at least four indigenous sign languages.

11.3. Religion

Nepal was declared a secular country by the Interim Constitution of 2007, a status reaffirmed in the 2015 Constitution. The constitution protects religious and cultural freedom, including the protection of religion and culture handed down from ancient times (Sanatan).

The religious composition according to the 2011 census was:

- Hinduism: 81.3%

- Buddhism: 9.0%

- Islam: 4.4%

- Kirant (indigenous animistic religion of Kirati ethnic groups): 3.1%

- Christianity: 1.4%

- Prakriti (nature worship) or other folk religions: 0.5%

- Bon (Tibetan indigenous faith) and others constituted the remainder.

Nepal has the largest percentage of Hindus in the world. Historically, it was the world's only Hindu kingdom, with Shiva considered the guardian deity. There is a significant degree of syncretism between Hinduism and Buddhism, with many Nepalese practicing elements of both. Sacred sites are often shared, and deities are mutually respected.

Religious tolerance and harmony generally prevail, though isolated incidents of religiously motivated tension or violence have occurred. The constitution prohibits proselytization or converting any person from one religion to another. An anti-conversion law was passed in 2017, which has raised concerns among minority religious groups, particularly Christians, regarding its potential impact on religious freedom and charitable activities. The state aims to protect the rights of minority religious groups and ensure freedom of religion and worship, but challenges related to social discrimination and the interpretation of secularism persist.

11.4. Education

Nepal entered modernity in 1951 with a literacy rate of 5% and about 10,000 students enrolled in 300 schools. By 2017, there were over seven million students enrolled in 35,601 schools. The overall literacy rate (for population age five years and above) increased from 54.1% in 2001 to 65.9% in 2011. The net primary enrolment rate reached 97% by 2017. However, enrolment was less than 60% at the secondary level (grades 9-12) and around 12% at the tertiary level. While there is significant gender disparity in the overall literacy rate (men 75.1%, women 57.4% in 2011), girls have overtaken boys in enrolment at all levels of education.

Nepal has eleven universities, including Tribhuvan University (the oldest and largest) and Kathmandu University, and four independent science academies.

Challenges in the educational environment include:

- Access and Equity: Disparities persist between urban and rural areas, and among different social groups (caste, ethnicity, gender, disability). Ensuring access to quality education for children from marginalized communities remains a priority.

- Quality: Issues include a lack of proper infrastructure, teaching materials, a high student-to-teacher ratio, and the need for improved teacher training and curriculum development.

- Politicization: Politicization of school management committees and partisan unionization among students and teachers can hinder progress.

Free basic education is guaranteed in the constitution, but the program often lacks adequate funding for effective implementation. The government has scholarship programs for girls, disabled students, children of martyrs, marginalized communities, and the poor. Tens of thousands of Nepali students leave the country annually for better education and work opportunities, with a significant portion not returning, contributing to a "brain drain". Nepal was ranked 109th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

11.5. Health

Healthcare services in Nepal are provided by both public and private sectors. Life expectancy at birth was estimated at 71 years as of 2017 (153rd highest globally), a significant improvement from 54 years in the 1990s and 35 years in 1950. Two-thirds of all deaths are due to non-communicable diseases, with heart disease being the leading cause. Sedentary lifestyles, imbalanced diets, and consumption of tobacco and alcohol contribute to this rise. However, many also die from communicable and treatable diseases due to poor sanitation, malnutrition, and lack of awareness and access to healthcare, particularly in rural areas.

Nepal has made great progress in maternal and child health. 95% of children have access to iodized salt, and 86% of children aged 6-59 months receive Vitamin A prophylaxis. Stunting, underweight, and wasting among children have been significantly reduced, though malnutrition remains high (43% among children under five). Anemia in women and children increased between 2011 and 2016. Low birth weight is at 27%, while breastfeeding is at 65%. The maternal mortality rate was reduced to 229 per 100,000 live births (from 901 in 1990), and infant mortality is down to 32.2 per thousand live births (from 139.8 in 1990). Contraceptive prevalence rate is 53%, but rural-urban disparity is high.

Public health centers provide 72 essential medicines free of cost. A public health insurance plan initiated in 2016, covering treatments up to 50.00 K NPR for five family members for a premium of 2.50 K NPR per year, has seen limited success but is expanding. Stipends for antenatal visits and hospital deliveries decreased home-births from 81% in 2006 to 41% in 2016. School meal programs have improved education and nutrition metrics. The "one household-one toilet" program saw toilet prevalence reach 99% in 2019 (from 6% in 1990).

Challenges include ensuring accessibility and affordability of healthcare for all, particularly in remote regions, improving the quality of services, addressing health equity, and tackling public health issues like sanitation and infectious diseases.

11.6. Migrants and Refugees

Nepal has a long tradition of accepting immigrants and refugees. In modern times, Tibetans and Bhutanese have constituted the majority of refugees.

- Tibetan Refugees: Began arriving in 1959 after the Chinese takeover of Tibet. Many more continue to cross into Nepal annually, often en route to India. The Tibetan refugee community faces challenges related to legal status, freedom of movement, and employment, with increasing pressure from China on Nepal to curb their activities.

- Bhutanese Refugees: Lhotshampa (ethnic Nepalis from Bhutan) refugees began arriving in the 1980s, and their numbers exceeded 110,000 by the 2000s, following their expulsion from Bhutan. Most have been resettled in third countries (e.g., USA, Canada, Australia, European nations) through UNHCR programs.

As of late 2018, Nepal had a total of 20,800 confirmed refugees, 64% Tibetan and 31% Bhutanese. Economic immigrants and refugees fleeing persecution or war from neighboring countries, Africa, and the Middle East, often termed "urban refugees" (living in cities instead of camps), lack official recognition, but the government facilitates their resettlement in third countries.

Approximately 2,000 immigrants, half of them Chinese, applied for work permits in 2018/19. The government lacks data on Indian immigrants, as they do not require permits to live and work in Nepal due to the open border treaty. The Government of India estimated 600,000 Non-Resident Indians in Nepal as of 2018.

The presence of migrants and refugees raises issues of human rights, welfare, social integration, access to services, and the impact on host communities and national resources.

12. Culture

Nepalese culture is a rich tapestry woven from the traditions of its diverse ethnic groups, languages, and religions. It reflects a blend of influences from India to the south and Tibet/China to the north, while maintaining its unique Himalayan character. Traditional social structures, customs, arts, cuisine, and sports highlight its diversity and dynamism.

12.1. Society and Customs

Traditional Nepali society is often defined by social hierarchy, with the Nepali caste system historically embodying social stratification and restrictions. Social classes are defined by over a hundred endogamous hereditary groups (jātis or castes). Although untouchability was declared illegal in 1963 and anti-discriminatory laws have been enacted, caste-based discrimination, particularly against Dalits, persists, impacting their social and economic opportunities. In urban settings, caste-related identification has lessened in importance in workplaces and educational institutions.

Family values are paramount, and multi-generational patriarchal joint families have been the norm, though nuclear families are increasingly common in urban areas. Arranged marriages are prevalent, often with parental consent being a significant factor. Marriage is generally considered a lifelong commitment, and divorce rates are extremely low. Child marriage, especially in rural areas, remains a concern despite being illegal.

Many Nepali festivals are religious in origin. Prominent festivals include Dashain (a 15-day Hindu festival celebrating the victory of good over evil), Tihar (festival of lights, honoring Laxmi, crows, dogs, cows, and brothers), Teej (a festival for women), Chhath (worship of the sun god), Maghe Sankranti (marking the end of winter), Sakela (celebrated by Kirati communities), Holi (festival of colors), and the Nepali New Year (Vikram Samvat). The Gadhimai festival, held every five years, has historically involved large-scale animal sacrifice, drawing criticism from animal welfare activists, though efforts have been made to curb this practice. Animal sacrifices also occur during Dashain, which has also raised concerns about animal cruelty.

A challenging social issue is the persistence of witch-hunt accusations, primarily targeting vulnerable women (elderly, widows, lower-caste) in rural areas. Victims often face severe torture, public humiliation, and sometimes death. Despite laws against such practices, enforcement and social reform efforts are ongoing.

12.2. National Symbols

The Emblem of Nepal depicts the snowy Himalayas, forested hills, and fertile Terai, supported by a wreath of rhododendrons (the national flower). The national flag is at the crest, with a plain white map of Nepal below it. A man's and woman's right hands are joined to signify gender equality. At the bottom is the national motto in Sanskrit, written in Devanagari script: जननी जन्मभूमिश्च स्वर्गादपि गरीयसीJanani Janmabhūmisca Svargādapi garīyasiSanskrit ("Mother and Motherland are greater than Heaven").

- National Flag: The world's only non-rectangular national flag, consisting of two stacked triangular pennants. The crimson red is the color of the rhododendron and symbolizes victory or courage. The blue border signifies peace. The upper pennant bears a white crescent moon and star, and the lower pennant a white sun, representing permanence and the hope that Nepal will last as long as the sun and moon.

- National Anthem: "Sayaun Thunga Phulka" (Made of Hundreds of Flowers).

- National Animal: Cow.

- National Bird: Himalayan monal (डाँफेDanpheNepali).

- National Flower: Rhododendron (लाली गुराँसLali GuransNepali).

- National Dress: Daura-Suruwal for men and Gunyu-Cholo for women (though no longer officially mandated to avoid favoritism, they are widely recognized).

- National Sport: Volleyball (declared in 2017).

- National Color: Crimson.

The President is the symbol of national unity. Martyrs of Nepal are symbols of patriotism. Figures like Prithvi Narayan Shah are considered foundational.

12.3. Art and Architecture

The oldest known examples of architecture in Nepal are stupas from early Buddhist constructions around Kapilvastu and those built by Emperor Ashoka in the Kathmandu Valley (circa 250 BC). The characteristic Newar architecture, developed and refined by artisans of the Kathmandu Valley since at least the Licchavi period, is renowned. This style prominently features wood, with intricate carvings of geometrical patterns, deities, and mythical beings.

Key architectural styles include:

- Pagoda temples: Typically multi-roofed structures built with wood, often featuring clay or gold-plated tiles. Roofs diminish in proportion successively, topped by a golden finial. Bases are usually rectangular terraces of carved stone. The Changu Narayan Temple (4th century AD) is an early example. The Nyatapola Temple in Bhaktapur is a famous five-storied pagoda.

- Stupas: Hemispherical structures, important in Buddhist architecture, such as Swayambhunath and Boudhanath in Kathmandu.

- Shikhara style temples: Common in Hindu architecture, influenced by Indian styles.

The Durbar Squares of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur are UNESCO World Heritage sites showcasing the culmination of Nepali wood, metal, and stone craftsmanship. Bronze and copper work is evident in deity sculptures, decorative elements, and everyday items. The "ankhijhyal" (peacock window) is a unique example of Nepali woodcraft.

Thanka (or Paubha) painting is a traditional Tibetan Buddhist art form practiced in Nepal by Buddhist monks and Newar artisans.

Cultural Heritage Preservation: Nepal faces significant challenges in preserving its cultural heritage, including damage from earthquakes (like the 2015 earthquake) and the looting and illicit trafficking of artifacts. Efforts are underway for restoration, conservation, and the repatriation of stolen artifacts from museums and private collections abroad, with volunteer groups like the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign playing an active role. Several successful repatriations have occurred from institutions in the US and UK.

12.4. Literature and Performing Arts

Nepal's literature was intertwined with that of South Asia until its unification. Early works were often religious texts in Sanskrit. Nepali language literature dates back to the 13th century, but significant works older than the 17th century are rare. Newar literature has a history of almost 500 years.

The modern era of Nepali literature began with Bhanubhakta Acharya (1814-1868), who composed influential works in Nepali, notably the Bhanubhakta Ramayana. Motiram Bhatta further popularized Nepali literature in the late 19th century. By the mid-20th century, Nepali literature began addressing contemporary social problems, influenced by Western traditions. After the advent of democracy in 1951, literature in Nepali and other national languages flourished. Post-civil war experiences and global literary trends have strongly influenced recent Nepali literature.

Traditional Music and Dance: Nepal has a rich tradition of folk music and dance, varying by ethnic group and region. Some examples from hilly regions include Maruni, Lakhey, Sakela, Kauda, and Tamang Selo. Instruments like the Nepali sarangi (a stringed instrument) are common.